The modern motoring era isn’t full of technological trends of which keen drivers can unreservedly approve.

Given the chance, I suspect that most of us would take the start-stop starter-generators and electric power steering out of our new cars in a heartbeat. But the meteoric rise of the downsized, turbocharged three-cylinder petrol engine deserves an unqualified round of applause. This is efficiency innovation that we can all get behind.

Over the past three years, these engines have spread across European model ranges faster than any type of powertrain that I can remember. And standing in a car park near Brentwood in Essex in the early morning light, Andrew Fraser is explaining why.

Fraser is powertrain development manager at Ford’s Dunton Technical Centre and one of the key men behind the motor that started all this in 2012: the 1.0-litre EcoBoost. “It’s not just about weight or cubic capacity,” he says. “It’s got more to do with a combination of rotational balance, thermal efficiency, space efficiency and suitability for turbocharging.” Pay attention at the back: engineer talking.

“Three-pots have much less second-order vibration than four-cylinders,” he explains, “so they can sometimes do without balancer shafts entirely and can manage with shorter conrods than four-cylinder units, so they fit into a smaller space.

Having fewer cylinders for the same swept volume means you lose less energy as heat, and because you’ve got fewer exhaust pulses per crankshaft revolution, both turbocharging and cooling are also easier. So the efficiency gains can be made on several fronts. I’m not at all surprised that it wasn’t just us that realised it.”

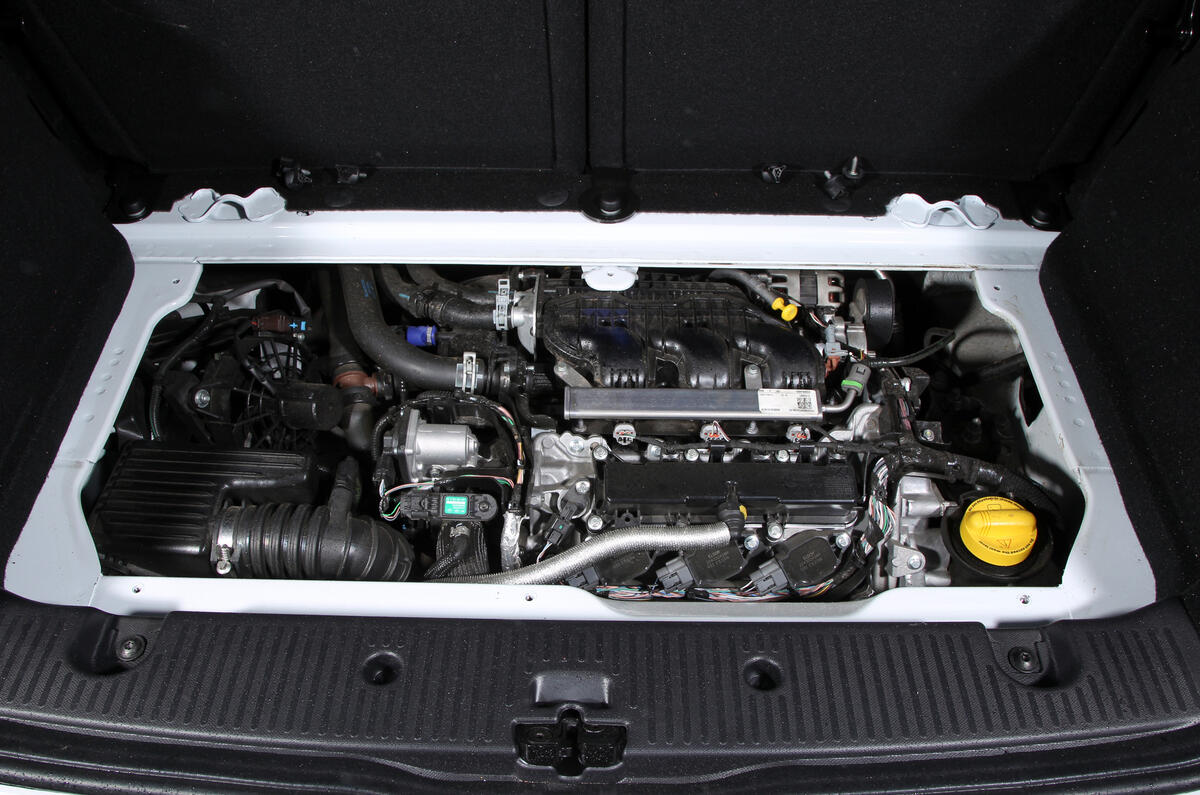

Fraser and I are looking at the evidence of that realisation: five new cars from five different manufacturers, and as many different sub-sections of the market, all of which are powered by new-generation turbo triples launched over the past three years. At the extra-small end of the spectrum is Renault’s 898cc three-cylinder turbo, nestling neatly in the hindquarters of the new Twingo city car. At the larger end is BMW’s 1499cc unit, which powers the biggest and heaviest of our group: the BMW 218i Active Tourer MPV.

