If making cars that return solid profits wasn’t difficult enough already for many European car makers, things are about to get a lot worse.

Thanks to an unholy combination of onerous EU fuel economy legislation, new economy tests and the backlash against diesel pollution, the cost of making vehicles could be set to spike by the end of the decade.

The primary hurdle is the looming European Union fleet average CO2 legislation. Due in 2020-2021, it’s been set at just 95g/km – a 60% reduction on the 2007 baseline. The figure equates to 69mpg for a petrol car and 78mpg for a diesel.

Car makers that build bigger and heavier vehicles will still have to reduce average consumption by the same 60%, but the EU acknowledges that these mainly premium brands are starting from a higher baseline.

According to the International Council for Clean Transport, this means Mercedes-Benz will probably have to hit a fleet average target of around 101g/km of CO2 in 2021. Ford is expected to have a fleet average target of 92g/km and Renault-Nissan 93g/km, while Fiat-Chrysler is expected to have a fleet average target of just 89g/km.

Until the end of last year, most car makers expected to use a combination of diesel engines, stop/start technology and further gains in aerodynamics and weight saving in order to massage down average fuel consumption to meet these EU laws.

But the Volkswagen emissions scandal blew these assumptions wide open. Many European car makers are now questioning whether diesel engines will survive in less expensive vehicles with the likelihood that new real-world emissions tests will be both difficult and expensive to meet. It’s not too fanciful to suggest that by the end of the decade, any car with a retail price under around £23,000 (the majority of new cars sold in Europe) is unlikely to be fitted with a diesel engine.

So, with the EU CO2 targets very close (at least in terms of automotive timescales) and diesel looking set to become a more premium-priced powertrain, where does this leave the European car industry?

Not without hope, because mild hybrid technology – a less expensive form of drivetrain electrification than that seen in classic hybrids such as the Toyota Prius – is maturing just in time. And much of this technology is being pioneered by UK-based engineering consultancies.

