The tall ship Pelican of London looks for all the world like it has always been a graceful large sailing ship.

But you wouldn’t have thought that if you’d seen it plying the northern seas in the 1950s, when it was a French Arctic fishing trawler called the ‘le Pelican’, with no big masts, no sails and running on diesel engines alone as it fished around the Arctic’s cold unwelcoming waters.

And you’d definitely not have thought so if you’d have caught it full of smuggled vodka in 1993, when it was seized and impounded for an extended amount of time by Norwegian authorities.

Today’s Pelican is a rather more noble ship with a more noble cause than a smuggler’s vessel. A charity called Seas Your Future operates it as a sail training ship with the mission “to educate young people, through the provision of sailing or sailingrelated activities and other training”.

It’s crewed by a mix of those youngsters, plus experienced crew and science officers. Pelican takes these crews and sails mostly around Europe during the summer, with transatlantic voyages during the winter.

Within weeks or just days of departure, young people who may have never set foot on a boat before can be out of sight of land and scaling Pelican’s vast rigging to unfurl its sails.

Technically, Pelican of London is a three-masted barquentine – a three or more masted ship with a ‘square-rigged foremast’. Square-rigging means that the sails, sort of loosely square-shaped, hang down from horizontal spars, or yards.

Of Pelican’s three masts, it’s the mainmast, the big central one, that is the squarerigged one, rather than its foremast, although that doesn’t seem to matter to its type. It is a Class A tall ship, which means a ‘square-rigged vessel (and all other vessels) over 40 metres (131 feet) length overall (LOA)’.

With some fluidity, tall ships are classed and defined, perhaps counterintuitively, by their length rather than how tall they are, because that tends to come as a natural result of their length.

At 45m long, Pelican of London is one of the shorter Class A tall ships, although its highest point is still 30m above the sea. But the short of it is that there are only a few dozen of these elegant sailing ships in the world, and fewer still that operate in a sail training non-profit capacity.

As a prominent one of them, Pelican is capable of navigating any ocean in the world with a mixed crew of expert old hands and complete novices.

Very much among the novices, we joined Pelican of London for a day off the south coast of England before it departed on its winter voyage

Design and engineering

Le Pelican was built in Le Havre, France, by Chantiers et Ateliers A Normand and put to sea in 1948 as an Arctic trawler. It was “not an ice breaker, but was ice class”, explains Pelican of London’s captain, Ben Wheatley, as we sail off the south coast of Devon today.

An ice-class ship has a thicker hull than normal and more interior strengthening because it runs an increased chance of running into something solid.

After nearly 20 years of trawling as le Pelican, from 1968 it was bought, renamed Kadett and used as a coastal trading ship around Scandinavia. Its traders were not always entirely above board and in 1993 were arrested for trafficking an entire cargo of vodka from Finland.

After being impounded, Kadett became an excise sale. Former Royal Navy commander Graham Neilson bought Kadett, registered it as Pelican of London in 1995 and set about having it restored as a ‘mainmast barquentine’, a process that took 12 years.

Converting a diesel fishing trawler into a tall ship doesn’t sound to us like the most straightforward job in the world but, as Wheatley explains, Normand was a long time builder of sailing boats too and the influence of its hull design was retained in its powered ships.

In fact, the history of the Normand shipyard stretches back to 1738. It moved to Le Havre in 1816 and by the turn of the 20th century it was building everything from pilot boats and fast torpedo boats through to vast racing yachts and naval destroyers.

A century later, back in the UK, Pelican of London’s modifications included fitting “a box keel all the way underneath”, says Wheatley.

It’s hard to see or imagine the full scope of the changes, because people didn’t carry cameras around Arctic seas in the 1950s, and if you image search for ‘Kadett 1950’, you end up in rather more familiar Autocar territory.

After its conversion, Pelican has an overall length of 45m, a hull length of 34.6m, a beam (maximum width) of 7.03m and a depth (top to bottom of the hull) also of 7.03m in its middle.

Its draught – how far it stretches underwater – is 4.0m at its maximum and it has an air draught of 30m.

It has an overall (displacement of) 370 tonnes when ready for departure, with a gross registered tonnage (which reflects its closed internal volume and which is typically used for docking or transit fees) of 226 tonnes.