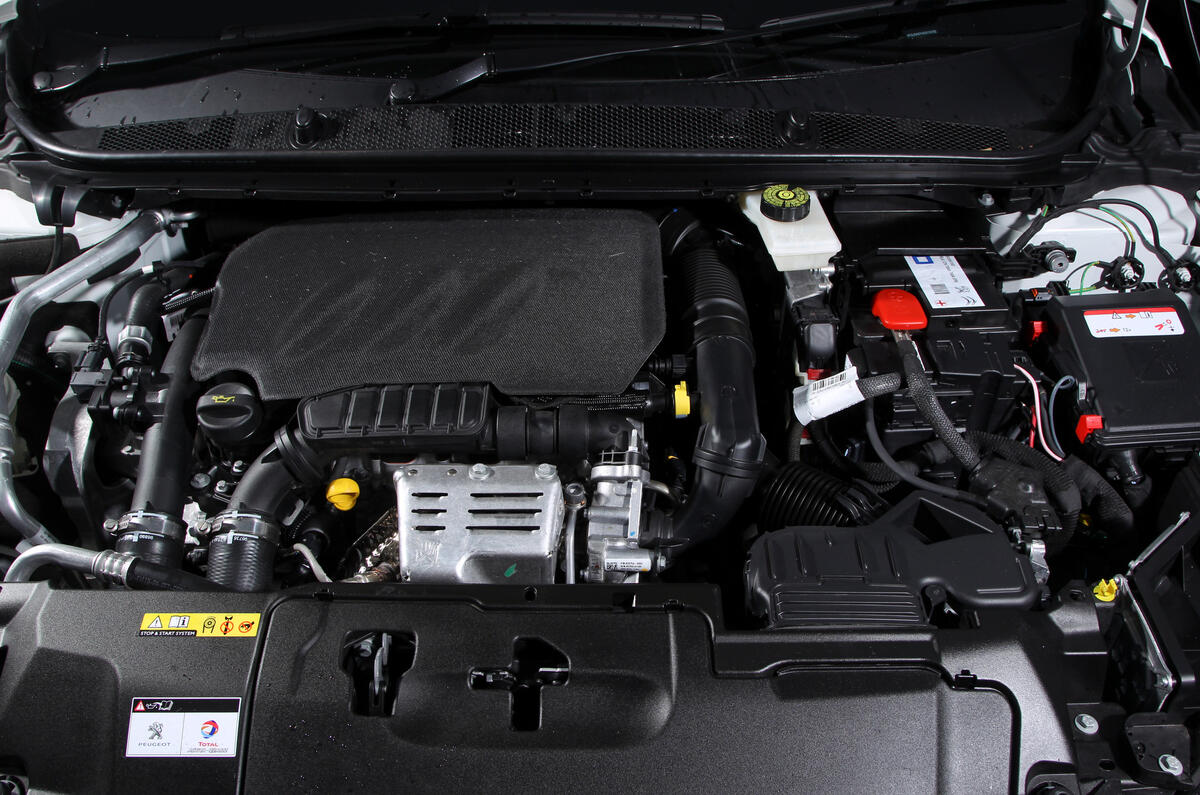

The youngest engine of the lot is in the new Vauxhall Corsa – General Motors’ SGE 999cc three-pot. Elsewhere, Peugeot-Citroën’s 1199cc Puretech three-pot lines up in the nose of the Peugeot 308 SW.

