The Channel Tunnel has now been around for long enough that to many it seems almost unremarkable. Certainly for me it does – it’s been in existence longer than I have, and it’s something I take for granted.

The idea of a tunnel linking Britain and France was published as early as 1802 and probably dreamt of long before that.

From there, it’s a long and stuttered history. A formal proposal was agreed in 1874, fell through, and another made in 1929 but rejected as too costly, before another agreement was made in 1964. Studies then took place before the construction proper started in 1974. Less than a year later, the new Labour Government cancelled the project.

The new Conservative Government rejuvenated the idea in 1979 and the Channel Tunnel Group was founded in 1985. Construction began again in 1988.

The tunnel opened in 1994. It had cost £4.650 billion, or around £13bn today (80% over budget).

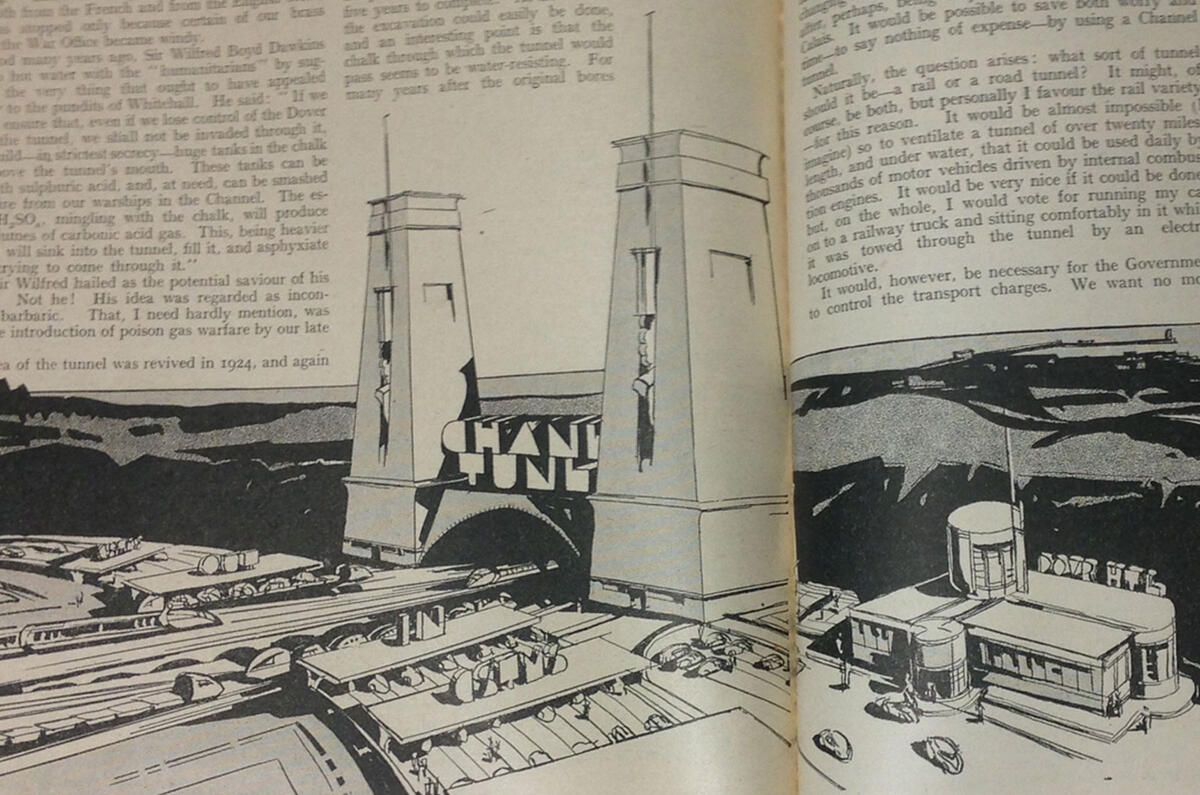

Back on 9 August 1935, Autocar argued the case for the tunnel.

“What a good thing it would be if police doctors were to abandon the time-honoured ‘British Constitution’ as a test of sobriety and substitute the words ‘Channel Tunnel’,” we began.

“The point is that to adopt the phrase would be to accustom the more hilarious members of the community – and through them the public at large – to the great notion of burrowing to France.”

We then laid out a short history of the tunnel idea: “The project was approved in principle, on both sides of the channel, in 1874. Indeed, boring actually began about that time both from the French and from the English coast, and was stopped only because certain of our brass hats at the War Office became windy.”

In fact, such was the attitude of the time that during the 1880s, one Sir Wilfred Boyd Dawkins had an ‘inconceivably barbaric’ idea, in his words: “If we want to ensure that, even if we lose control of the Dover end of the tunnel, we shall not be invaded through it, let us build – in strictest secrecy – huge tanks in the chalk cliffs above the tunnel’s mouth. These tanks can be filled with sulphuric acid, and, at need, can be smashed by gunfire from our warships in the Channel. The escaping H2SO4 mingling with the chalk, will produce huge volumes of carbonic acid gas. This, being heavier than air, will sink into the tunnel, fill it, and asphyxiate anyone trying to come through it.”

Interesting…

Throwback Thursday: "I want a one-man car", 1942

On the 1924 efforts, we described: “Our legislators turned it down with a bump; indeed, they seemed to regard it as a rather indifferent jest.”

We then proceeded to analyse the feasibility of a tunnel under la Manche.

“From the engineering point of view the problem appears simple enough. The boring, as compared with what has been done through hard rock, would be child’s play, for the ‘subsoil’ of the Channel’s bed is soft.”

Apparently, the estimate of five years for the tunnelling work had been made – although one American study claimed one month was possible! In reality, the French and English tunnelling teams met in the middle of the tunnel in 1990, two years after boring began.

So, construction was possible in theory, but did Autocar of 1935 think such a tunnel would be a financial success?

“There would be no fear of it not paying,” we confidently stated.

“Quite stiff tolls could be implemented, because exporters of goods could save several costly handlings [by using the tunnel].”

Freight certainly has been a successful business for the tunnel – in its first year, 800,000 tonnes of freight passed through, and last year the figure was 20,720,000 tonnes.

We also foresaw what system would be used for cars: “It would be almost impossible to ventilate a tunnel of over 20 miles in length. I would vote for running my car onto a railway truck and sitting comfortably in it while it was towed through the tunnel by an electric locomotive.”

Interestingly, Autocar was prophetic about closer political relations with l’Hexagone, too: “If the French knew us better they might not be so suspicious of our motives; and if our people knew them better we should be more tolerant of their little eccentricities. A tunnel might be the flux to weld the two countries into a closer union.”

We concluded by noting that in 1929 an Autocar reader had suggested a 200-feet-high bridge across the Channel, and in 1928 two jetties with a canal for ferries in between and a viaduct at each end to allow shipping to pass underneath, both of which seemed just as feasible as a tunnel.

“There is every reason to think that in due course some scheme will be adopted to simplify the cross-Channel passage. The question is: What Government will have the foresight to get busy with it?”

Add your comment