We’re carrying on. Of course we are; we always have. Autocar has witnessed a lot of world events and disasters during its 125-year life, but we’ve continued to produce a weekly magazine throughout.

The Autocar was just a few years old when the Second Boer War broke out, but a war being fought in South Africa didn’t have much of an effect back home. Anyway, there were only six privately owned cars in Britain when the magazine was first published, and I doubt there were that many more while the Boers were being beaten.

Only twice in its long history has Autocar not made it onto the shelves. There may be a few readers who were alive during the first occasion but probably none who will remember it or whose own reading was interrupted. Guessed it? It was during May 1926, when the General Strike brought the country to a standstill. Still the only general strike ever called in the UK, it ran for only nine days until the Trades Union Congress and Stanley Baldwin’s government managed to come to an agreement. Three issues of The Autocar were lost.

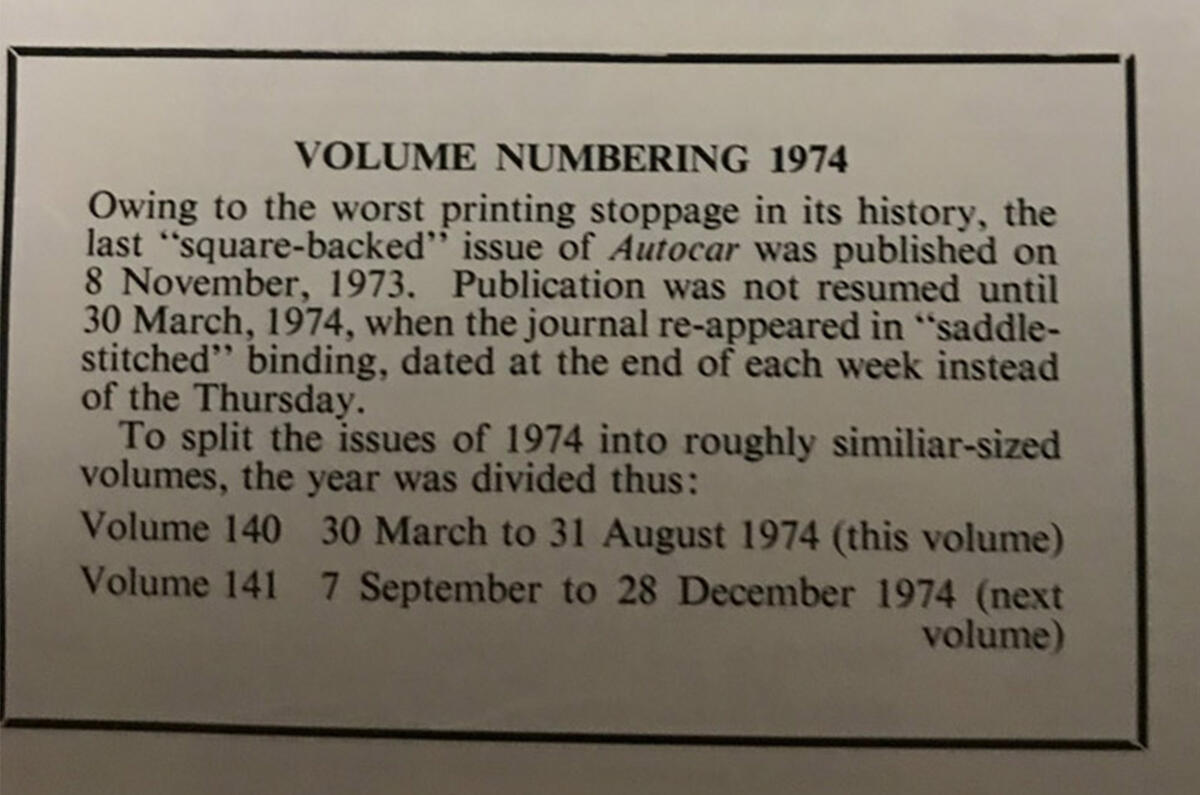

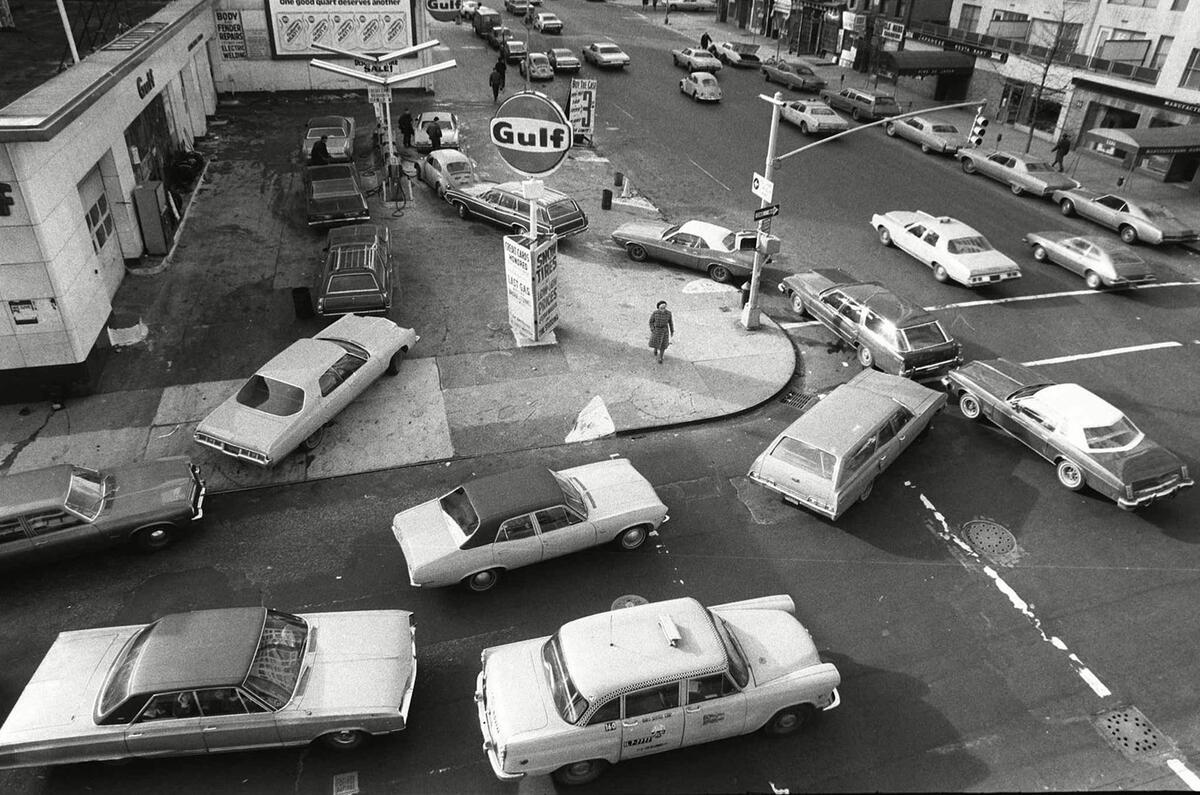

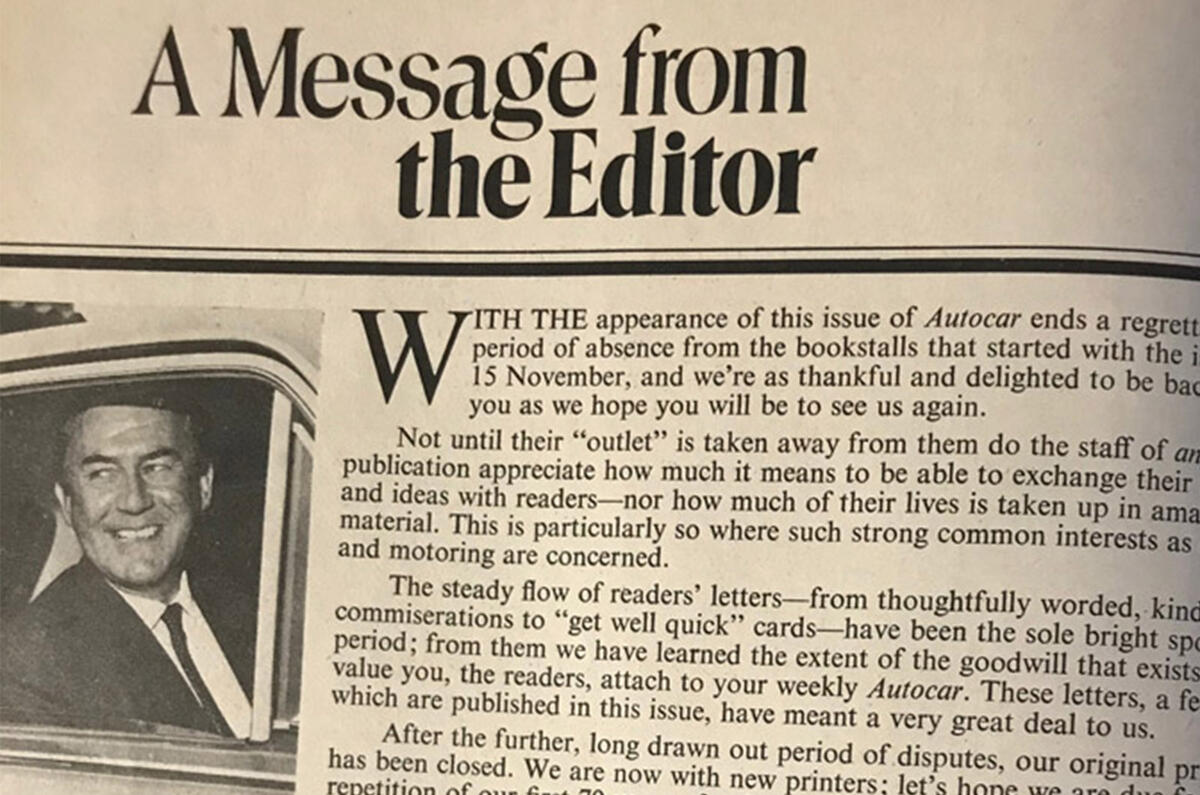

The second occasion many of us were around for, and I’m sure a great number of you remember being starved of your favourite motoring publication. We’re talking about the 1973 fuel crisis and the three-day week. Power cuts, sharing baths and, as remembered fondly by this writer, school lessons by candlelight. The miners were on strike and so too were the printers. The latter caused the longest absence from the shelves in Autocar’s history: an outage that ran from 15 November 1973 until 23 March 1974. The print unions had achieved something neither Kaiser Wilhelm II nor Adolf Hitler could.