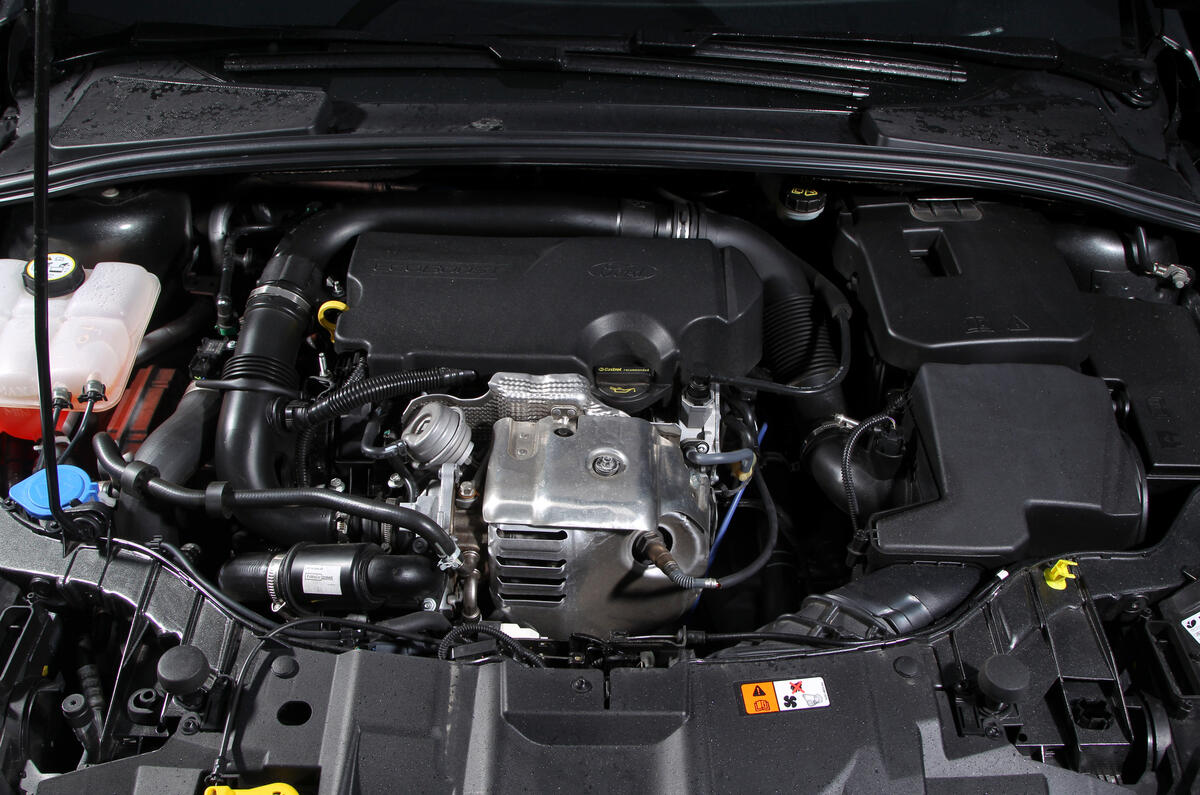

Finally, there’s the one that started it all. Having just received its third consecutive International Engine of the Year Award, the Ford 1.0-litre EcoBoost fronts up to defend its territory from within the recently facelifted Focus – a car itself so new that it’s with us in left-hand-drive form.

We’d have preferred a 1.0-litre Mondeo, just for the added diversity, but it isn’t available yet. But as Fraser gently reminds us, 20 years ago, when the original Mondeo was launched, an engineer would have been declared insane if he’d suggested that a 1.0-litre engine should power a 1.5-tonne car.

So it’s strictly engines under the microscope here – for a change. Power outputs range from 89bhp to 134bhp, torque from 100lb ft to 170lb ft, and CO2 from 99g/km to 115g/km – but that’s just on paper.

We’ve got the best part of 500 miles and two days of real-world testing ahead, starting here at Ford’s Dunton Technical Centre (where the EcoBoost engine was designed), finishing at BMW’s Hams Hall factory near Birmingham (where the BMW engine is built), and taking in a lengthy workout around our favourite roads in north Wales.

At the end of all that, we simply want to know who makes the best new-age three-pot on the block. Who’s setting the mechanical standard, which petrol triple makes the most convincing case for itself – and how convincing is that, exactly?

Performance

Assessing this particular quality seems the obvious place to begin our exercise – the northbound M1 lending its several unusually quiet lanes to explore not just outright pace but also the response and operational range of these motors.

That task isn’t made entirely straightforward when the cars they’re bolted into don’t have rev counters.

In the Twingo, you don’t get one. I like a rev counter. If you’re the kind of driver who bothers to find out exactly where his new car develops maximum power, how fat the torque curve is and where he ought to be changing gear, you probably do, too.

Furthermore, I reckon there’s a decent chance that you’d be attracted to a turbo three-pot precisely because you like your engines and generally care what they’re giving you at any single moment. Not rocket science, is it? Give us a tacho please, Renault. Ideally a nice, clear, conventional one. Not one that reads backwards and is sited on the wrong side of the instrument cluster – the kind you’ll find in the 308.