Pelican of London set sail for the Caribbean from Weymouth, Dorset, in September 2007 as a three-masted sailing ship for the first time, with trainees on board just like today.

Interior

You can effectively split Pelican of London’s interior, or at least its working levels (because some are outside), into three.

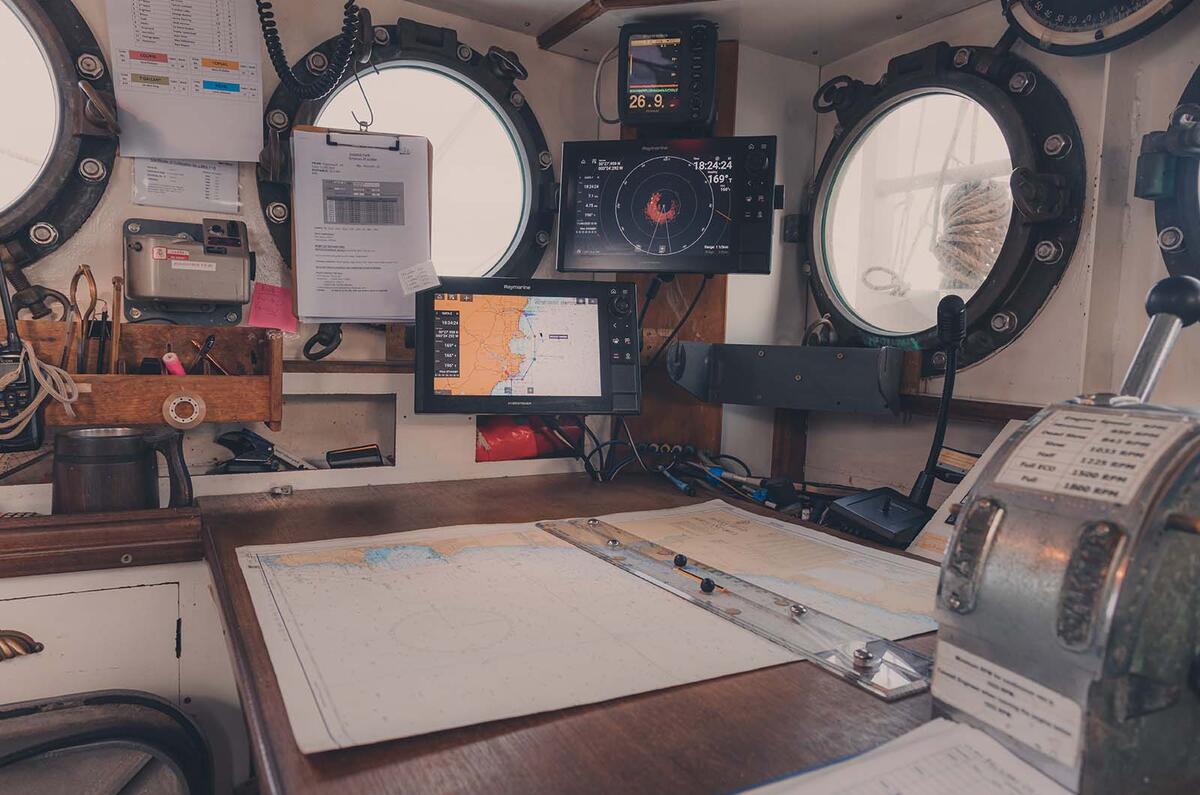

The top level is the ‘poop and fo’c’s’le’, which incorporates the upper deck at the front, the fo’c’s’le (forecastle), from where you access the frontmost mast and the anchors. Then there’s the poop deck at the rear, from which the rear mast is accessed, where the wheelhouse for piloting the ship is, plus where a rigid inflatable boat is located.

Below that is the main deck, on which sits the well deck. That’s the partly covered one front-middle. Directly behind it, underneath the poop deck, is the hub of ship activity.

The galley and mess is inside there, plus officers’ cabins, a communications room, and a saloon for the permanent crew. On this same level, at the front, is an engineer’s workshop.

From the mess and the workshop, there are stairs down to the lower deck, which is where you find most of the crew cabins, plus the provisions lockers for food, and at the very rear a gallery over the engine room, which houses generators and water makers too.