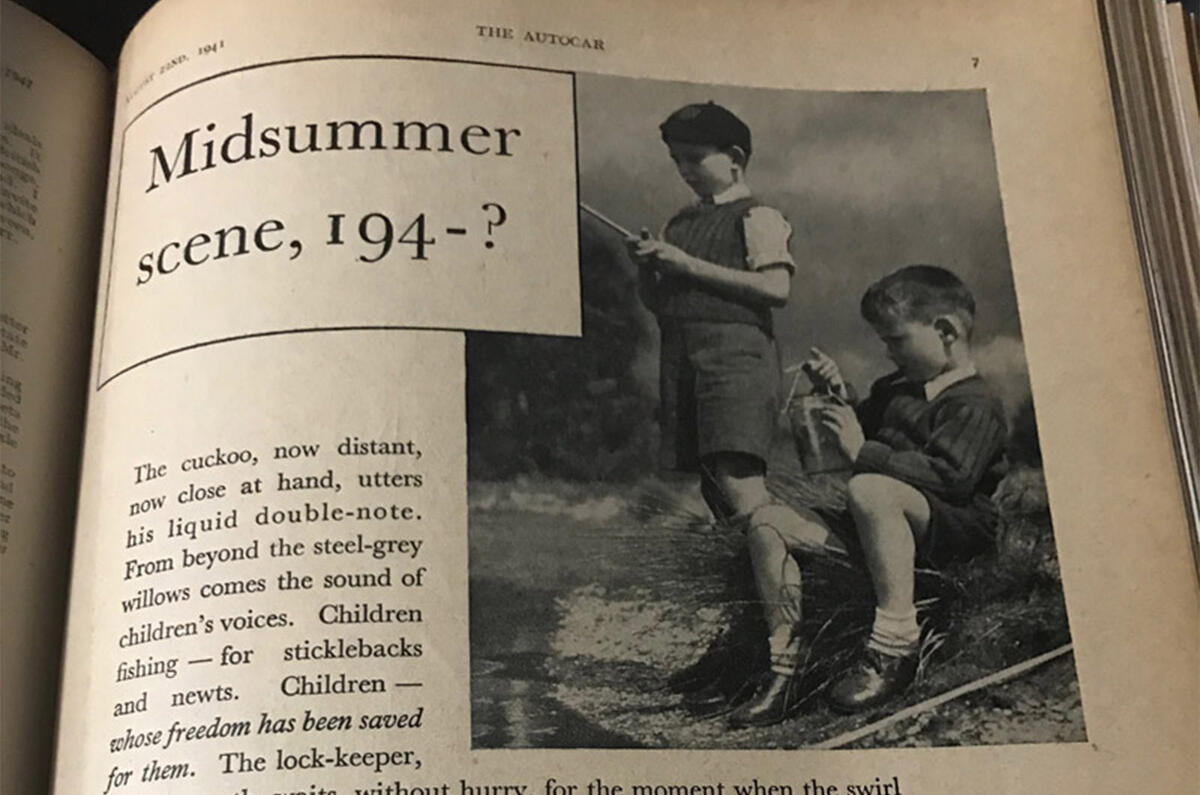

It’s amazing that not a single issue was missed during either the First or Second World Wars. Paper could have been a problem, certainly in WW2, because it was strictly rationed, but titles such as The Autocar and Motor Sport were considered important for keeping up morale (hopefully we’re doing the same today) so were allowed to keep printing.

The demand was certainly there because, in times of stress and deprivation, one turns to hobbies and the hope of reconnecting with them when things are back to normal. Certainly that was the philosophy behind the Muhlberg Motor Club’s motoring magazine, The Flywheel, which was produced from 1944-45 by the inmates of Stalag IV-B.

At the beginning of both world wars, not much changed. The first was famously anticipated to be over by Christmas and the second began as the ‘phoney war’. Eventually both became terrifically serious and impinged on all aspects of life, including motoring.

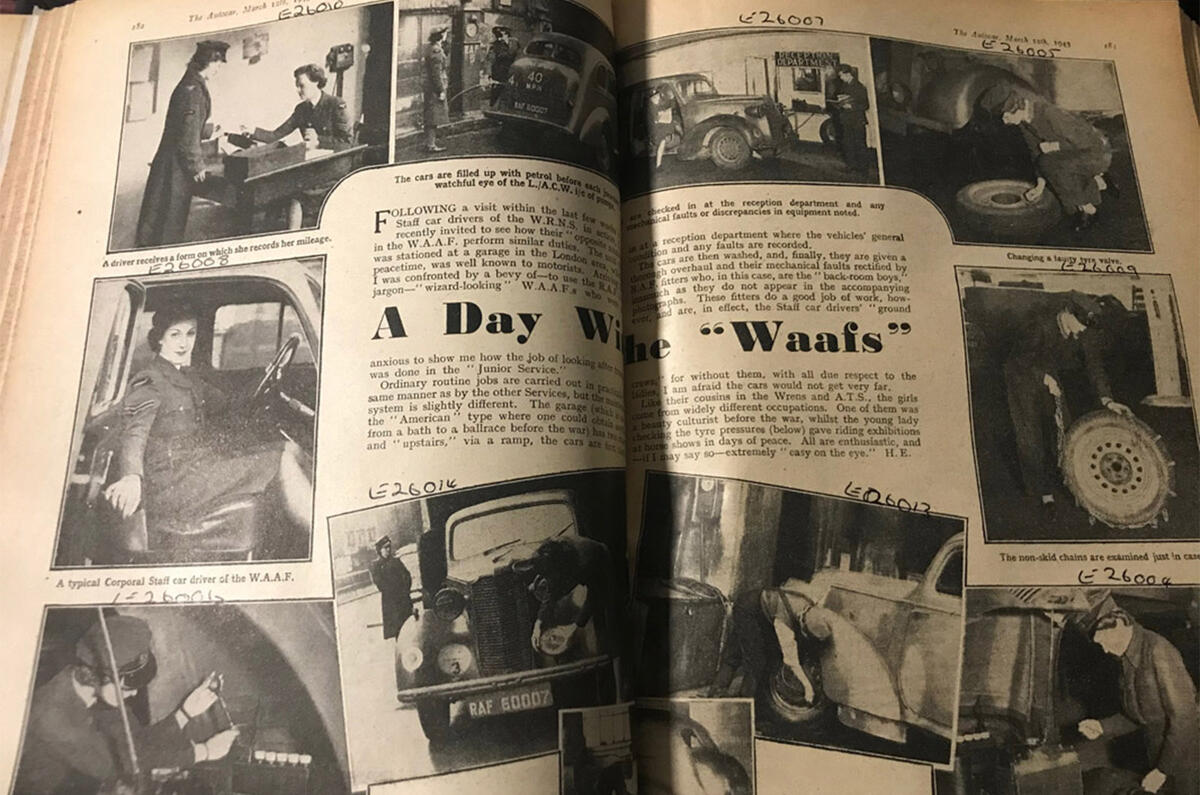

There are comparisons to be made between wartime life and the current coronavirus crisis. Many aren’t relevant to a motoring magazine, but the one thing that we who write for Autocar share with our forebears is a dwindling bank of new car features, whether it be first drives or group tests. All the UK importers have locked up their fleets of cars and all launch events have been cancelled. Soon we will have covered all the new cars that we have driven in the past months. What will we write about then? And about what did the staff at The Autocar write when they were in a similar position?