With a turbo three-pot, you have particular need of a rev counter because even with turbos, these engines feel made to rev. There isn’t a single one here that doesn’t feel elastic and relatively effortless right up to the red line, compared with an equivalent four-pot.

A short, stiff, balanced crankshaft is what delivers that remarkable quality. Where four-cylinder units produce measurable second-order vibration at 2500rpm and 4000rpm, a three-pot can better disguise the inherent refinement issues caused by tilting conrods and fluctuating piston speeds. And so the faster it spins, the better a three-pot feels.

But some feel better than others. It’s immediately obvious, for example, that the Twingo’s engine is the least potent and energetic of our group. Although the engine revs freely enough, the sudden swell of torque delivered as you come on to the Renault’s accelerator at about 2500rpm is the engine’s best trick.

It doesn’t rev through the higher reaches as sweetly as the best motors here and, dropping away from peak power at 5500rpm, it doesn’t reward you for keeping your foot in quite as convincingly.

The Corsa’s 1.0-litre three-pot shares the Renault’s bias for instant low and mid-range torque over an extended breadth of range – and that’s a bit of a disappointment for the likes of us. It was predictable. Vauxhall’s new philosophy on driveability is that torque is king. Real drivers don’t want to wait until 5000rpm for their car to hit its stride, Vauxhall says. They want performance right under the pedal.

We agree – in part. But we want high-range flexibility as well. We want truly balanced power delivery – and in rival engines, we can have it. The Corsa’s ‘Small Gasoline Engine’ 1.0-litre is certainly refined, and it’s zesty and potent enough at high revs when driven in isolation. But you can tell that the motor is past its best once 5000rpm has come and gone.

The Corsa’s wodge of mid-range torque certainly feels hefty and is available below 2000rpm, and that probably meets its maker’s engineering aims. The car climbs gradients with real authority – as well as anything else here – and accelerates from low revs likewise. But the power delivery can be a bit abrupt as it rushes in slightly behind the position of your right foot.

While we’re on the subject of response, we come to Peugeot’s 1.2 e-THP Puretech. It’s an engine that we’ve liked and rated in almost every application we’ve encountered and we like it even in this company. It revs to only 6200rpm but does so keenly, with a real turn of pace and with character and bared teeth right up to that point.

But compared with the best of the breed, it has a slightly soft pedal. We’ve chosen manual gearboxes here in order to be able to assess throttle response as clearly as possible, and the Peugeot’s is that little bit out of step with the general standard. The problem is more serious at low revs than high and can be mitigated with Peugeot’s Sport mode ECU settings. But it’s there all right. The split-second delay between pedal position and engine response is unmissable.

No such criticism can be levelled at Ford’s 1.0-litre EcoBoost or BMW’s 1.5-litre unit. On quality of performance, these two are a class apart from the rest. The Ford’s unburstable energy and flexibility are marvels and examples to all. The BMW, meanwhile, mixes most of the Ford’s zeal with remarkable mechanical refinement and polish.

For now, with the motorway behind us and the first leg of our journey done, suffice to say that the Ford’s engine puts the biggest smile on your face, followed closely by the BMW’s and the Peugeot’s.

Economy

Real-world fuel consumption next. This has been an area of criticism not just for Ford’s EcoBoost engine but also for all downsized petrol motors launched during the past five years or so. Diesels seem to easily better 50mpg in small and medium-sized cars, but small petrols require more restraint to get there.

That’s the conventional wisdom. The truth is that if you go touring in any of these cars, driving with good conservation of momentum and good observation – and not driving slowly, but committing only to putting on speed you’ve a need for – you’ll get 50mpg out of them. Any of them. Our testing had to be more varied, then, to reflect that kind of driving style. For practical reasons, our results were also recorded by trip computer, which tend to be only 95 per cent accurate.

It’s also the case that fuel economy is defined to a large degree by vehicle weight and aerodynamic efficiency, so we have neither an entirely scientific test of pure engine potential here nor a wholly fair one.

And yet four engines covered the same 450 miles, in the same conditions and at broadly the same speeds. The little cars were the most frugal, proving the point about vehicle weight. The Twingo narrowly topped the order, recording 42.9mpg, followed by the Corsa with 42.5mpg. Then came the Ford (36.7mpg), the BMW (36.4mpg) and, finally, the Peugeot (35.9mpg).

