If you’re expecting the Victoria and Albert Museum’s latest headline exhibition, Cars: Accelerating the Modern World, to take an affectionate stroll through the 150-year history and progress of a much-loved four-wheeled transport device, you’d be dead wrong. It’s far better than that. It’s much closer to the truth that this superb display – detailed enough to provide two to four hours’ absorption for car lovers and neutrals alike – should be viewed as ‘The car and its influence, without prejudice’.

Which, when you think about it, places it in a space nobody in recent memory has attempted to fill. We live nowadays either with stentorian condemnations of cars that ignore their role in enabling progress on many other fronts (and probably helped their critics get to work that morning) or uncritical descriptions of enticing products, designed mostly to keep the wheels of commerce turning. Balance, away from Autocar, at least, is distinctly lacking.

Co-curators Brendan Cormier and Lizzie Bisley define their exhibition’s core purpose perfectly in the second sentence of an accompanying 220-page book you’d be crazy not to buy for £30 once you’ve seen the exhibition. The car, they say, has “stood for the possibility of a new way of living, while also being an active agent in shaping the systems, structures and images that have defined the modern world”. And the exhibition goes on to prove it.

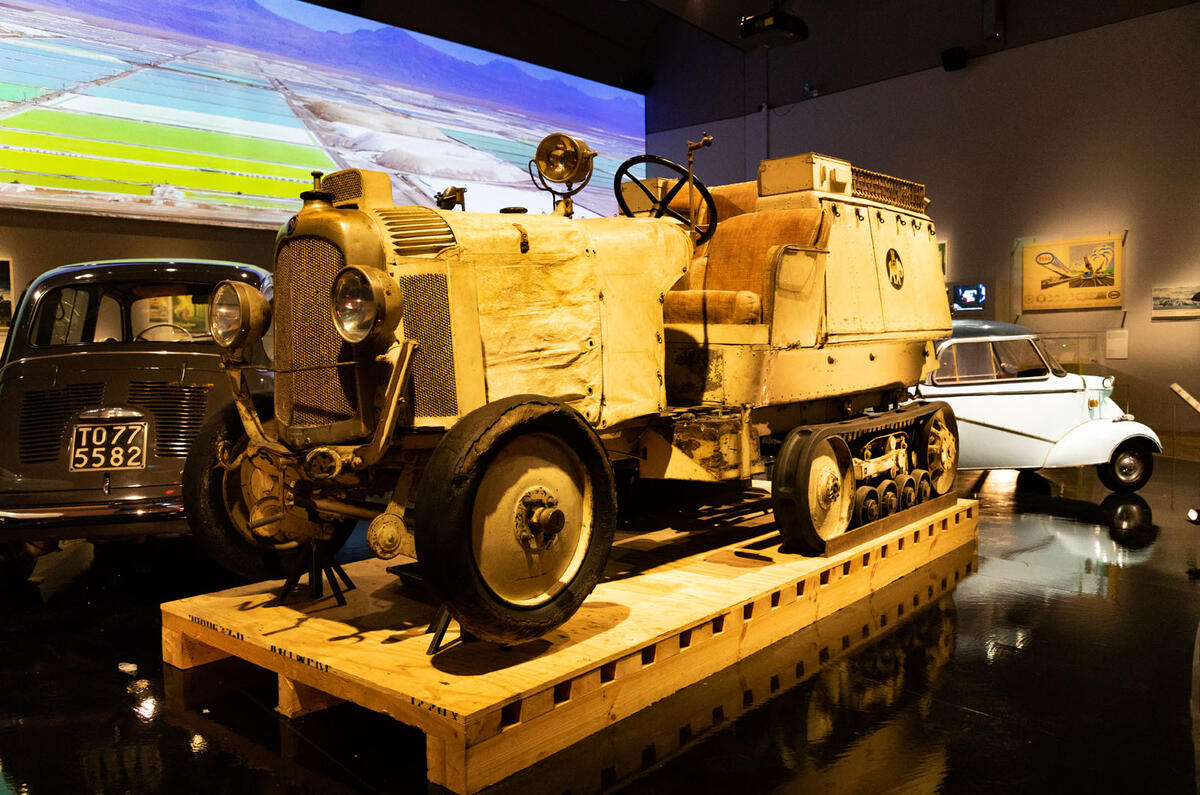

At Autocar, we already knew this was going to be an important V&A event, having previously attended a preview by Cormier, appropriately staged in the car-conscious Michelin Building just a few hundred yards from the great museum, in London’s South Kensington. Then, a day or two before the exhibition proper was to be declared open, we met Cormier again for an exclusive tour, during which he expanded on its thought-provoking aims and fascinating contents. “We have only 15 cars on display,” he explained, managing my expectations as we descended the imposing staircase into V&A’s basement gallery, “but we think they’re the right ones…”

The exhibition is arranged into three sections – Going Fast, Making More and Shaping Space – each of which encompasses appropriate smaller subjects that you encounter as you walk. The first object you see is one of General Motors’ enormously influential 1950s Firebird concept cars – a kind of jet fighter on wheels – that brought the dreams of science fiction to the simple optimistic post-WW2 era, especially in the US. Cormier calls this a kind of palate cleanser for people arriving at the exhibition, as well as a graphic illustration of how society began using cars to think about a post-war world.

Join the debate

Add your comment

Sounds enlightening

Nice write up Steve, always interesting to see things from a different or in this case unbiased view. Perhaps as car lovers we have a tendency to use rose tinted glasses where the car is concerned. Don't hang around if you want to see the exhibition though. It's only on until 19 April.