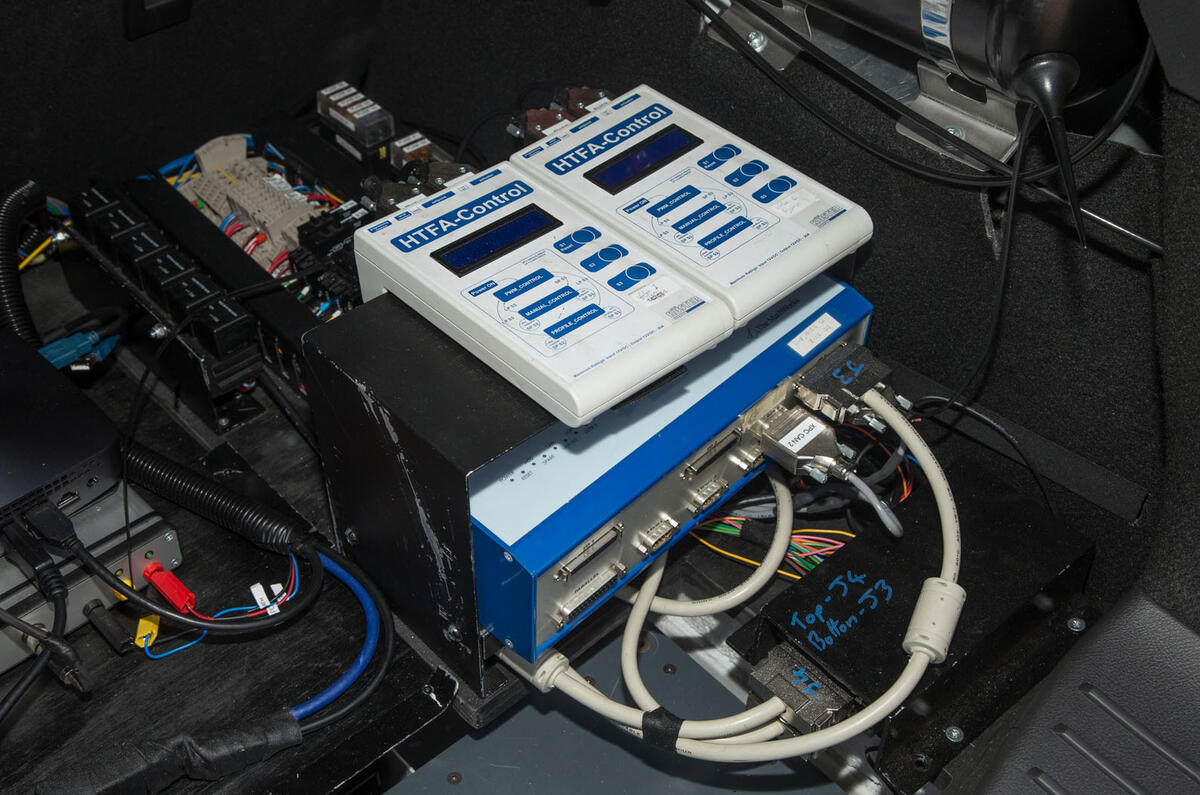

Shoreham-based Ricardo’s Advanced Diesel Electric Powertrain (ADEPT) project is just one example. It takes one of Ford’s most frugal models – the 1.5-litre diesel Ford Focus – and adds a 48V electrical system, a turbocharger, a super-fast stop-start generator and a low-cost but high-tech battery pack.

The ADEPT project is a collaboration with a host of tech companies that has been under development for three years and is being shown off at this week’s Low Carbon Vehicle event at Millbrook.

Ricardo says the production version of the 1.5 TDCi Focus is already homologated at 88g/km of CO2. While that’s below Ford’s 2021 average CO2 target across its model portfolio, it needs to be even lower in order to allow the company to sell more of its bigger and more profitable models, such as the Ford Kuga, Ford Edge and Ford S-Max. The ADEPT concept drives that 88g/km figure down to around 78g/km – but, as we’ll see, it comes at price.

