In 1910, eminent French car maker De Dion Bouton introduced what would become the first mass-produced eight-cylinder engine.

It was certainly not the first to use a V8. In fact, the first was the Rolls-Royce V-8 of 1905, which was intended to steal sales in towns from electric cars (ironic, no?) but was canned after just three examples were produced. And the first V8 for any application was introduced the year before, by the French Antoinette company, for use in aeroplanes. There was even a straight eight back in 1902.

As the De Dion Bouton models gained popularity, Autocar in 1913 explained the benefits of the V8 and why it seemed like the optimum engine configuration for the future.

"Everyone will remember what a tremendous volume of ink was spread over the subject when the six-cylinder engine first came amongst us," began our man W.G. Aston, "and definitely marked a new epoch.

"Now there are good grounds for supposing that another such epoch will be marked in the comparatively near future by the eight-cylinder engine, which is even more superior to the six-cylinder than the six-cylinder is to the four-cylinder.

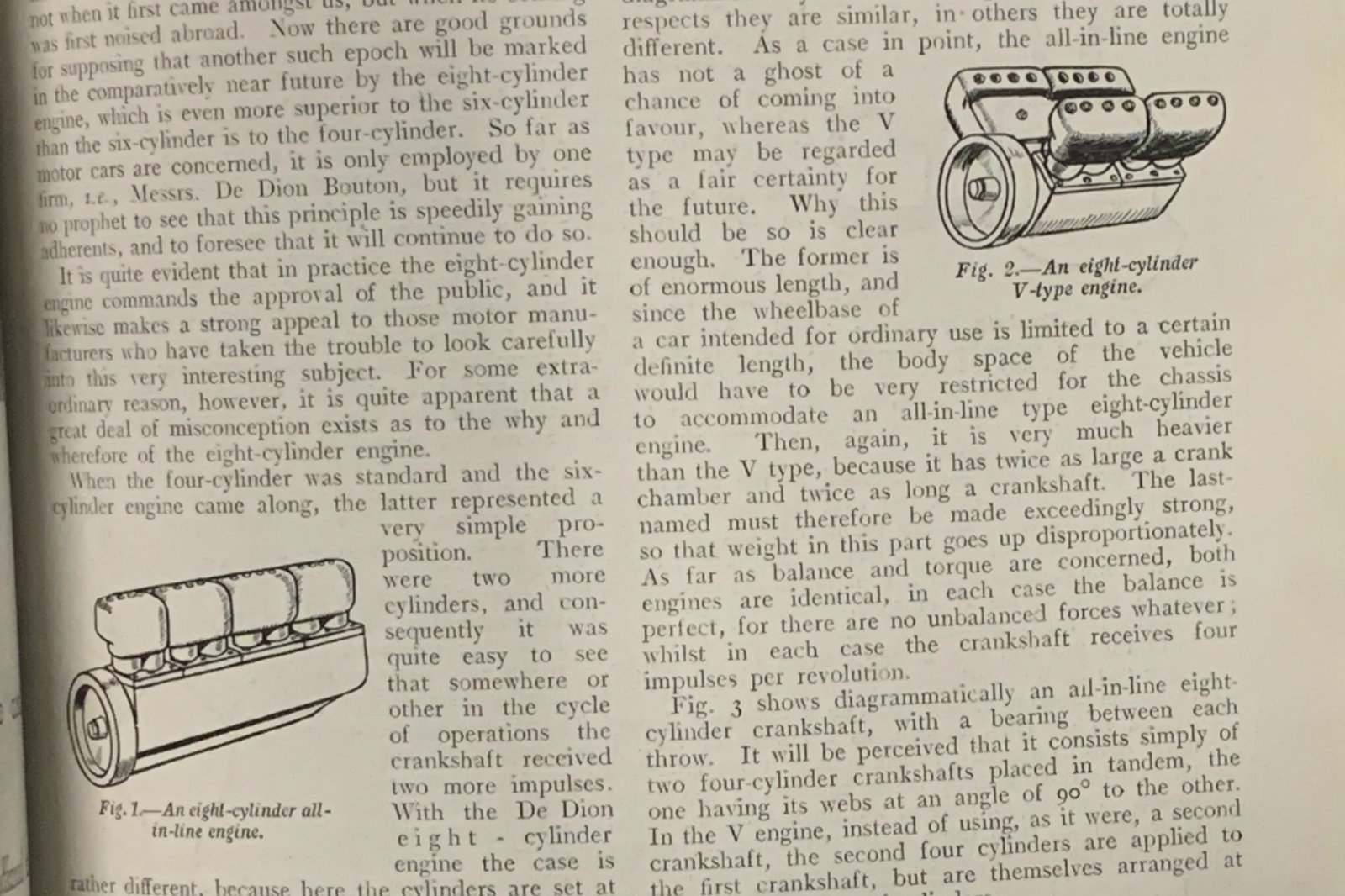

"When the four-cylinder was standard and the six-cylinder came along, the latter represented a very simple proposition. There were two more cylinders, and consequently it was easy to see that somewhere or other in the cycle of operations the crankshaft received two more impulses. With the eight-cylinder engine the case is rather different, because here the cylinders are set at an angle with one another, and not all in a row along the crank chamber."

Because the V8 engine thus looked like a pair of separate four-cylinder engines bolted together, many people assumed that it would merely operate in the same manner but with twice the power. Not so.

Add your comment