In an everyday, everyman commuter pattern of use, both the Twingo and the Corsa would easily top 50mpg and the other three would all better 45mpg.

Apply a bit of handicapping to those numbers to account for weight and aerodynamics and two engines emerge with particular credit. BMW has, of late, maintained that 500cc is the optimum volume for a cylinder. It’s evidently on to something. For a high-rise, 1400kg car such as the 218i to match a lighter, lower, smaller-capacity Ford on economy is very impressive indeed.

Vauxhall also deserves recognition for creating an evidently economical engine in the 1.0 SGE. It doesn’t offer such wonderful high-rev fireworks, but those fireworks require generous fuelling where they are on offer, which explains why you won’t see such great economy from either the Ford or the Peugeot if you go chasing the red line.

Refinement

Mechanical convention encourages us to assume that three cylinders should be more refined than four, but reality isn’t so straightforward. Fraser was right to point out that second-order vibrations tend to be less noticeable in three-pots. But he also pointed out that a refined engine needs a stronger all-round hand than that to run quiet and smooth.

Refinement at idle, for example, is an insoluble problem for engineers working on three-cylinder engines. The ‘1-3-2’ firing order that they inevitably use sets up a transverse rocking motion of the engine on its mounts which, unchecked, can make a car bounce vertically on its front suspension springs.

In modern engines fitted with stop-start systems, a rough idle may be adjudged a less important problem, but the same rotational excitement that causes the bounce can also cause the engine to shake the body torsionally as it starts and stops.

Ford’s solution is to fit a counterbalanced flywheel and pulley drive wheel on either side of the engine, to cancel out the twisting. Vauxhall’s solution, like others, is to fit a balancer shaft. Both solutions work well. There isn’t an unrefined engine here by general standards. But BMW’s is by some margin the quietest and smoothest of the bunch.

Having picked off an overtake or slowed for a corner, you can cruise for mile after mile in the Active Tourer without realising that you’ve been pulling 5000rpm and you’re still in third gear. That’s how smooth, hushed and well mannered BMW’s 1.5-litre triple is. Having the most swept volume and needing less boost pressure to make its power and torque, the engine is at an inherent advantage on refinement – and can you tell.

The manual gearbox also has synchro rev match to make downshifts oh so easy and generally forms part of the most well mannered and obliging package.

The Ford EcoBoost isn’t such a quiet operator, but you sense that it isn’t meant to be. Its high-rev silkiness earns it the nod here over the Corsa’s 1.0, which is quiet and pleasant at idle and at low revs but less soft-edged as you extend it.

The also-rans on good manners are the Twingo, which is a bit rough and crotchety at low speeds and resonant as it picks up pace, and the Peugeot. The 308 is the only car here to suffer the aforementioned rocking problem as its engine auto start-stops.

It’s more gravelly and coarse than the rest of the bunch below 2500rpm, and although it gets smoother as it revs, it obviously doesn’t get quieter. Like the Ford, it has sporting character on its side, but it’s probably the only three-pot here that could disappoint you if refinement was a high priority.

The verdict

Mid-afternoon on the second day of our road trip. The wet, steep Welsh mountains are long lost in the rear-view mirror and we pitch up at Hams Hall. End of the line.

It has become apparent that there are two excellent engines here, two good ones and one that’s just a bit ordinary. Renault’s 898cc TCE entered this test looking exposed on power and torque, and in an application like the Twingo it was never likely to claw back the deficit on its finer qualities.

It’s gently torquey, frugal and, by a country mile, the best engine on offer in this particular car. Still a good advert for the three-pot breed, too. But it’s outclassed as well as outgunned.

Vauxhall’s 1.0 SGE and Peugeot’s 1.2 e-THP Puretech show how differently these engines can be configured and tuned, and both impress in their own way.

Big on accessible thrust and economy, the Corsa’s engine is tailor-made for the disinterested driver. If you never extend it beyond 4000rpm, you won’t have missed much – and that seems to us to leave too much of the potential for the driver entertainment that is bound up in the three-cylinder concept untapped.

Peugeot’s alternative loves to rev, rewards you when you go looking for fun and is generally more our cup of tea. It makes the podium – despite being unexceptional on economy, response and refinement.

Which leaves just two: the greatest engine here and the best. BMW makes the latter. There is simply no denying that claim of something so broadly excellent: cleanly obedient, tractable, free-spinning, pacey, frugal and so singularly quiet and smooth. The BMW deserves first place.

