A car's design is about so much more than how it looks. Executed well, design forms an intrinsic part of the entire package, in a ground-up process. An example is the new Gordon Murray Automotive T50 supercar, which, it is claimed, will be the lightest V12 supercar ever, at just 980kg. The V12 produces 650bhp and a quick sum reveals a power-to-weight ratio of 663bhp per tonne. But that’s not the way one of the industry’s most innovative thinkers approaches the task of reducing weight. Murray says it’s the other way around that counts: weight to power.

His reasoning goes like this. Calculating weight to power reveals that every 100bhp developed by the T50’s V12 has to move 150kg of weight. By comparison, with a typical supercar (which, according to Murray, weighs on average 1460kg), 100bhp is moving 210kg, an increase of 40%. His weight-saving philosophy makes a lot of sense, painting a much clearer picture of the work the powertrain has to do. Weight is worthy of consideration right from the earliest concepts, rather than designing a car and adding lightweight features and materials after the fact.

The average supercar would need an additional 300bhp to match the T50’s weight and power relationship and that would lead to a vicious circle of increasing weight, cost and complexity (bigger, heavier brakes, larger wheels and tyres, heavier chassis elements) rather than a virtuous circle of shedding all three.

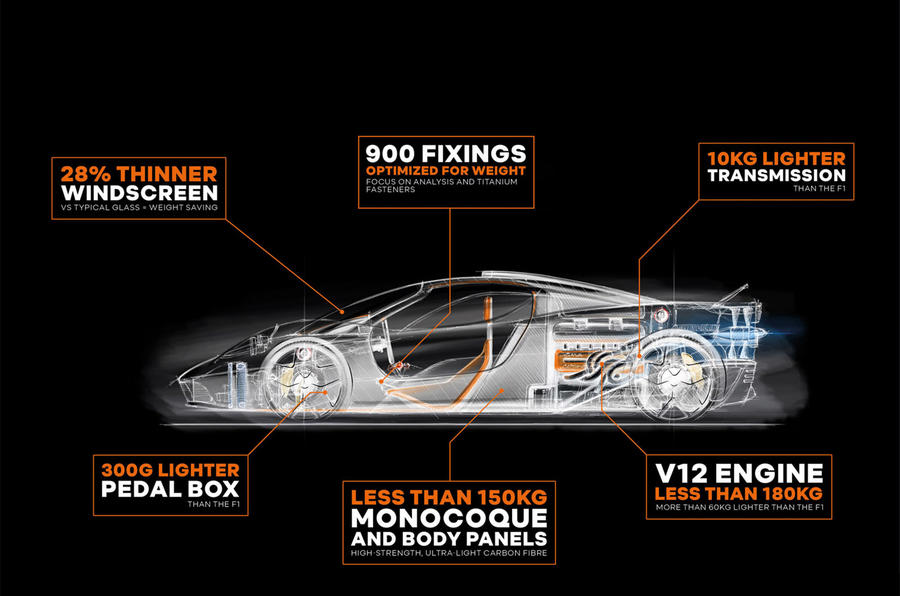

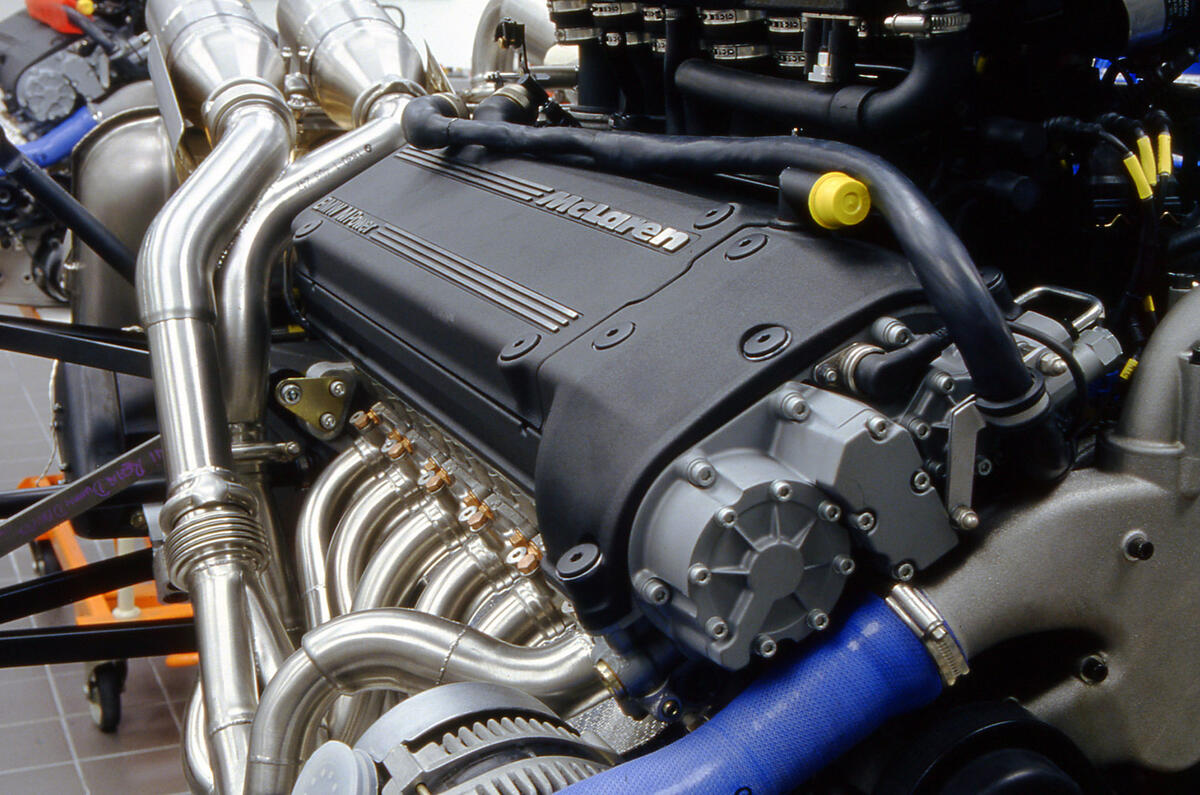

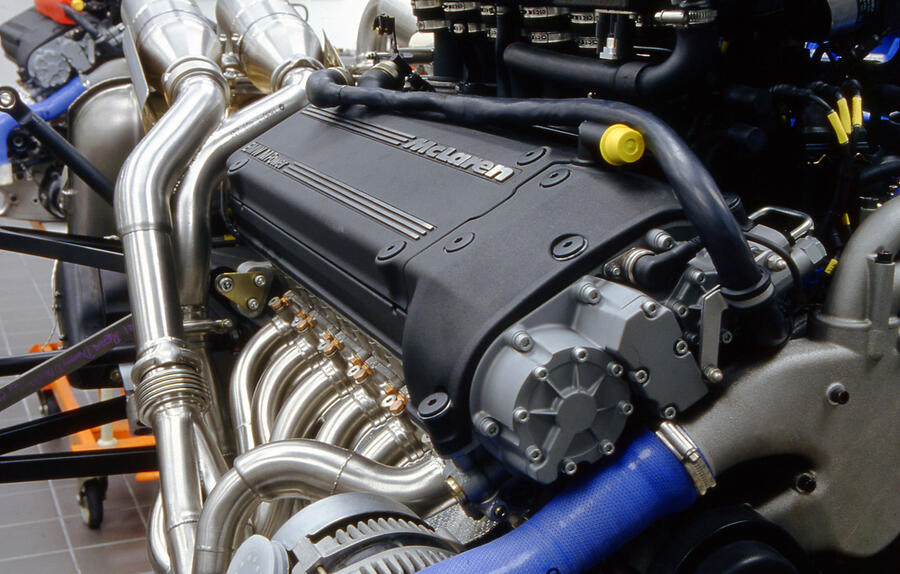

As a result of this ground-up devotion to weight saving, the T50’s full-carbonfibre monocoque with all body panels weighs 150kg, the driver’s seat 7kg and the two passenger seats either side of it 3kg each. That’s 13kg for all three seats. The GMA-Cosworth V12 weighs a modest 180kg, 60kg lighter than the mighty BMW S70/2 V12 of the McLaren F1, yet is more powerful.