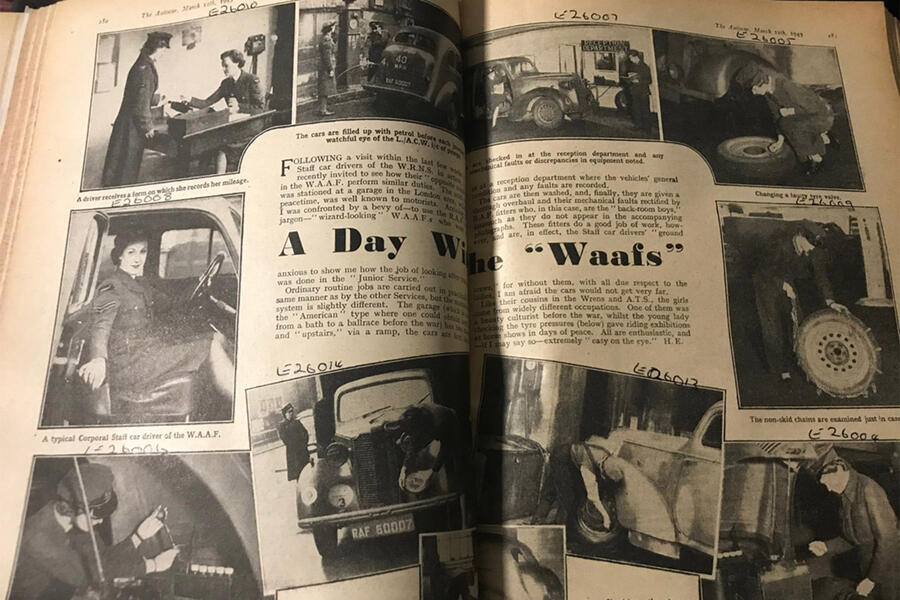

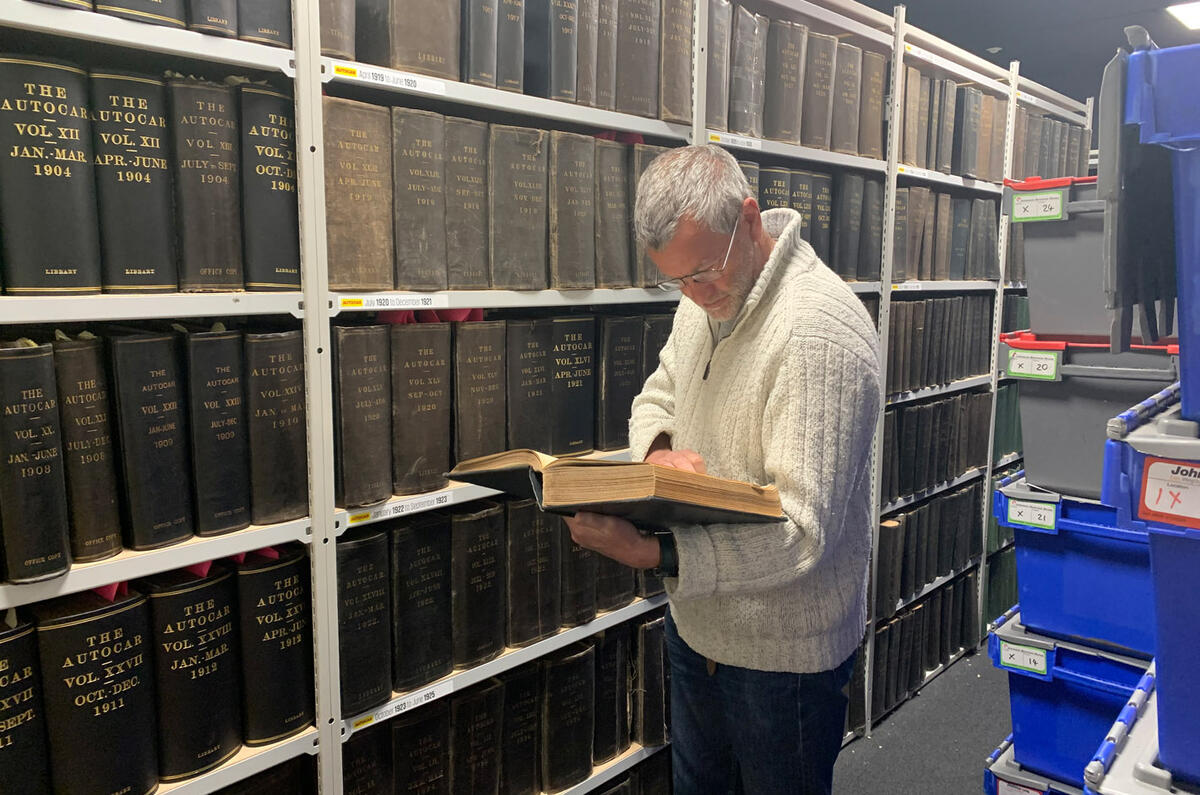

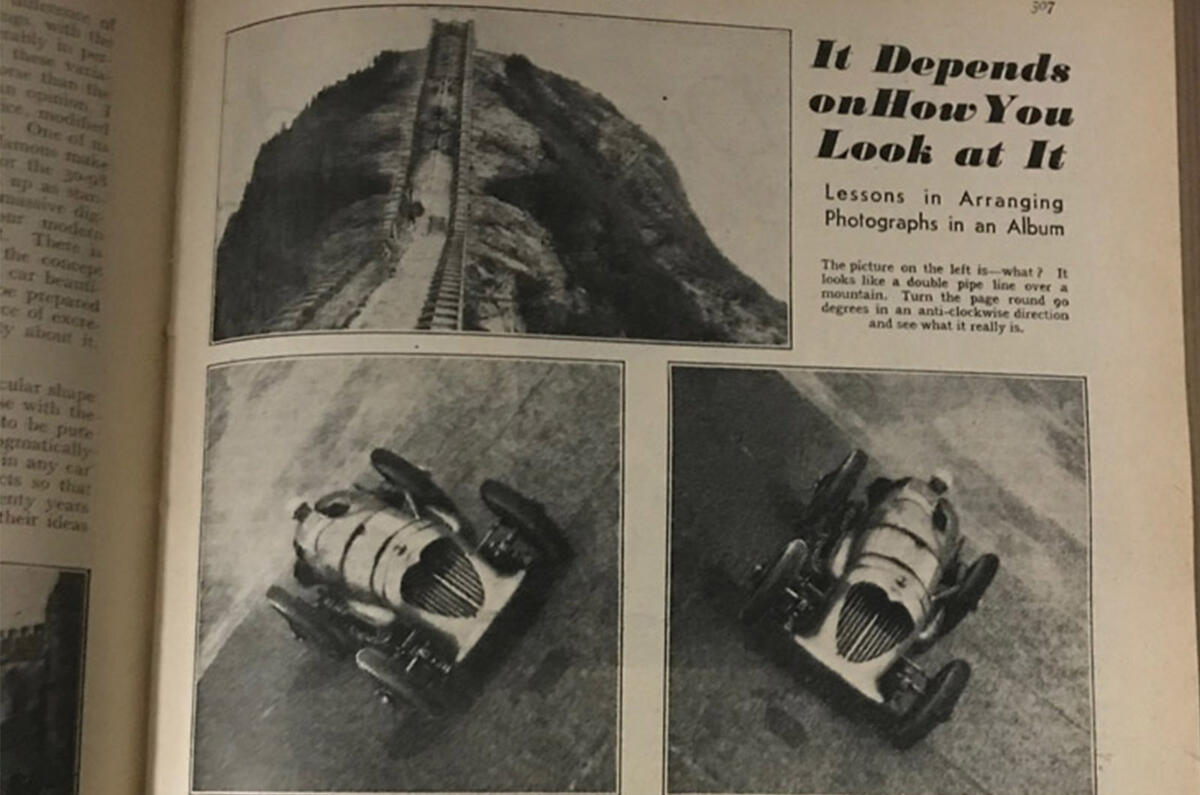

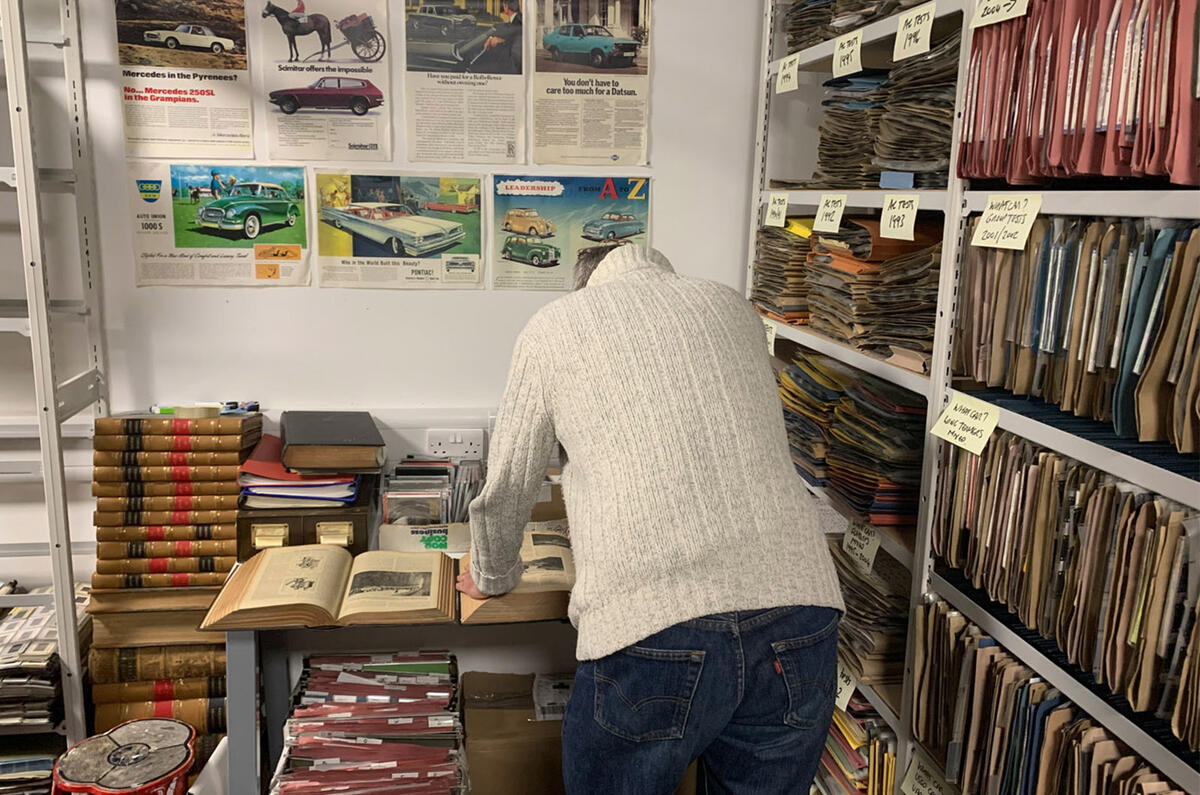

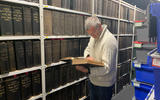

Just before the lockdown, I spent a very enjoyable afternoon in the Haymarket basement, looking through the company’s complete collection of the magazine from 1895 to the present. There’s some great stuff in there. Not just entertaining pieces but also thought-provoking and provocative articles on subjects not entirely irrelevant today.

There’s a great editorial that was published on 6 May 1916. It starts with the brave statement that Germany could have staved off the war and instead beaten us commercially and industrially by simply continuing down the path on which it was already travelling.

The editor bemoans that the fact that we had become too reliant on imported and foreign parts for our cars, mentioning magnetos in particular. He goes on to suggest that, after the war is over, we in Britain should make our own fuel from the by-products of agriculture so that we will no longer be beholden to foreign suppliers, and equally boldly points out that Germany is already doing just such a thing.

The Autocar also played its part in the war effort, as a short news piece in the 10 November 1917 issue shows. The week before, we had run an article on The Red Cross School of Motor Mechanics that had been set up in Vevey, Switzerland, for prisoners of war interned in the country. The editor had pointed out the great work the school was doing to help the servicemen learn skills that would be useful to them in peacetime. He had also asked readers to contribute to the running of the school and a week later had received several hundred pounds. It’s good to note that the then publishers of The Autocar, Iliffe & Sons, had themselves put in £105.

