The upcoming 2030 ban on new petrol and diesel cars will transform UK motoring on a scale never seen before. This story is part of a wider analysis of the challenges faced by consumers, government and the automotive industry, what needs to happen, and how such drastic changes can be achieved over the next decade.

Read the rest of this series here: Countdown to year zero - what needs to happen by 2030?

What's the prognosis for better batteries in the next nine years?

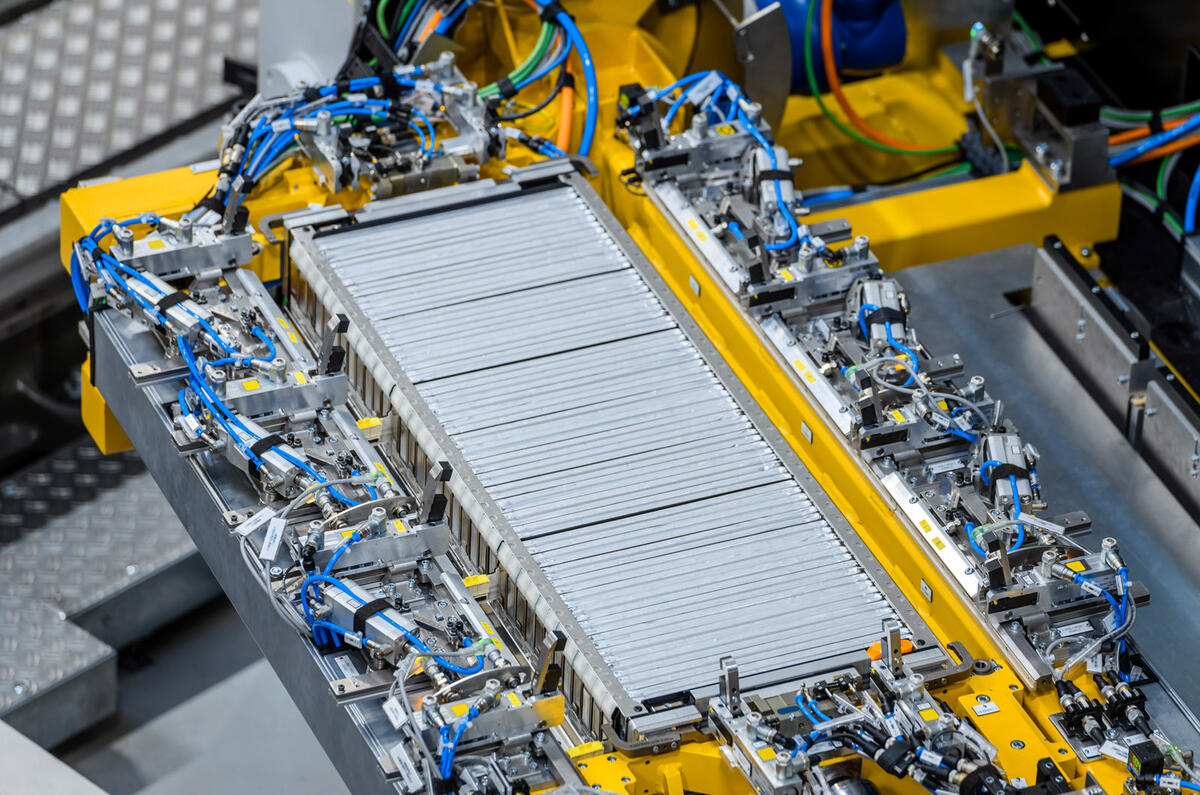

Batteries continue to get better, and although there hasn’t been a step-change yet (such as solid-state or a different type of battery chemistry altogether), improvements have come from internal packaging, software and cooling. The latest EVs with 800V ultra-rapid-charging capability are an example of that, but lithium ion batteries are still too big, heavy and costly for mass EV roll-out.

Is the vaunted solid-state battery likely to be a goer?

These are seen as the holy grail for battery-electric vehicles. The difference between a solid-state and conventional lithium ion battery is the electrolyte, which is solid rather than liquid. It’s far safer, has double the capacity and charges quickly.

