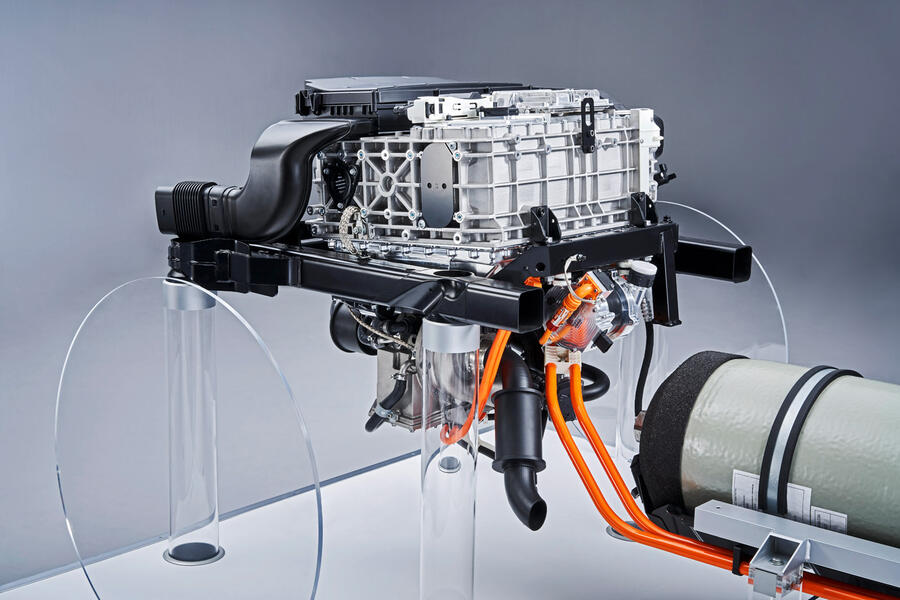

Jaguar Land Rover (JLR) has confirmed that fuel cell powertrain development forms a core part of its bold new 'Reimagine' transformation strategy, and will begin road testing prototypes within the next 12 months.

Last year, the company detailed its Project Zeus initiative: a serious hydrogen power research project with the aim of developing fuel cell-powered versions of its larger vehicles. It has now reinforced that ambition to prepare itself for "the expected adoption of clean fuel-cell power in line with a maturing of the hydrogen economy".

Should the research effort – which is known as Project Zeus – prove successful, the fuel cell technology would most likely be ready for production use around the time of the next-generation Range Rover Evoque’s arrival in the middle of the 2020s and then be used for zero-emissions versions of larger models in the future.

The Reimagine plan, detailed today, will see Jaguar and Land Rover use separate, bespoke EV architectures for their upcoming models, with Jaguar set to go EV-only from 2025. However, the hydrogen project could give it another powertrain option as the British government’s plan to ban the sale of internal combustion-engined vehicles by 2030 approaches.

Project Zeus was described by JLR product engineering chief Nick Rogers as “really, really important”. He added that the company will soon reveal a driveable hydrogen fuel cell concept car.

“We’re looking for the right propulsion systems – ones that see minimum interference to the environment,” said Rogers.

“With hydrogen, we believe there’s a key place [for it in our line-up]. We’re developing and investing in that, and we’re getting great support to do that.”

While it’s still early days and the focus is on developing the hydrogen powertrain technology, the first concept developed as a result of Project Zeus is likely to be an Evoque-sized SUV.

Join the debate

Add your comment

Autocar render in the first pic? What's happened to the roof? Can it only by driven by people of "restricted height"?

Some interesting comments, although to be honest I'm still not convinced that BEVs are better than hydrogen fuel cells.

For a start, it is known that the manufacture of BEVs is very polluting, and involves the use of rare-earth materials...and how quickly that deficit to ICE vehicles can be made depends on how the electricity powering the BEV was created.

Second, the comparison between the two technologies is arguably unfair seeing as one (BEVs) has benefited from a-lot of research (both time and money-wise) - from that perspective, I am actually disappointed with the rate of progress of BEVs, and believe that not only is hydrogen still in the early stages of research, but that it is capable of delivering some good results.

All that said, I think we should all keep in mind that anything and everything has its pros and cons, i.e. no technology is perfect.

The battery production does require a lot of mining of materials, but once those materials are in the battery they can be re-used. So at a certain point in the future we can expect the majority of new car batteries to come from recycled materials.

Secondly, it is wrong to say that fuel cells have only recently started development. Mercedes Benz have been experimenting with fuel cells since the 1990s. But they have never overcome their inherent problems to bring them properly to market. You cannot change the laws of physics.

Plugging a source of electricity directly into a battery is always going to be more efficient than using it to convert water into hydrogen, compressing that hydrogen, transporting that hydrogen, putting the hydrogen into a tank in a car, converting that hydrogen back into electricity, storing it momentarily in a battery, and using it to power an electric motor. Efficiency losses along the chain of events make the whole hydrogen thing a non-starter. Especially as fast charging tech and battery energy density is improving so rapidly.

While it's true that a large portion of a battery can be recycled, it is my understanding that the precious metals are not that easy to retrieve, and any materials that are not financially viable to be recycled by companies will not get recycled, so I'm not entirely sure if it will indeed be the case that "the majority of new car batteries [will] come from recycled materials".

Moreover, new battery technologies such as solid-state batteries are not that easy to recycle either. Another route is to re-purpose them to be used as electricity storage for buildings/homes...but there will be a limit to how much that can be done, and some are against that idea altogether.

Mentioning the recycling of batteries raises another point, namely the life of batteries. At the moment, manufacturers offer a warranty of maybe 8 years or so on the battery...at which point its efficiency will have dropped substantially. 8 years is not much; would it be economically viable to replace the battery in a car, or would it be deemed too expensive? In which case, a whole car would then need to be written off and recycled? Which also means that a new vehicle must be produced to replace it? To me, that seems like it could be quite environmentally damaging and wasteful (considering that you can't recycle 100% of a battery or car, and recycling in itself consumes energy too).

Regarding fuel cells, I did not say that they "only recently started development" - I said that it's "still in the early stages of research", which is a different matter; yes, hydrogen cells have long been in development, but not much time and money has actually been spent on them - far less than BEVs, certainly - so development has still been relatively minimal, and I would expect that several flaws can be eliminated or improved given time and investment on par with BEVs.

Lastly, there are losses accrued in the transport of electricity too (so no, unless you're generating electricity at home and plugging your car there, you are not plugging the source of electricity directly into a battery). Also, is it not possible that the production of hydrogen that can be used in vehicles can be improved (e.g. coming up with different processes, for which I think there actually is some ongoing research) given adequate development/research? The rate of progress in BEVs is (finally) gathering pace thanks to the sheer number of investment and companies working on them, but I wonder where hydrogen/fuel cells would be given similar R&D resources.

As with everything, economies of scale will be key. In the future as large amounts of batteries (finally) come to the end of their lives, recycling will ramp up, reducing costs, making the recycling of greater proportions cost effective.

The rate of advancement of BEVs in both energy density and charge rates has been huge over the last decade and will only continue. Hydrogen, despite huge investment from the likes of Toyota and Hyundai/Kia, has barely progressed by comparison.

Christian, I would suggest you go away and do as much research as you can. Once you can get your head around the whole process of producing and running various types of cars, then the advantage of the BEV becomes obvious. But you need to challenge every aspect of the process. There is a logic to why the entire industry is moving to BEVs, and to why Tesla is valued so highly by the market.