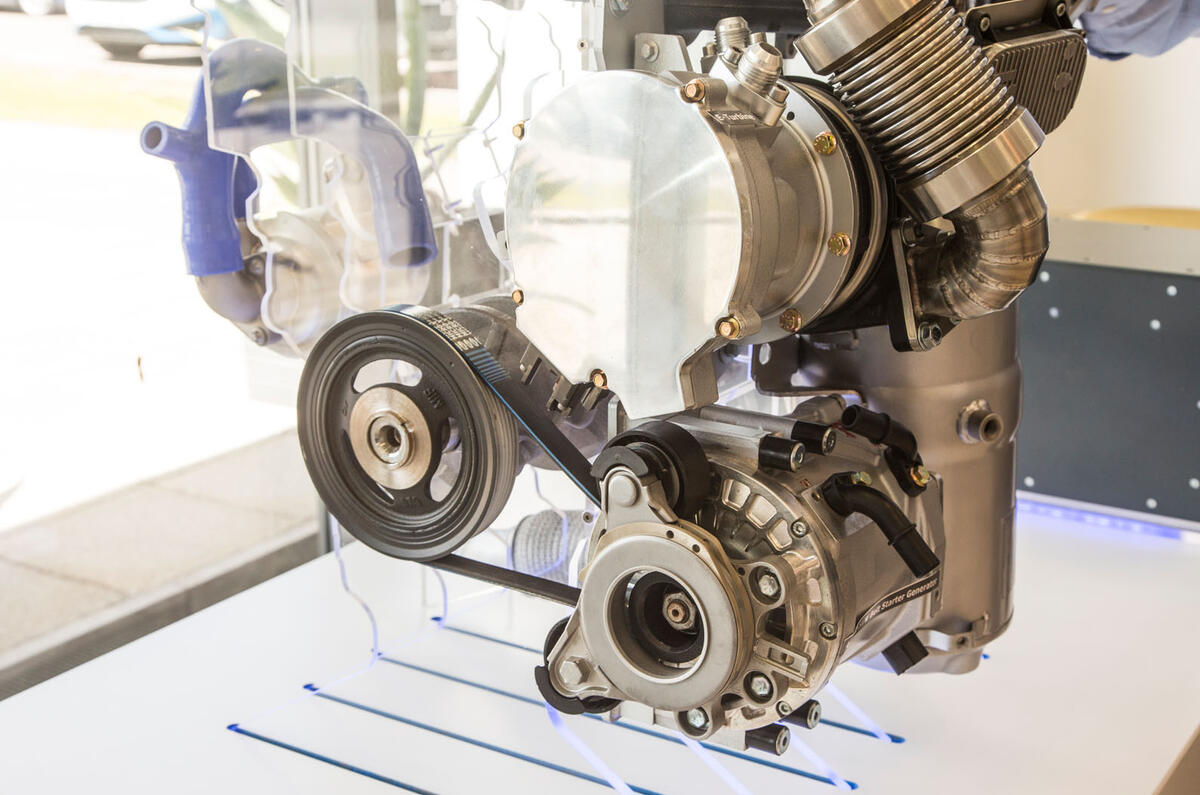

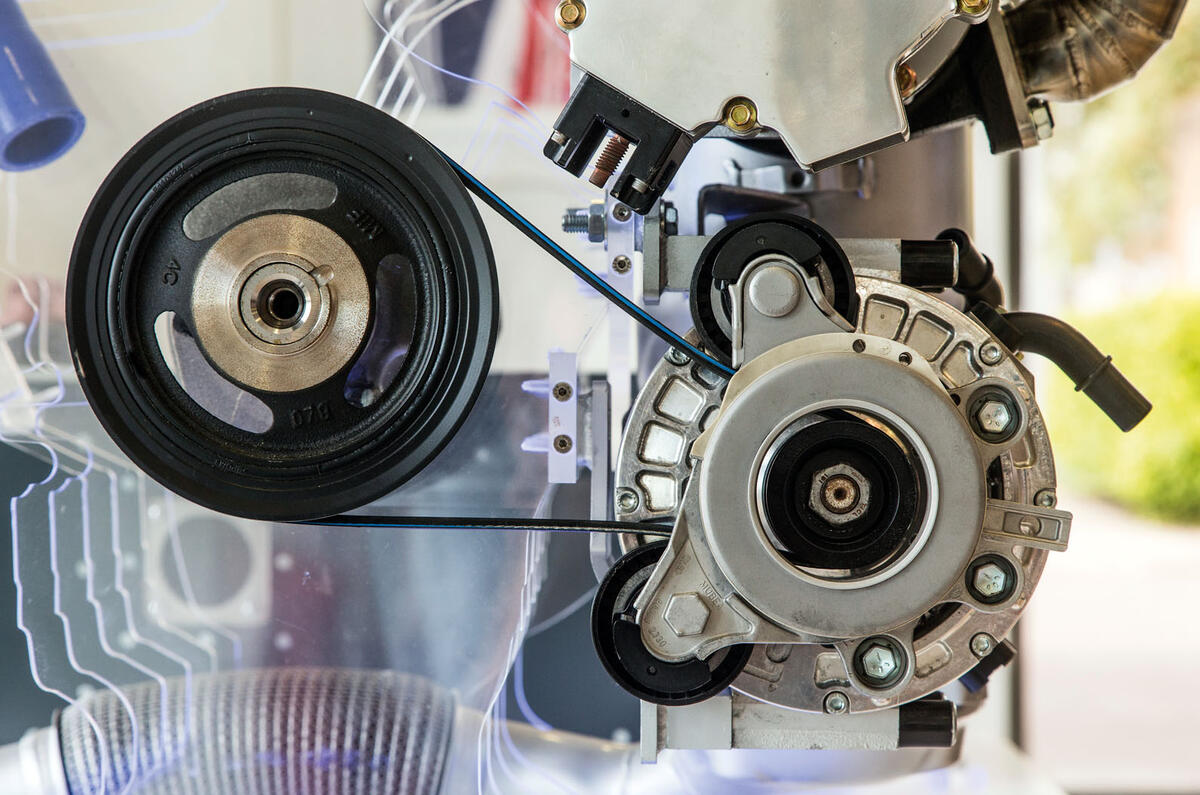

Ricardo’s mild hybrid adaptation of the Focus is extensive. Out goes the 12V alternator, the mechanical air-con compressor and mechanical water pump. In their place comes a 48V integrated starter generator (ISG), which acts as a super-fast starter motor and charger and can also assist the engine at low speeds.

ISG also provides the power for a 48V air-con compressor and a 48V water pump. A DC/DC converter is used to power the rest of the Focus’s 12V electrical systems.

The 48V battery pack is a lead-carbon unit rather than the more conventional (and expensive) lithium ion unit. This battery tech is still in development but is said to be much more tolerant of extremes of temperatures than lithium ion.

Developed by UK company CPT, the ISG is said to be up to 80% more efficient than a conventional alternator and is designed to run in two directions – one to act as a charger and one to help drive the engine. Ricardo says it can “assist the engine” by adding 7.5kW (via the drive belt to the crankshaft pulley) to the engine’s output, and when it’s being used to slow the car via the engine, it can recharge “up to 12.5We” into the 48V battery.

Ricardo’s own figures show a monumental torque curve, peaking at around 221lb ft at just 1500rpm, with 110lb ft already on tap at just 750rpm. The standard 1.5 TDCi engine produces 199lb ft at 1750rpm.

The electric water pump is also an important link in the engineering chain. When cold, an engine’s fuel consumption is much higher, because cold oil means high levels of friction. A switchable electric pump – rather than a continuously driven mechanical pump – means coolant isn’t pumped around until the engine has reached operating temperature.