There is a lower level still, right at the bottom of the ship – the engine itself at the back, and bilge storage accessible via hatches in the floor in the lower deck – all of which have supplies crammed into them.

Not a cubic centimetre of space is wasted. Bulkheads and doors abound, with their frequency and strength a legacy of the ship’s ice classification.

Weather-tight doors have two or three locks. Watertight ones have eight. But all have heavy latches to secure them when open because all could cause your fingers a mischief. Wooden doors open onto crew cabins and are rather more civilised.

Officers have private cabins but the crew mostly sleep four berths to a cabin, each room with its own WC and shower. They’re tight on space, but given the ship is crewed in a three-watch system (three teams doing fourhour stints/watches), it’s unlikely all four cabin-mates will be kipping or washing at the same time anyway.

Performance and handling

There are two types of performance to consider with Pelican.

The less interesting one is that provided by a 9.0-litre John Deere turbo diesel engine making 325bhp, which can propel the ship at a maximum of 7.5kts and whose 15-tonne fuel tank could make it cover around 1500 nautical miles at a steady speed, which is enough to go from the UK comfortably into the Mediterranean, or about halfway across the Atlantic.

A helpful range in a fix, then, but not really the point of Pelican as a sailing vessel.

Raise or unfurl its 11 sails and all the time there’s wind its 525m2 of sail area can generate much more power than the engine, in ideal conditions taking Pelican to 10kts or more – which can make it faster than the wind that powers it in optimal conditions. A trip across the Atlantic can take “anything from 16 to 25 days”, says Wheatley.

Pelican doesn’t go searching for the worst of it but a trade breeze is ideal and there’s a reason that trade routes developed in the way they did. “Pelican will seek to follow them, so it’ll take the same routes ships have done for centuries,” he adds.

Pelican’s advantage over most of those old ships – and nearly all current tall ships – is that its square-rigged booms can be angled so far from perpendicular to the ship.

“No other tall ship can have yards as sharp,” says Wheatley, which means they can be angled to take much better advantage of what would otherwise be a suboptimal, or impossible, wind direction.

Instead of being forced to zig and zag to travel from place to place, Pelican can travel, perhaps slowly, but more directly, with a wind at anything up to 70deg across while still making acceptable forward progress.

Ideally, says Wheatley, the fastest would be “a soldier’s wind”, coming at 45deg across the back of the ship, in which more than 10kts is achievable with no drama.

Steering is a little more vague than in modern ships, using the big wheel outside behind the wheelhouse, keeping to a heading specified by the captain, and registered on readout above the wheelhouse door – although there’s also a magnetic compass, should that go down.

Steering is light, partly owing to the large-diameter wheel, which increases its leverage. But it’s slow. “Nothing happens, nothing happens, nothing happens,” says Wheatley, “then it starts to turn and won’t stop until you unwind and over-correct. It’s like an American car in a film chase.”

You don’t get what we might call steering feel back, but you can stand at the back with a cup of tea, a lookout to keep an eye on things, hum sea shanties, and have a very nice time piloting a beautifully mechanical vessel.

Wheatley says that under engine power you could pilot the ship with as few as seven people, which is useful for hopping from one place to another.

You could long-term sail with as few as 16 people aboard but you’d be working pretty hard. A typical crew is 30-40 young people learning the ropes, so to speak, and seven or eight permanent crew.

Buying and owning

An unlimited range with no fuel consumption doesn’t sound like a bad ownership proposition, does it?

But running the Seas Your Future charity with one ship costs around £3500 a day, 30% of which comes from charitable donations and the rest by fare-paying youngsters, who come aboard to find out more about their future.

It’s particularly popular with mainland European kids because they can learn English at the same time. Given the running costs, as you would expect, they like to work Pelican hard.

It runs 47-48 weeks of the year if possible because downtime is unprofitable and they don’t like doing transit journeys, like the one we joined, wherever it’s avoidable because it’s like running a car transporter with no cars on the back. You have the costs but no offsets. But there’s no problem getting the crew.

And as a result of Pelican’s popularity, Seas Your Future would like to run another ship. It has one, the Fridtjof Nansen, in dry dock under restoration at the moment, which is a big ongoing project for which it could do with some funds.

If it gets it, it could be spreading its low-carbon training of young people around the world to double the extent it is now, which is a very worthwhile thing.

Add your comment