Grease points. Decokes. Carburettor dashpot top-ups. If you bought a new car at any point from 1928 right through to the 1970s, you would be taking on a maintenance programme to rival that of a fractious diva.

And while spending almost as many hours maintaining your motor car as you would driving it – or paying a dealer to do it – the structural core of your investment would continuously be attempting to change its state from robustly so lidsteel to crumbling flakes of rust.

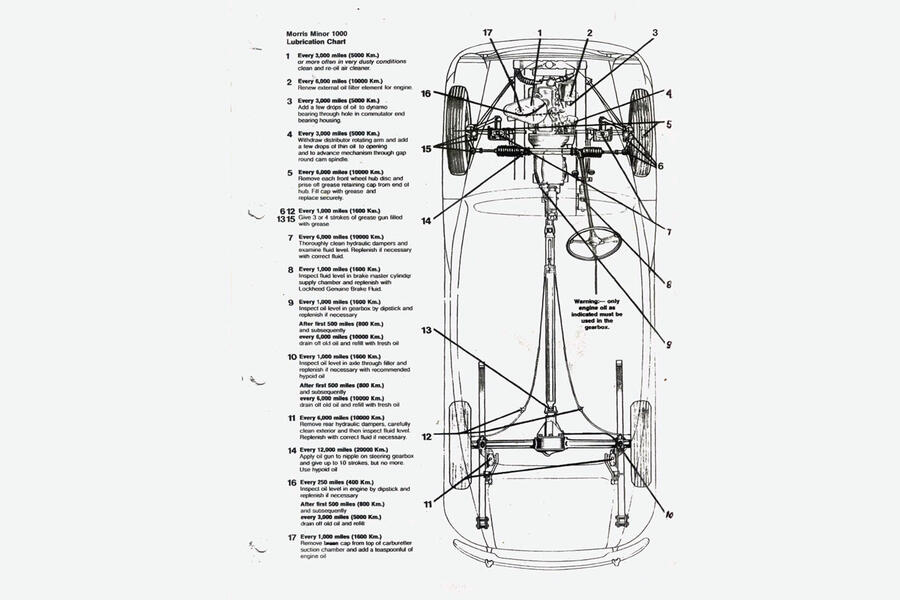

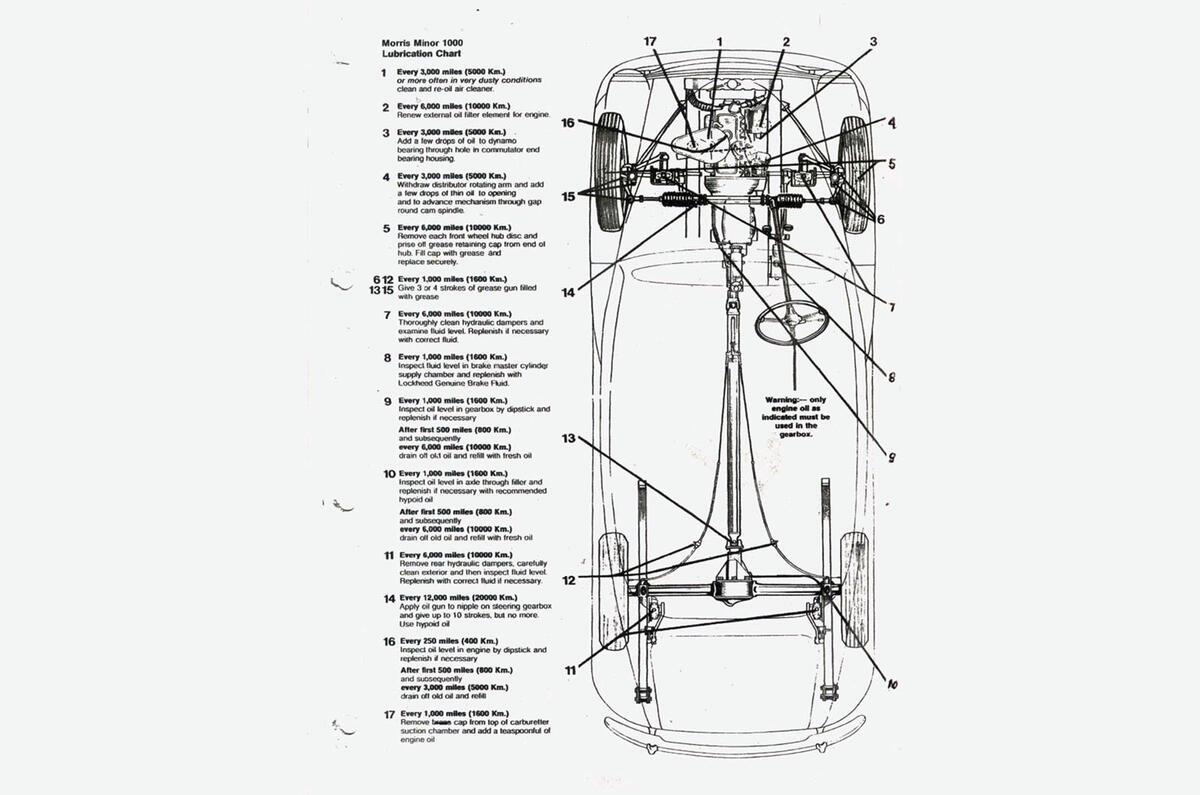

The operation manual of a Morris Minor from the early 1950s provides a clue to the scale and relentlessness of maintenance required. At 500 miles, six steering gear grease nipples required three or four strokes of a gun. At 1000 miles, the gearbox and back axle oil levels needed checking, along with the brake master cylinder, as did the SU carburettor’s dashpot. And the propeller shaft joints needed greasing.

Every 3000 miles came an engine oil change, lubrication of the distributor and dynamo, light greasing of the contact breaker’s rocker arm pivot and checking the points in the electric fuel pump. In addition to all this, there was yet more at 6000 and 12,000 miles. So the incentive for drivers to do their own maintenance was considerable. There were plenty of magazines providing advice, and car maintenance evening classes were common.

The rise of electronics, however, has closed DIY servicing off to most owners today. Now a laptop, the manufacturer’s diagnostic interrogation software and a cable into the on-board diagnostics socket are the modern way to find faults and, for the most part, fix them.

And they wouldn’t tell you how to weld in a new sill, or bodge a rusty one with newspaper and Isopon filler, as many did to deceive. Until 30 years ago, and in the case of some models more recently than that, rust would be the number one killer of cars, with decayed structural members rendering them uneconomic to repair. So as well as the mechanical maintenance, you would also need to lie on the floor, scraping and sanding sills for a repaint, or worse, paying somebody to weld new ones on.

During the 1960s and ’70s, an entire cottage industry of under-the-arches welders grew up, re-engineering the sills and rear subframe mountings of BMC Minis and 1100s and the MacPherson strut towers of Fords and Hillmans. Visit scrapyards in those days and most cars would have no more than 70,000-80,000 miles on the clock, their lives finished by crumbling bodywork and, quite likely, engines that burned oil and synchro that no longer meshed.