Toyota is considered a leading player in the field, having been working on the technology for the best part of a decade. According to a report by Nikkei Asia, Toyota expects the battery to deliver twice the range and be able to take a full charge in 10 minutes, and the plan is to show a concept car powered by one this year. Toyota isn’t alone; all battery cell manufacturers are hard at work researching the technology. If and when it arrives, maybe in the next five years, it’s likely to be a game-changer.

Could other tech, such as ultracapacitors, emerge?

Apart from liquid fuels, batteries are by far the most successful method of storing electrical energy for cars, because they’re energy dense (high capacity). Ultracapacitors store and release electricity quickly, are power-dense and are good for boosting power, but they don’t get close to the capacity of a lithium ion battery. As of today, there’s no production-ready alternative electrical storage technology that’s even remotely close to stealing the lithium ion battery’s crown.

What other areas of tech most urgently need development?

Storing enough sustainable energy on board a car to give a decent range and allow fast replenishment (charging or refuelling) is still the main area that needs development to achieve parity with conventional cars in the convenience stakes. There’s also more scope for reducing weight and improving the overall energy efficiency of EVs, such as thermal energy management to put waste heat energy from motor, battery and inverter cooling systems to good use rather than wasting it. Every scrap of energy equates to improved sustainability and increased range.

How good are today's electric motors and power electronics?

The latest breed of AC brushless motors (electric machines) typically have a peak efficiency of around 95%. That means 95% of the electricity fed to the machine is converted into torque and only 5% disappears through heat, friction and electrical losses. The same is true of the inverters that turn DC current from the battery into AC current for the machine by electronic switching. They typically run at between 95% and 100% efficiency, but it’s getting better as manufacturers pay more attention to the finer points of electric machine and power electronics design. An example is the use of hairpin windings (tightly packed strips of copper) replacing traditional coils of wire to make easier-to-manufacture, smaller motors. Traction inverters, which control an EV motor, are under scrutiny too, and new emerging designs are smaller, lighter and more powerful.

What has Formula E taught us?

Formula E cars essentially use the same type of lithium ion battery, inverter, motor and transmission technology as any road-going EV, and every car genuinely is a rolling research tool for getting the very best out of each part of the system. In Formula E, companies developing the technology are from the mainstream and include semi-conductor companies, software developers, charging network companies (like ABB, a major series sponsor) and well-known partners such as Bosch, so the acquisition of knowledge is valuable.

Gen3 cars (2022/23 season) will be spectacularly advanced, with the rules including 600kW fast-charging during pit stops and qualifying/attack mode power of 350kW. Regenerative braking will produce 600kW split between front and rear axles.

How much performance (power and range) can be squeezed out of batteries and how to develop the software algorithms to do that, thermal management of the entire electrical system, improvements in drive motor power and efficiency and the software controlling them, plus improved inverter and semi-conductor design, including the motor control software that goes with it, are all useful for road-going EVs.

Is there a future for synthetic fuels? Some say they can be carbon-negative. Is that true?

It’s no secret that the quickest way to reduce the CO2 emissions across an entire fleet (like all the vehicles in a country or the world) is to change the fuel in existing vehicles. Combustion engine ban on new cars or not, conventional cars will be around for a long time yet, and there are 1.4 billion of them worldwide. Biofuel and synthetic fuel can both reduce CO2 but are quite different things. Ethanol (blended with petrol) is an alcohol made from the fermentation of crops, while biodiesel is made from a variety of sources including vegetable oils, used cooking oil and fats. Petrol blended with 5% ethanol (E5) and diesel with 7% biodiesel (B7) is already on sale in the UK and E10 petrol is due to be introduced this year. Sustainable biofuel reduces CO2 simply by replacing fossil fuel to reduce tailpipe emissions, but that relies on biofuel production and distribution being carbon-neutral.

Synthetic fuel is made from hydrogen and carbon combined to produce synthetic versions of petrol, diesel or natural gas. The source of carbon can be atmospheric CO2 or CO2 captured from industrial processes. Its carbon-neutrality assumes the energy used comes from sustainable sources, but it’s generally thought that the carbon footprint of synthetic fuel can be far more transparent than that of biofuels. The major downside of synthetic fuels is the high cost, so kick-starting serious production of it in a hurry would probably require legislation and subsidies.