By the time the country was at war again, the motoring world had changed dramatically, even though just 20 years had passed. Private car ownership was far more common and there had been two decades of fantastic motorsport. There were more cars and there were better and more exciting cars.

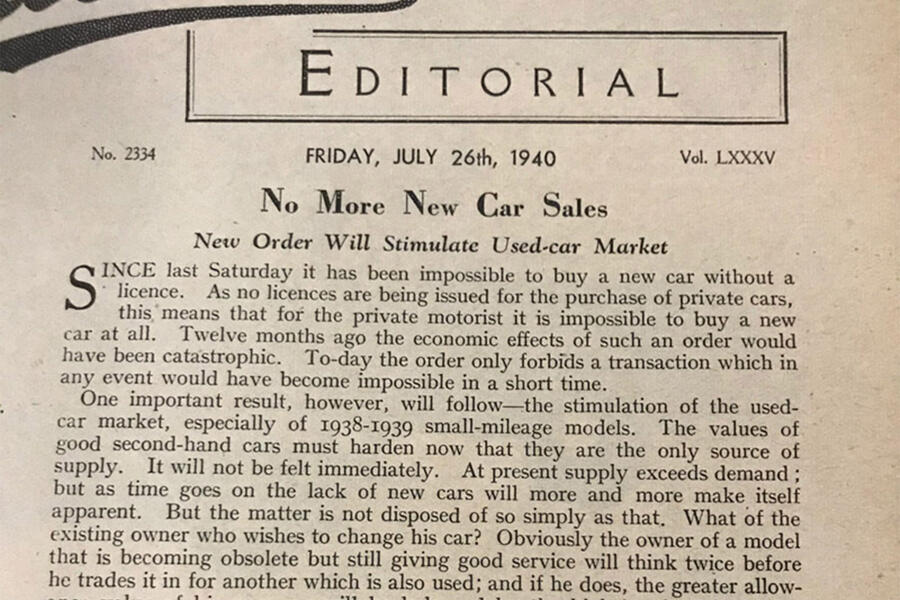

But, as announced in an editorial in the front of the issue dated 26 July 1940, right in the middle of the Battle of Britain, there were no new cars. “Since last Saturday,” wrote the editor, “it has been impossible to buy a new car without a licence.” Below this piece, we noted that 10 times more people were killed on the roads in June than were killed by air raids. That ratio would be modified that autumn by the start of the Blitz.

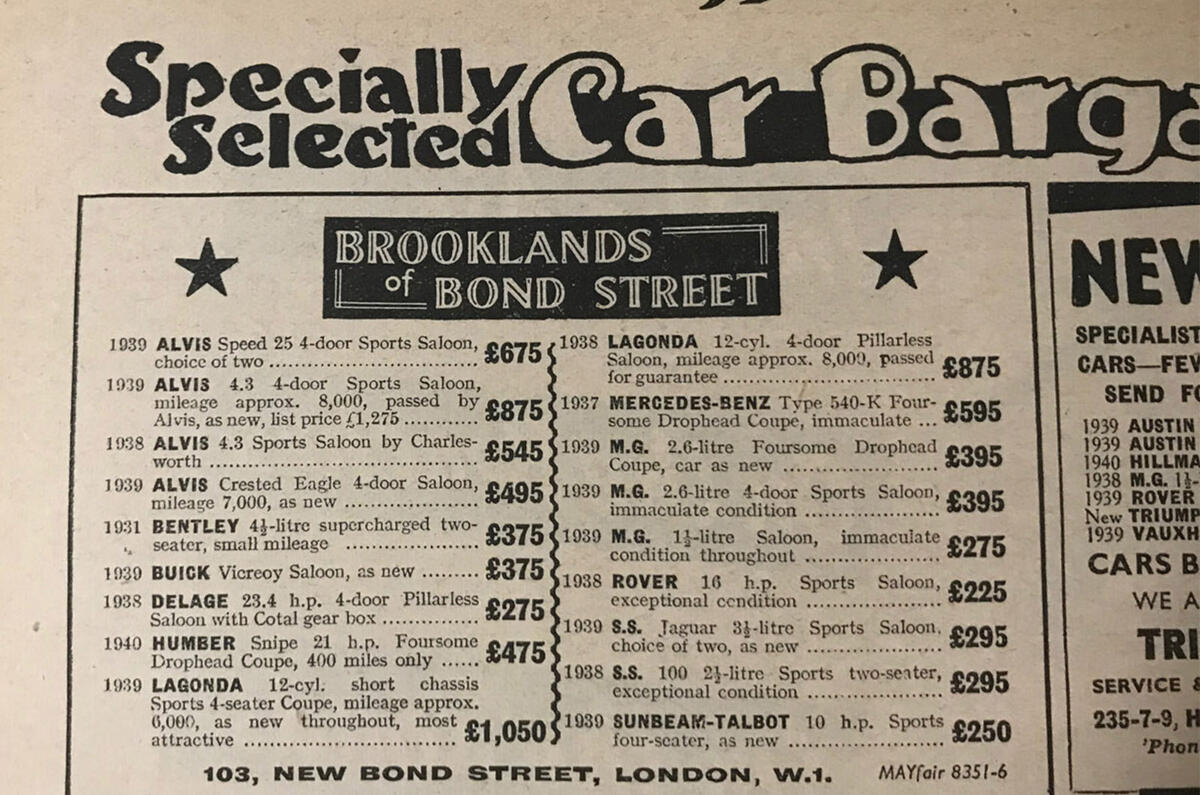

While buying a new car was out of the question, there was a plentiful supply of used cars available. The Autocar’s classified pages, certainly in the early part of the war, were far better populated than petrol rationing would have you expect.