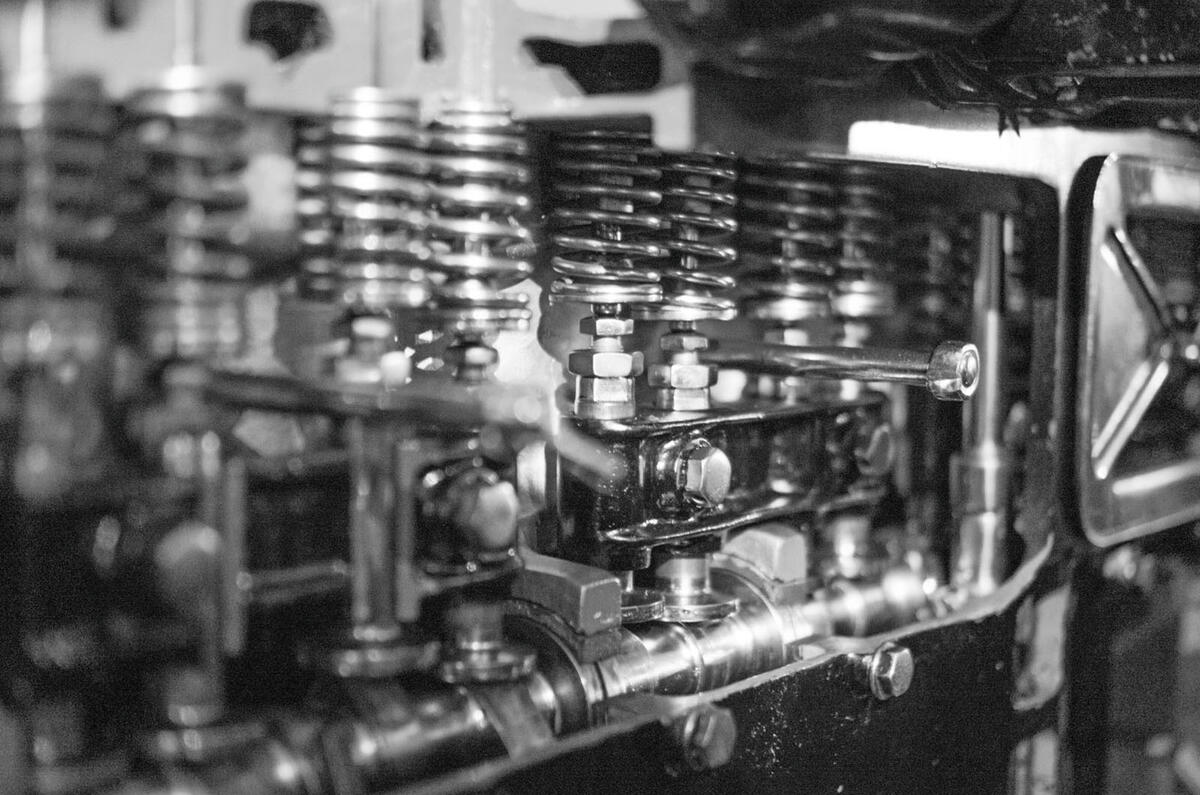

Advances in metallurgy, in high-precision machining and the greater effectiveness of oils have given engines, gearboxes, differentials and driveshafts durability that the owners of 1950s cars could barely dream of.

The same applies to bodywork. In 1928, virtually every car on British roads had a separate chassis to which bodywork made from steel, aluminium, wood and even fabric was attached. Mud, rain and road salt would attack not only the chassis but also the wood. The arrival of pressed steel monocoque bodies might have reduced the material types used, but the onset of rust in welded seams could be still more devastating. It’s only in the past 30 years that most car makers have mastered the art of corrosion- proofing bodywork.

Yet despite these pitfalls, millions of eager would-be car owners have willingly indebted themselves to get behind the wheel, the manufacturers and money-lenders dreaming up new ways to ease the financial pain (or at least to delay it) of acquiring what was usually the second-most-expensive item in one’s life after a house. The availability of credit – or buying on the never-never, or on tick, as it was once called – massively boosted new car markets, with staged payments making cars available for millions more than the few who could afford to buy outright.

Today, more than 80% of private UK buyers use a personal contract purchase (PCP), this bountiful arrangement allowing the wide-eyed shopper to acquire a more expensive machine because they only pay for part of it over the term. At the end, they either hand the car back or, more likely, take out a new PCP. Enabling punters to afford the unaffordable has been fundamental to the industry’s growth, besides allowing us to savour its fruits.

Which have at least come within closer reach since 1928, when we tested that Austin Seven England Sunshine Saloon. It cost £128 then, representing 67% of the average wage in 1934. Today, its distant descendant, a basic three-door Mini One, costs £15,905, or 58% of today’s £27,271 average salary. What comes after you leave the showroom with your new car has changed too. The rise of consumer rights, increasing mechanical reliability and the competitiveness of manufacturers have massively improved the guarantees that come with cars. During the 1970s and before, the excited acquirer would typically get no more than a six-month manufacturer’s warranty, limited to 6000 miles and with no guarantee against corrosion. The process of committing yourself has inevitably changed, too, although not as much as one might expect, with most new car sales occurring on the premises of a franchised dealer.