Can hydrogen fuel cell tech be useful in nine years' time?

It’s such an elegant solution, using the world’s most abundant element (hydrogen) to generate electricity without any toxic emissions. Yet despite several decades of development, hydrogen fuel cell technology for cars is still waiting in the wings. That could be about to change, though, because energy companies throughout Europe, including National Grid, are planning Europe-wide hydrogen networks to deliver clean energy. The lack of hydrogen filling stations has been a barrier to launching fuel cell electric vehicles, but the use of hydrogen generally in energy networks might help change that. Significant numbers of FCEVs in the UK by 2030, though, is unlikely.

How are batteries recycled at the end of their life?

The bad news is that although lithium ion EV batteries are robust and can be reused in secondary applications like energy storage, the chemical and mineral materials, such as lithium, manganese, nickel and cobalt, aren’t easy or cost-effective to recycle. Current EU regulations only require 50% of a battery’s weight to be recycled, which covers the basic parts like the casing, plastics, aluminium and copper, but that will have to be addressed as battery production gets into its stride.

Is there a concern about mining and processing rare earth metals?

Yes. Think about it. Why replace an unsustainable technology (fossil fuel-based powertrains) with another unsustainable technology? There are 17 rare earth elements, and although not all are that rare, with worldwide reserves of about 120 million tonnes, their extraction involves toxic processes. Availability is questionable, too. The largest reserves and mining operations are in China, but when it stopped exports in 2010 for a time, prices rocketed. Neodymium is the key rare earth element used to make the permanent magnets in permanent magnet electric motors, the favourite choice for EVs for ease of control and high power and efficiency.

What will constitute substantial EV range? Will 'self-charging' hybrids persist?

Range anxiety is touted as being one of the biggest concerns potential buyers have over switching to an EV, but how much range is enough? EVs can already compete with conventional cars for range, but ultimately range comes down to battery cost, and today there’s still a substantial price penalty for that. A range of 250-300 miles is becoming commonplace and adequate for most drivers, but not for those doing serious motorway mileage.

However, according to Bloomberg NEF’s annual battery survey, cheaper batteries are on the way. The average EV battery cost has fallen by 89% since 2010 and by 13% to £101 per kWh since 2019. The survey also anticipates a further drop to £74 per kWh ($100 per kWh) by 2023, the magic number where EVs are expected to cost about the same as their conventional equivalent. Factor in the expected proliferation of ultra-rapid-charging stations and concerns over EV range should begin to disappear, along with any kind of hybrid.

READ MORE

Countdown to year zero: what needs to happen by 2030

Official: Government to ban new petrol and diesel car sales in 2030

Join the debate

Add your comment

A long way to go (as mentioned) and too expensive for the average person, if the 2030 deadline was meant to speed up uptake of electric cars its done the opposite for me, the idea of paying £40-50k on a similar sized, comfortable and tech laden car as my 3 year old euro 6 petrol car i paid £26k for, even with the benefits it simply doesn’t add up financially and yes i know you can buy cheaper electric cars but really I don’t want to downgrade to something worst and less practical but cost me the same especially now with the way this pandemic has changed the way office people like myself work is simply idiotic, without the commute, My petrol car isn’t damaging the environment much as I’m now only doing 10-15 miles a week not 300 miles i was doing. Don't get me wrong I would have considered a plug in hybrid as a next vehicle this year as they seem a good mix of convenience and electrification for the environment and with electric charging at my work it would have been s possibility but now I’m working from home in the knowledge I’ll never be going back to a 5 day a week I simply can’t justify £500 a months on a pcp for a new car, surely the government can meet its co2 goals by office people working from home, reducing traffic in cities anyway.

What a lot of people don't want to understand is, that development takes time, they can't have the idea and put it in cars the next week!, Toyota with there 800v charge in ten minutes sounds interesting, that really would be a no brainier if that's how EV develops.

So, summing up...There is still a long way to go before EV's are as practical, sustainable and affordable as ICE cars and fuel cells aren't even on the horizon.