The year is 2035. You’re driving a brand new electric car and you glide into a nearby forecourt. What does it look like? If it’s a large chain establishment, you can expect to be greeted by a fleet of chargers, a small supermarket store and a large car park. But if it’s a smaller, independent forecourt, especially in a rural area, the scene will be different. In fact, it might not exist at all.

At first bite, this sounds melodramatic. Historically, petrol stations have been struggling for several years. From a peak of around 35,000 in 1980, there are now just over 8000, according to the latest figures from the Petrol Retailers Association (PRA).

The pandemic directly caused around 100 stations to pause sales last year. As of 2019, 70% of independent filling stations that were operating in 2000 have shut their doors permanently.

But according to Gordon Balmer, the commercial manager for the PRA, many of those forecourts that survived the pandemic have not just survived but thrived. “Before the pandemic, the cumulative average growth rate [for convenience retail] was about 4% year on year,” he says. “The pandemic has actually accelerated it: it went up last year to around 6%.”

Lockdown rules forced consumers to shop more locally, and with more and more forecourts now offering what Balmer describes as “world class” food and retail facilities – including one Scottish station that even offers a cigar tasting service – the pandemic created something of a perfect storm.

“We’re a world away from mouldy sausage rolls,” Balmer says. “When people have gone to their fuel station to buy food, they’ve found that they’ve not only got what they want, but they’ve got it at a good price. Our members have done extremely well.”