Buyers might carry out most of their research online, both into the car itself and finance, but they still like to see and feel the metal before signing, and to talk to a human while doing it. Some things, it seems, do not change.

Safer by design:

Besides being more durable, cars are massively safer now than they were even 40 years ago, never mind 90. Front and rear crush zones, seatbelts and grippier radial tyres were the first real life-savers, followed by projection-free dashboards, airbags, ABS, ESP and plenty more safeguarding electronics.

Some makers, notably Volvo and Mercedes-Benz, adopted safety as a selling tool, but the real impetus in recent decades has been the US crash regulations and Europe’s NCAP tests, which have improved passenger and pedestrian safety enormously. With this has come a penalty, however, in terms of vehicle weight and size, and ironically given the safety implications, reduced driver visibility.

Read more

Vintage police cars: Morris Minor

Mini Cooper S Works 210 review

New Mercedes-Benz EQC: all-electric SUV revealed

Join the debate

Add your comment

Triumph Herald ....

...I had to tie the doors together across the car from side to side with bungees to stop them flying open. If you lifted the floor mat you could see the road go by underneath. Hard braking could flip the tip up bonnet open obscuring the view. The weird rear suspension would tuck in if over enthiusistic resulting in a spin..... ah nostalgia....

Feeler gauges

A set of feeler gauges was an essential piece of equipment for running my Vauxhall Viva HB. Monthly re-setting of the contact breakers points and spark plugs was required in order to avoid the engine from pinking.

I also new the wife was the girl for me when she confirmed that she regularly removed the plugs on her Morris Marina and cleaned them in order to ensure it started.

Servicing, never been easy

"The rise of electronics, however, has closed DIY servicing off to most owners today." Just the opposite in my experience.

On some cars change the oil/filter/ cabin filter every 18,000 miles, plugs every 36,000, air filter 50,000. Everything else is just a cash cow for the Main dealers garage.

I save hundreds every year by doing the above on all 3 of my cars. Way easier than 20 years ago.