But it doesn’t get it. Where forced induction is in the mix, we shouldn’t be concerned with cubic capacity – but you can’t help being more impressed by Ford’s achievement at producing such strength, spirit, elasticity and engagement from 999cc than by what BMW has conjured from 50 per cent more.

The EcoBoost triple may not have a hand quite as complete as its German rival’s. If you could drive otherwise identical cars powered by either engine, the BMW might impress you more with its balance of efficiency and good manners combined with plenty of sporting zeal.

But somehow, the Ford’s greater stature combines with its operating brilliance and overhauls this contest. Even after three years on sale, that first, unburstable turbo triple petrol remains the definitive one – by about the width of its cambelt.

And as a keen driver, in anything other than a 15,000-mile-a-year motorway cruiser, I think that I’d choose one over just about any four-cylinder engine on the low side of 200bhp – petrol, diesel or hybrid.

Read Autocar's previous comparison - the best depreciation-busting cars

Ford 1.0T Ecoboost

Power 123bhp at 6000rpm; Torque 148lb ft at 1400-4500rpm; CO2 108g/km; Claimed economy 58.9mpg; Capacity 999cc; Bore/stroke 71.9mm/82.0mm; Specific output 123bhp per litre; Compression ratio 10:1; Made of Cast iron block, aluminium head; Weight 97kg; Valve gear 4 per cylinder, twin cam, variable camshaft timing; Turbo Continental; Boost pressure na; Counterbalance measures Counterweighted flywheel and drivewheel; Other highlights Offset crankshaft, 'oily' lubricated cambelt

BMW 1.5 (B38 18i)

Power 134bhp at 4500-6000rpm; Torque 162lb ft at 1400-4700rpm; CO2 115g/km; Claimed economy 57.6mpg; Capacity 1499cc; Bore/stroke 82.0mm/94.6mm; Specific output 89bhp per litre; Compression ratio 11:1; Made of Aluminium block and head; Weight 108kg; Valve gear 4 per cylinder, twin cam, variable camshaft timing; Turbo na; Boost pressure na; Counterbalance measures Sump-mounted balancer shaft; Other highlights 'Volumetrically perfect' 500cc cylinders

Peugeot-Citroën 1.2 e-THP Puretech

Power 128bhp at 5500rpm; Torque 170lb ft at 1750-3000rpm; CO2 115g/km; Claimed economy 60.1mpg; Capacity 1199cc; Bore/stroke 75.0mm/90.5mm; Specific output 107bhp per litre; Compression ratio 10:5:1; Made of Cast iron block, aluminium head; Weight 80.5kg; Valve gear 4 per cylinder, twin cam, variable camshaft timing; Turbo HTT; Boost pressure 1.4bar; Counterbalance measures Counterbalanced flywheel; Other highlights Offset crankshaft, lubricated timing belt

Vauxhall 1.0 SGE

Power 113bhp at 5000rpm; Torque 122lb ft at 1800-4700rpm; CO2 114g/km; Claimed economy 57.6mpg; Capacity 999cc; Bore/stroke 74.0mm/77.4mm; Specific output 113bhp per litre; Compression ratio 10:1; Made of Aluminium block and head; Weight na; Valve gear 4 per cylinder, twin cam, variable camshaft timing; Turbo MHI, single-scroll; Boost pressure 1.5bar; Counterbalance measures Sump-mounted balancer shaft; Other highlights Variable-length intake manifold

Renault 0.9 TCe

Power 89bhp at 5500rpm; Torque 100lb ft at 2500-3000rpm; CO2 99g/km; Claimed economy 65.7mpg; Capacity 898cc; Bore/stroke 72.2mm/73.1mm; Specific output 99bhp per litre; Compression ratio 9:5:1; Made of Aluminium block and head; Weight na; Valve gear 4 per cylinder, twin cam, variable camshaft timing; Turbo HTT, fixed geometry; Boost pressure 2.05bar; Counterbalance measures Counterbalanced flywheel and drivewheel; Other highlights Graphite-coated piston skirts, chain cam drive

Get the latest car news, reviews and galleries from Autocar direct to your inbox every week. Enter your email address below:

Join the debate

Add your comment

Too bad there aren't any data...

Older 3 pot

Mileage +72,000 miles, [my miles +58k].

Mpg, summer - mid 50's, distance trips closer to 60, winter +/- 47, oveerall +/-50 .. tankful measurement.

Road Fund £130.

Driving style - spirited.

Can only see first page of comments!