A weekly ‘weight watchers’ meeting by the GMA team keeps an eye on the weight of components right down to the last nut, bolt and washer rather than making do with generic items that are always heavier than they need to be, even if only by a couple of grams each. It’s an approach reminiscent of that taken by Ferdinand Piëch and the legendary, ultra-lightweight Porsche 908/2 sports racing car in which some bolts were made from titanium, machined to the exact length required and drilled through the centre to save every scrap of weight.

Although the T50 is massively more robust than the notoriously fragile 908/2, the approach taken to reducing weight is just as scrupulous. Minutely detailed calculations were made to establish the length and diameter needed for each of the 900 bolts, given the forces each will take.

Why does this matter so much? However clever engineers may be at disguising the weight of cars (most of which are way heavier today than their ancestors) with clever chassis design, advanced steering technology and more power and torque, a lighter car will always be dynamically superior, more agile and more fun to drive at any speed.

Join the debate

Add your comment

Been here before

See Caterham (Lotus) 7, original Lotus Elite, Elan etc.

Wasn't it he who said 'there's never anything new in car design,you just take old ideas and improve them'.

If you stand on your head will it go faster?

Focusing on reducing weight makes sense. Claiming there is a difference between power to weight and weight to power is nonsense. I suspect that this was a figure of speech that has been taken a little too literally.

And your contribution was...

Anyone care to list their famous engineering milestones?

Thought not.