Under an array of gleaming white tube lights, an endless procession of Nissan Qashqais and Leafs trundles towards the end of Trim and Chassis Line 1 at Nissan’s Sunderland plant.

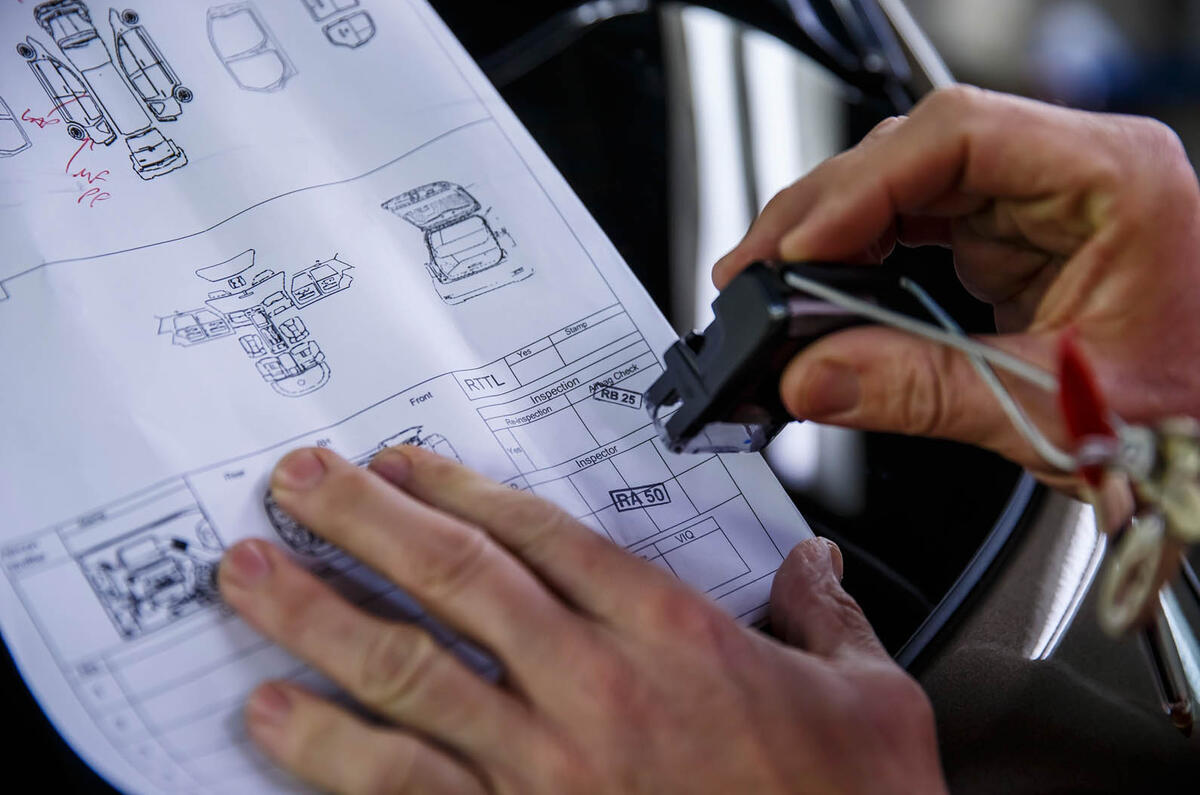

White-gloved like Tokyo taxi drivers and even more attentive, the inspectors have just under 60 seconds each to poke, ponder and fondle their allocated section of automotive anatomy before the relentless conveyor ushers the car on towards the big, wide world.

This is the UK’s most productive car plant, churning out 116 cars per hour and nearly half a million every year. One in three cars made in this country is built here by a workforce of 6700 people. Yet each of the five models the factory produces began as a designer’s scribble. For the pioneering Qashqai that kick-started the crossover revolution and the smaller Nissan Juke (which shares Sunderland’s second line with the Note and Infiniti Q30), the design element was home-grown, too, conceived and refined at Nissan’s European studio in Paddington, central London.

We’ll explore the production line later, but the main reason we’ve come to Sunderland is to uncover the design process that leads from drafting-paper doodle to production car. And to help make sense of it all, we’ve brought Autocar’s in-house car designer, Ben Summerell-Youde, who creates most of the speculative renderings you see in this magazine, artfully predicting upcoming models with considerable success.

We’re focusing on the extrovert Gripz concept, which Nissan presented at the Frankfurt motor show last September to float the idea of a Z-car crossover. As with all of Nissan’s major design projects, the brief was tendered across the company’s four design hubs: Paddington, San Diego, Beijing and the creative HQ in Atsugi, Japan. Designs are submitted anonymously – the decision makers know neither the designer nor the hub that produced each proposal – but for the Gripz, the winning exterior was penned in London and references the works 240Z that won the 1971 East African Safari Rally.

Join the debate

Add your comment

Alias 3d Modelling

The Alias modeller/sculpter skillfully makes a 3D computer surface model based on the designer's sketch, but also based on an engineering package envelope that covers all criteria.

This data is then milled 1:1 in clay.

Further refinement of the clay model may be done by hand.

Your article implies that the clay modeller starts from the designers sketch. That used to be the old process, but nowadays in order to speed up the process a 3D alias surface model is first made.

This computer model can also be renderred & assessed virtualy, before being comitted to the clay model stage.