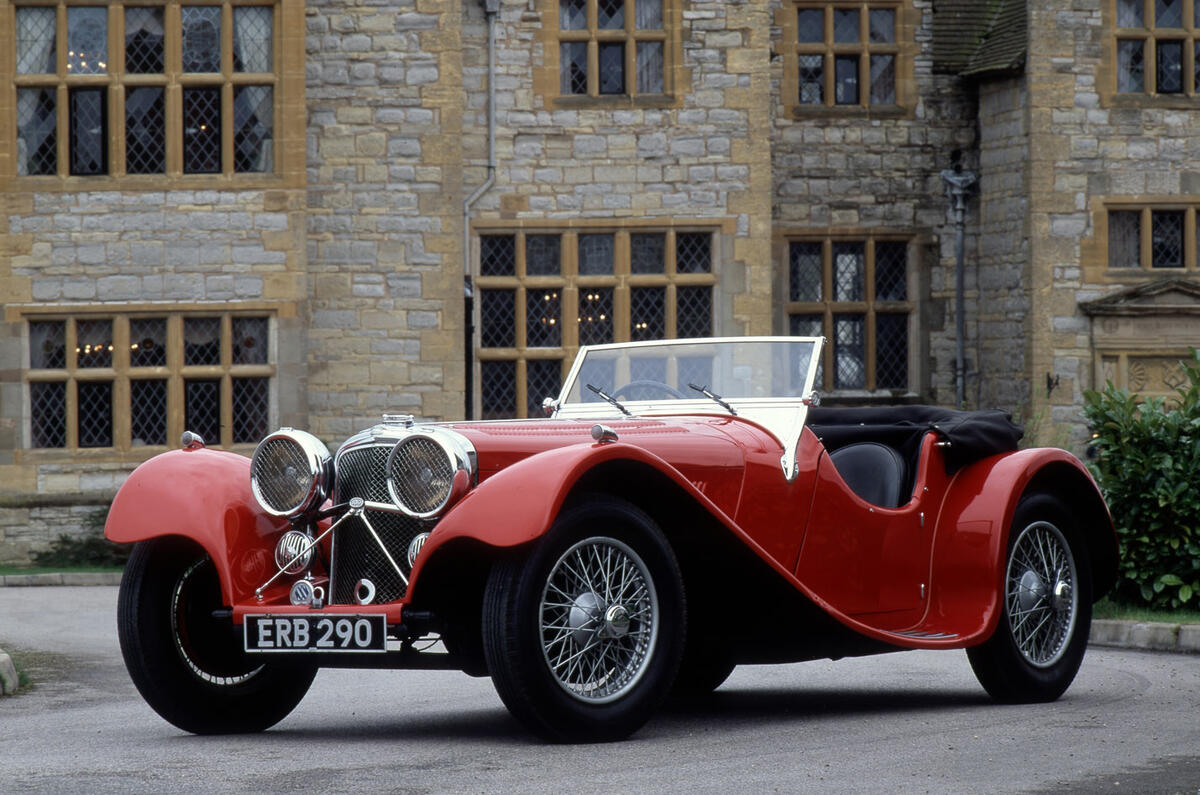

My nose would have been firmly pressed against the window of Brooklands of Bond Street in London, whose September 1940 advertisement contained such mouthwatering machines as a nearly new Lagonda V12 coupé for £1050 (roughly a seventh of the price of a new Supermarine Spitfire) and, if its country of birth didn’t bother you, a 1937 Mercedes-Benz 540K for £595. For the RAF fighter pilot, it surely would have had to be an SS Jaguar 100 two-seater at £295.

The Autocar didn’t seem to have much trouble sourcing writers for its wartime articles. Here’s a name that may well be familiar to you (no, not Steve Cropley): Denis Jenkinson. The legendary Jenks was working as an engineer at the Royal Aircraft Establishment in Farnborough alongside the equally legendary Motor Sport editor Bill Boddy, who was busy writing flight manuals.

Jenkinson contributed to the 28 March 1941 issue a fascinating four-pager on the relative performance of well-known competition machines – a feature that is timeless and would be fascinating to replicate in 2020.

As for racing itself, there of course wasn’t any in Europe. The Indianapolis 500 was run in 1940 and 1941 but then stopped after the US entered the war. The Autocar didn’t forget about motorsport for the duration and instead ran many articles that looked back at some of the great races from the past decades.

Prince Chula of Thailand, cousin of the famous racing driver Prince Bira, wrote several such emotive pieces, including a history of The British Empire Trophy for 4 April 1941.

There was never a shortage of readers’ views, either. Here’s a cracker from John Bartlett of North London, which begins in the fashion that many of your letters still do.

“Having been a reader of The Autocar since 1925, when I was 11 years of age, I have written at different periods in your correspondence columns. However, due to the Dunkirk business, I have returned to civil life minus my right leg but am managing on a metal one.”

Mr Bartlett then goes on to describe the arrangement and operation of the disabled driving controls on his Austin Seven that he designed and manufactured himself.

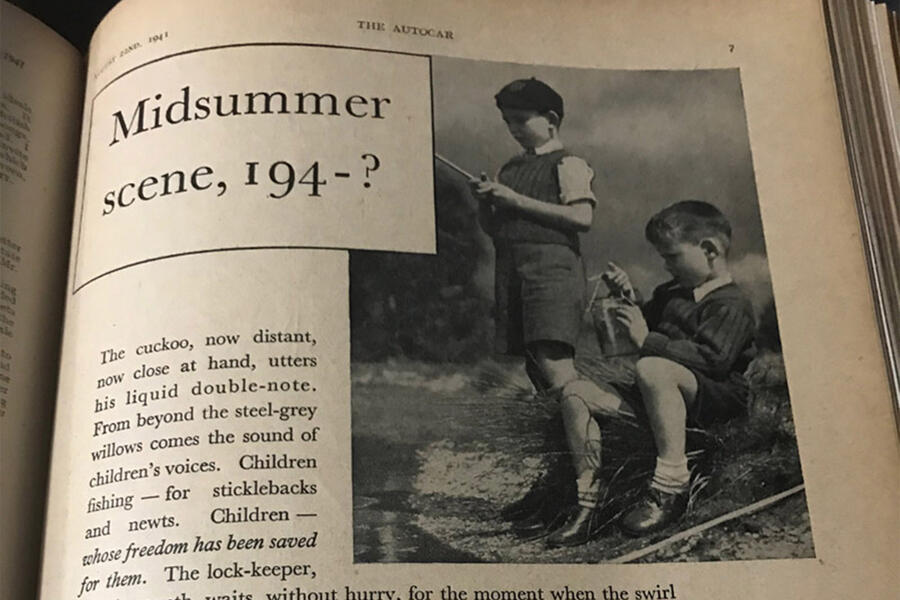

There was a strong feeling of optimism throughout the whole war, even during the darkest periods, that things would go back to normal after an Allied victory. Towards the end, when this was on the horizon, The Autocar busied itself with practical matters, such as how to recommission your car.

