Next year, a team of British engineers will attempt to break the hallowed land speed record (LSR) in the South African desert. The target of their car, if you can describe the Bloodhound LSR as such, is 800mph.

At the wheel will be Andy Green, an RAF wing commander who flies the Eurofighter Typhoon – which uses the same very engine. Or, to be correct, the very same afterburning turbofan.

This is the Rolls-Royce EJ200, which provides around 9kN of thrust. It will be complemented by a peroxide-fuel monopropellant rocket, provided by ammunitions company Nammo.

Green has already held the LSR for 22 years, having become the first human to break the sound barrier on wheels – hitting an average top speed across the required bidrectional runs of 760.343mph – in Thrust SSC. This used a pair of older Rolls-Royce turbofans, one either side of the cockpit, rather than behind it as in the Bloodhound.

In earlier times, the LSR was broken far more frequently – often multiple times in a year. The rate of progress was incredible, too; just 49 years after the first recognised record of 39.24mph was set by an French aristocrat in his electric car, 400mph was exceeded for the first time.

In earlier times, the LSR was broken far more frequently – often multiple times in a year. The rate of progress was incredible, too; just 49 years after the first recognised record of 39.24mph was set by an French aristocrat in his electric car, 400mph was exceeded for the first time.

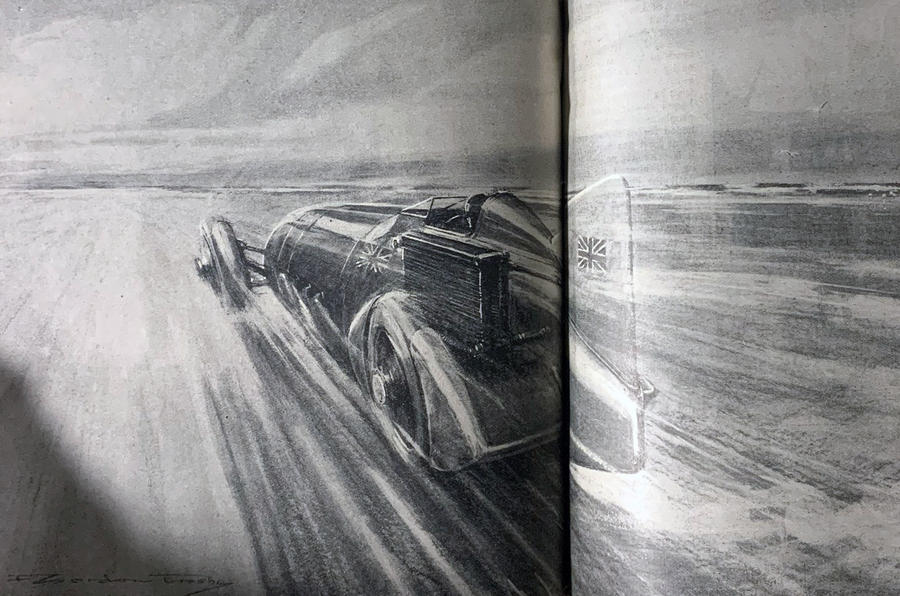

One of the most fervent periods of competition in LSR history was the 1920s and 1930s, when Malcolm Campbell and Henry Segrave of Britain and Ray Keech and Frank Lockhart of the US continually sought to outdo one another, initially down Daytona Beach and then on the Bonneville Salt Flats.