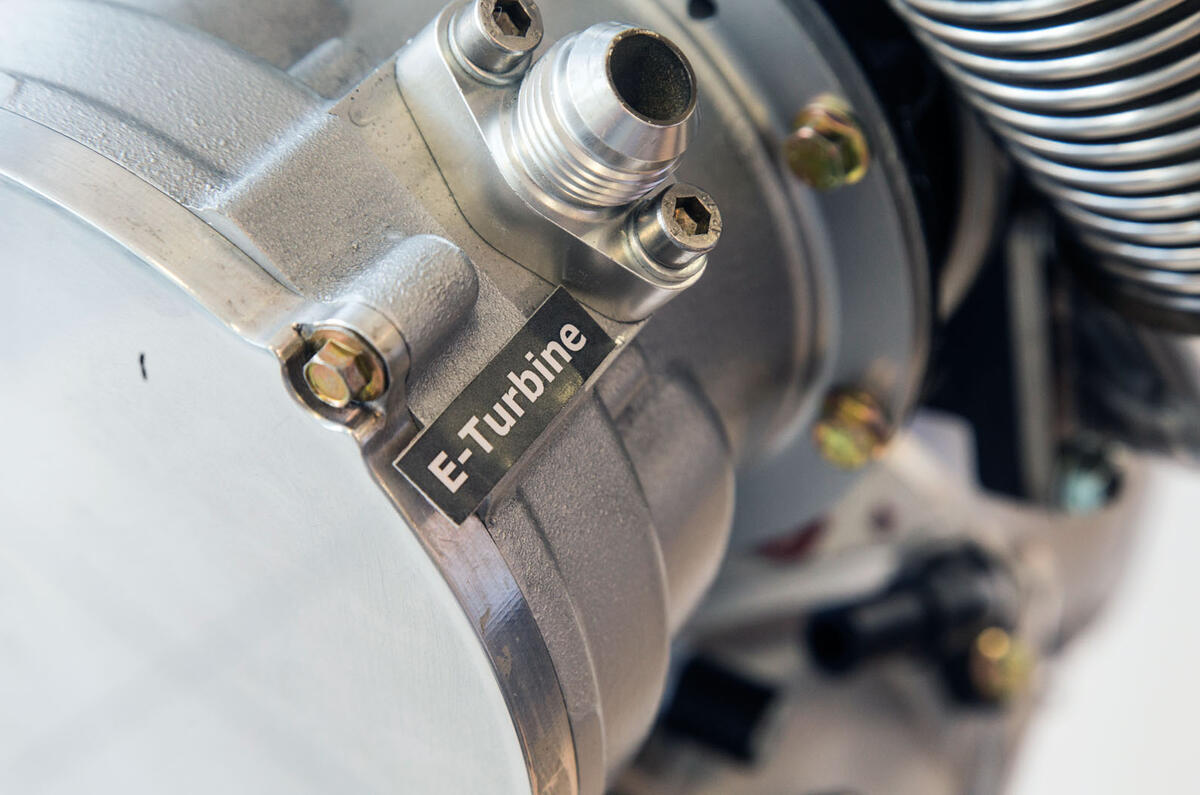

The most remarkable idea on Ricardo’s prototype is probably the Turbogenerator Integrated Gas Energy Recovery System (TIGERS) ‘e-turbine’, which sits in the exhaust stream and uses exhaust gas to drive a generator. Ricardo calculates that at motorway speeds, Tigers could recover around 1.4kW of energy to the battery.

So what’s it like on the road? Unusual, to say the least. One of the main philosophies behind the ADEPT Focus is ‘down-speeding’. Ricardo says running the engine at a lower speed – through longer gearing – reduces fuel consumption. Normally that would mean reduced acceleration, but ADEPT uses harvested waste energy to drive the electrically powered turbocharger, which then boosts performance.

On the roads around Shoreham, the ADEPT Focus felt somewhat slow and unresponsive, although much of that sensation was almost certainly due to the fact that the car was demanding I upshifted at lower engine speeds than seemed natural. After a while I became convinced that some form of automatic transmission would have been better suited to this drivetrain, because it would surely shift more quickly and at the optimum time.

Even so, in town driving it was fine, having enough low-speed acceleration to find gaps. It was on the wide open roads and long uphill drags that the ADEPT concept seemed to lack the traditional driveability drivers take for granted. Of course, the whole point of the concept is to reduce fuel use, so we can’t expect this car of the near future to offer breezy performance.

But that is the essence of ADEPT. It trades that breeziness of progress for something more regulated and controlled. In its current form, I don’t think many drivers – even those with no interest in motoring – will like it much, but how else is the car industry going to get the average Focus-class car to return 78g/km of CO2?

Then there’s the cost of the technology. Ricardo’s calculations suggest it will probably cost €80 (roughly £67) in engineering content for each 1g/km reduction of CO2. That it could add at least €800 (£674) to the factory cost of a future Focus-sized car is sobering – and not just for hard-pressed car makers.

And while you’re chewing this prospect over, the European Union is currently ‘consulting’ on what the fleet average CO2 levels should be for 2025. One thing is for certain: they’ll be even lower.

Join the debate

Add your comment

And one more thing....

Maintaining the alternative

The internal combustion engine remains the best method for powering cars, and will do so for quite some time to come, however there has to be an environmental consideration to be made and the most effective is the most overlooked. Keep cars on the road for longer.

It is far more environmentally friendly to keep old cars going than to make new ones, and a restriction should be introduced that nobody can buy more than one brand new car in any ten year period. People would choose cars for longevity and would look after their cars more carefully if they were encouraged to keep them for longer.

The EU