Even as far back as February 1943, we had been considering the problem of tyres on cars that had been laid up being perished by the time the war was over. The Autocar, concerned that post-war new car production would eat up the supply of fresh tyres, urged the authorities to make sure owners of old cars were also supplied.

By 1945, the talk was of the sort of new cars that would be made and how the huge improvements in metallurgy, manufacturing and technology that had been learned in the development and building of war machines would benefit cars. There was excitement also about the restarting of motorsport and the very accurate prediction that the perimeter roads of RAF airfields could be used as racing circuits.

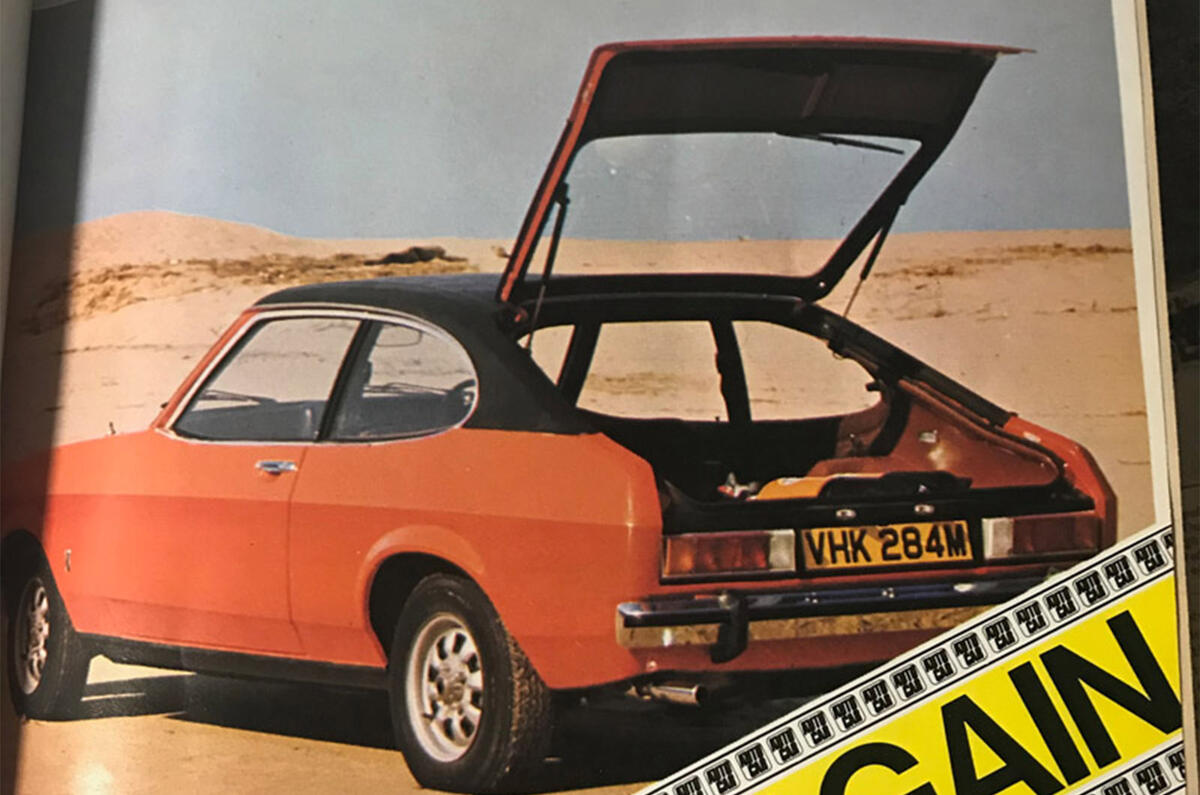

We live in very different times, of course, and are facing different issues with this pandemic. But some things are the same: my colleagues are still beavering away to produce a magazine in challenging conditions, while we’re all looking forward to getting out on the road again and to enjoying events like the postponed Goodwood Festival of Speed.

Stay calm and publish. That’s the Autocar motto.

READ MORE

Coronavirus: What motorists need to know

Coronavirus and the car world: sales slump across Europe

Vauxhall boss: coronavirus will change car buying for good

Join the debate

Add your comment

Autocar magazine unavailable

That headline should wake everyone up.

I have been purchasing the Autocar magazine for many years over here in Dublin, Ireland since the 1980's. Not every week, you understand. I simply head down to my local magazine store and there it is - always placed on the magazine shelf of my local Spar.

But since the corona virus outbreak the magazine is totally unavailable - much to my great disappointment. We have not had a copy of it since the 3rd week of March 2020. All Eason's stores are closed.

What I miss most of all is the 8 page road tests.

Safe driving.

Flt 158

An aside..

I read the Autocar magazine too, for free, well, I used to, because it was in the local Library, now, the aside, I also have a monthly subscription to Topgear Magazine, they contacted me by letter to say , if the could not deliver for whatever just now, they'd sent me an E-copy online for nothing, now, I wonder.

What of Motor magazine?

It is great to read this Autocar history. But is there anything of the 'other half' of the magazine? I am, of course, referring to the history of 'Motor' magazine, the erstwhile competitor to Autocar every week from Jan 28 1903 until the great merger in 1988. Indeed, the combined entity was titled 'Autocar & Motor' from Sept 7 1988 to Sept 21 1994, after which the name reverted to Autocar again. What has happened to the Motor archives?

Isn't it obvious?

Thanks Col

Great article, very interesting to see the archives