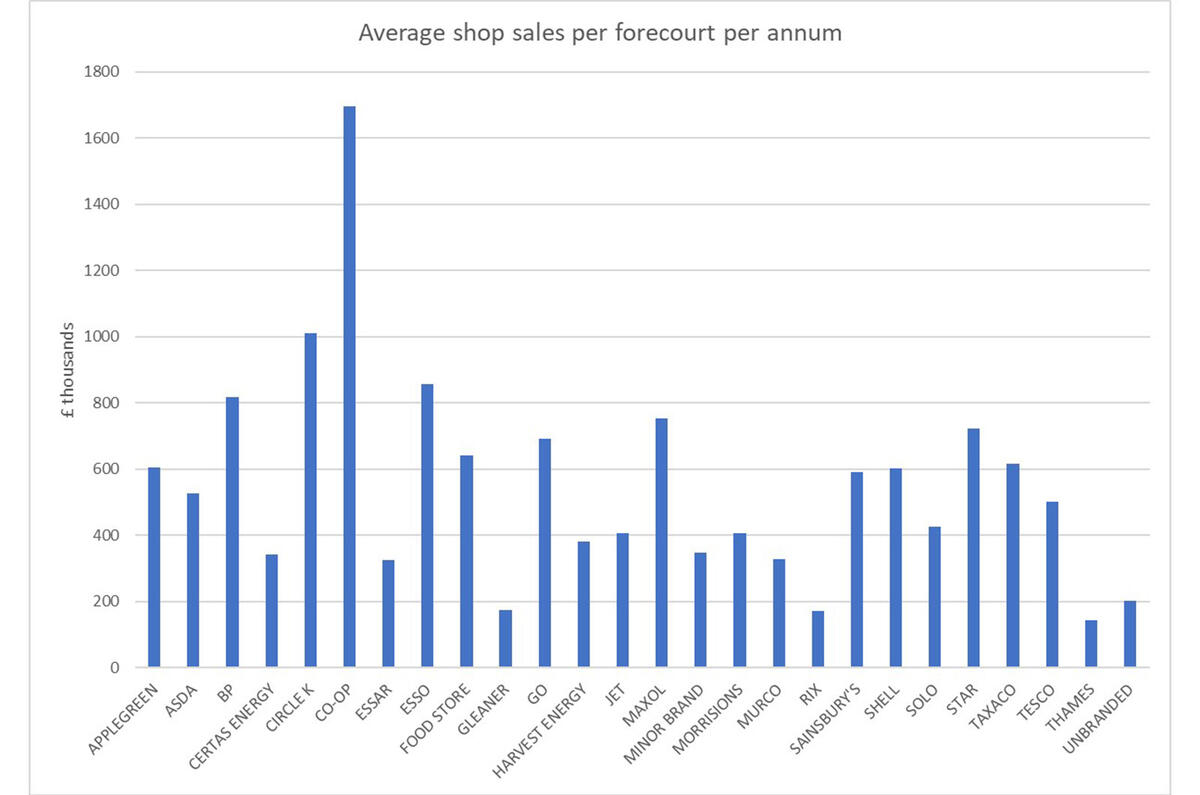

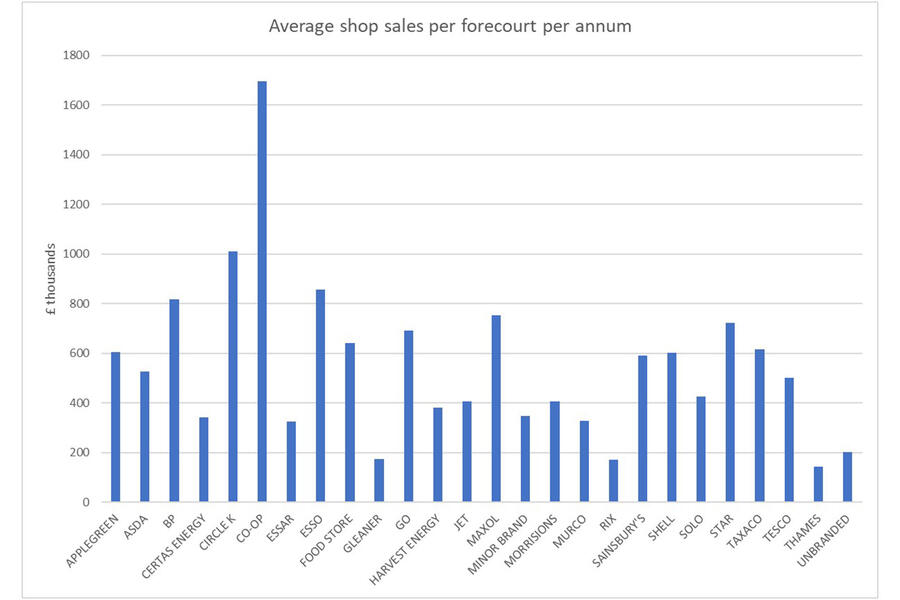

Petrol stations have been supplementing pressured fuel sales with retail arms for many years, but as a rule, those with the most developed retail offerings tend to be larger brands. Smaller, rural stations have tended to struggle to provide the same services. David Charman, owner of an award-winning rural forecourt in Parkfoot, Kent, says: “The loss of fuel sales puts an awful lot of pressure on particularly small rural forecourts. The Tesco Expresses of this world are much better set up to deal with convenience than the small rural store.”

Another major challenge faces the owners of small and rural stations: electrification. The global push towards replacing fossil fuels with electricity has caused problems with adapting this new focus to a winning business model, particularly for rural forecourts. There are issues with logistics and, relatedly, cost, not to mention technology, and Charman doesn’t gloss over these.

Join the debate

Add your comment

On the plus point they will likley have a commercial electrical supply so they will be full of the locals supercharging their EV cars. The future looks good for them for at least in the next 30 years or so.

Other rural stations have already changed, some expanded their car-repair facilities to become full mechanics/used car sales. I've seen a couple of older stations become private houses (at least one of which has kept the retro Texaco sign), whereas newer forecourt style stations tend to become hand car washes.

Maybe if they redirect the power used for the pumps into a charger, might not allow for superfast charging, but as a top-up charge?

15 years ago when I did business with petrol stations, they got the traffic in because they sold fuel and cigarettes, but they made little from them. It also typically saddled them with huge debt to the fuel companies which locked them in with a low interest loan dependant on volume sales. In a town they might make 1p or as much as 3p on £1.39 per litre. In the sticks it might be 6p or 10p on a higher pump price. It costs more to ship less fuel per site in smaller tankers to the sticks. Even then car drivers were filling up whenever they went to town rather than at the local garage.

They all made their money from food sales, and other necessities like a good corner shop used to, but with easy parking.