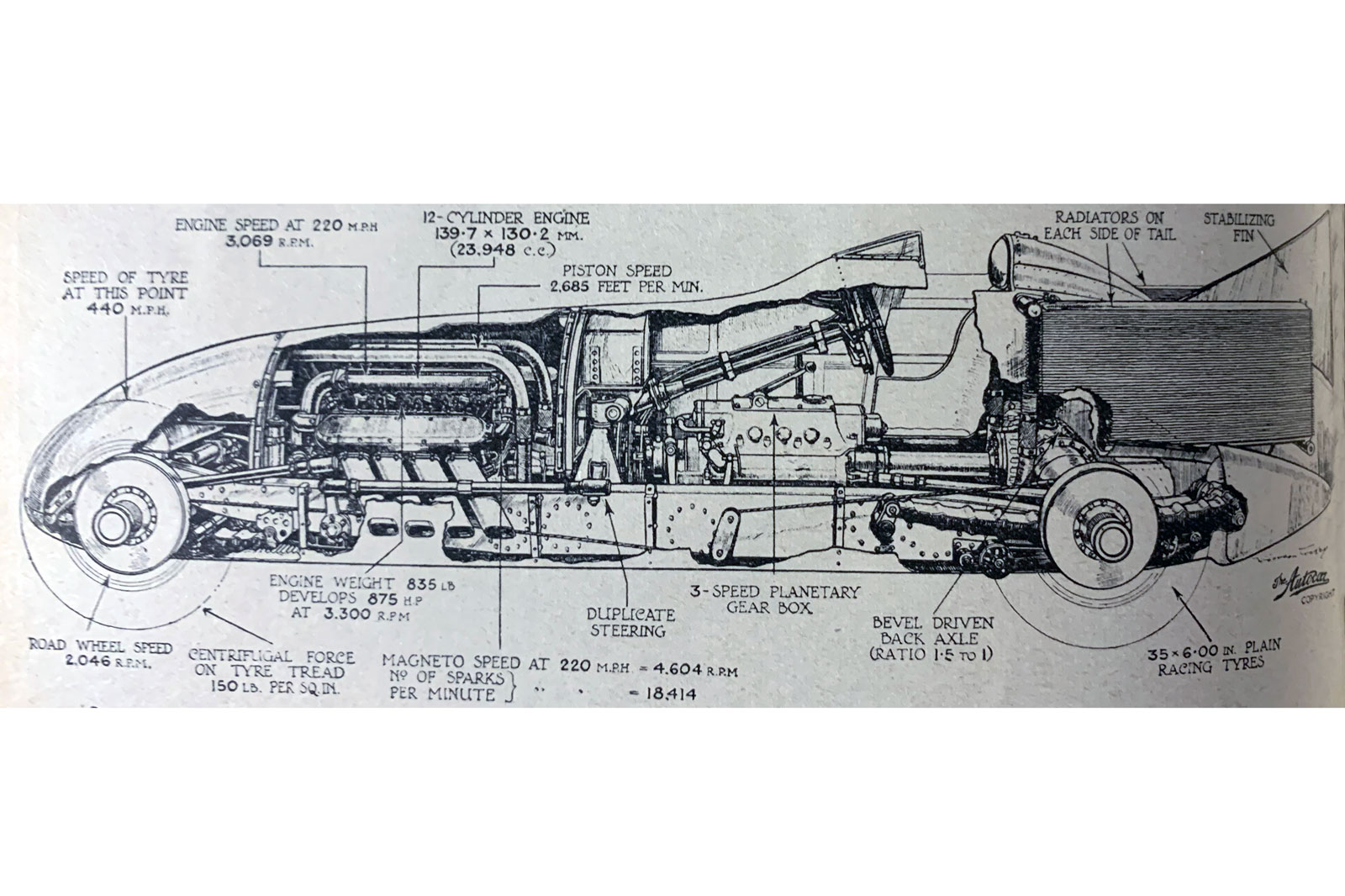

In late February 1928, Autocar reported on the success of Campbell – aready his fifth – in reclaiming the accolade from Segrave, who had averaged 203mph the previous March. The Balitmore-born Irishman had done so in the Mystery (more popularly known as the Slug), which had been built by Wolverhampton's Sunbeam company, using two 22.4-litre V12 aircraft engines to produce 900bhp.

This might have been true; rival Segrave recorded 231.446mph in 1929, also using the Lion engine in his Golden Arrow. For the next iteration of the Blue Bird, Campbell would employ a supercharger, more than tripling its power to 1450hp. The final iteration, Bluebird V, would take Campbell to his final LSR of 301.129mph, thanks to 2300hp.

This might have been true; rival Segrave recorded 231.446mph in 1929, also using the Lion engine in his Golden Arrow. For the next iteration of the Blue Bird, Campbell would employ a supercharger, more than tripling its power to 1450hp. The final iteration, Bluebird V, would take Campbell to his final LSR of 301.129mph, thanks to 2300hp.

Add your comment