We have heard a lot about electric boosting (e-boosting) of diesel engines in the past few years. Several premium brands now use this in conjunction with conventional turbochargers to improve response at low revs and low power, with the conventional turbo taking over at higher power to pump enough air into the engine.

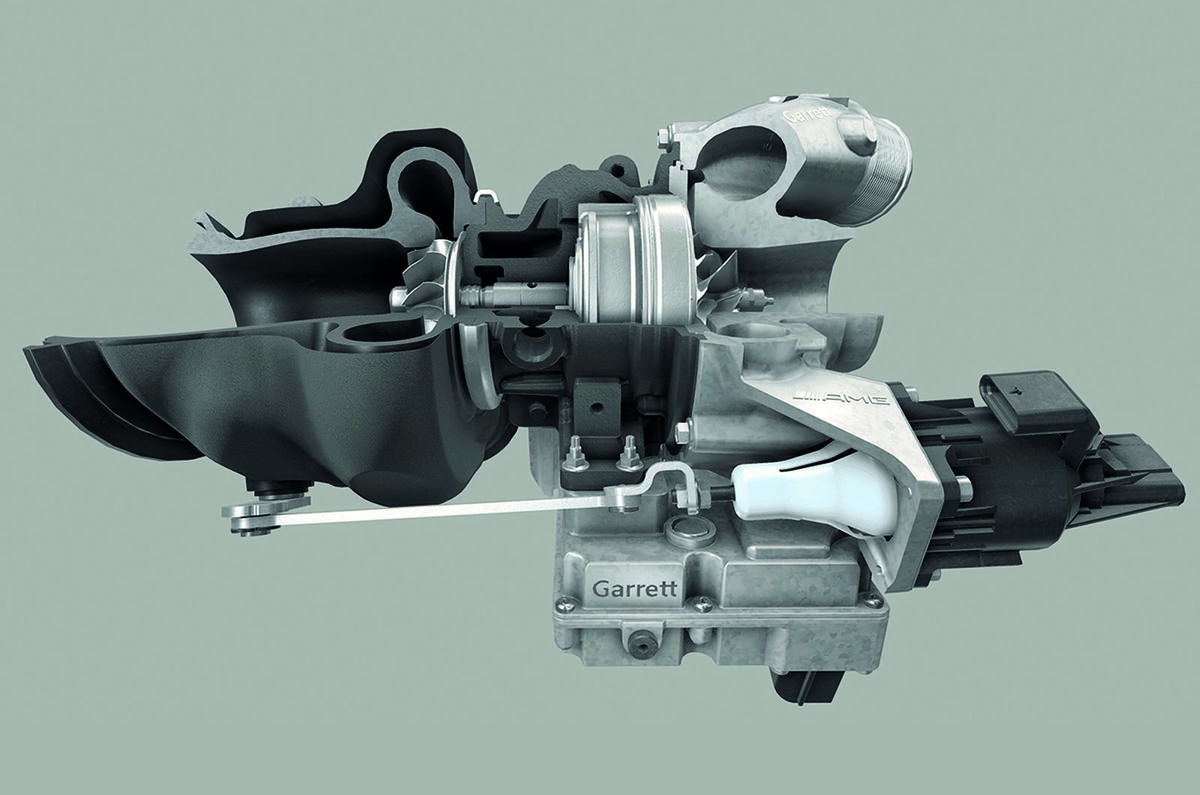

The latest, though, and touted as one way of helping engines to meet future emissions legislation, is the e-turbocharger. This is already used in Formula 1 and is being developed for road use by Mercedes-AMG together with turbo maker Garrett Motion.

E-boosters (or electric superchargers) and e-turbochargers are quite different animals. A conventional turbo is driven by exhaust-gas energy and consists of two main components: a gas-driven turbine and a compressor that actually does the pressurising of the engine intake air.

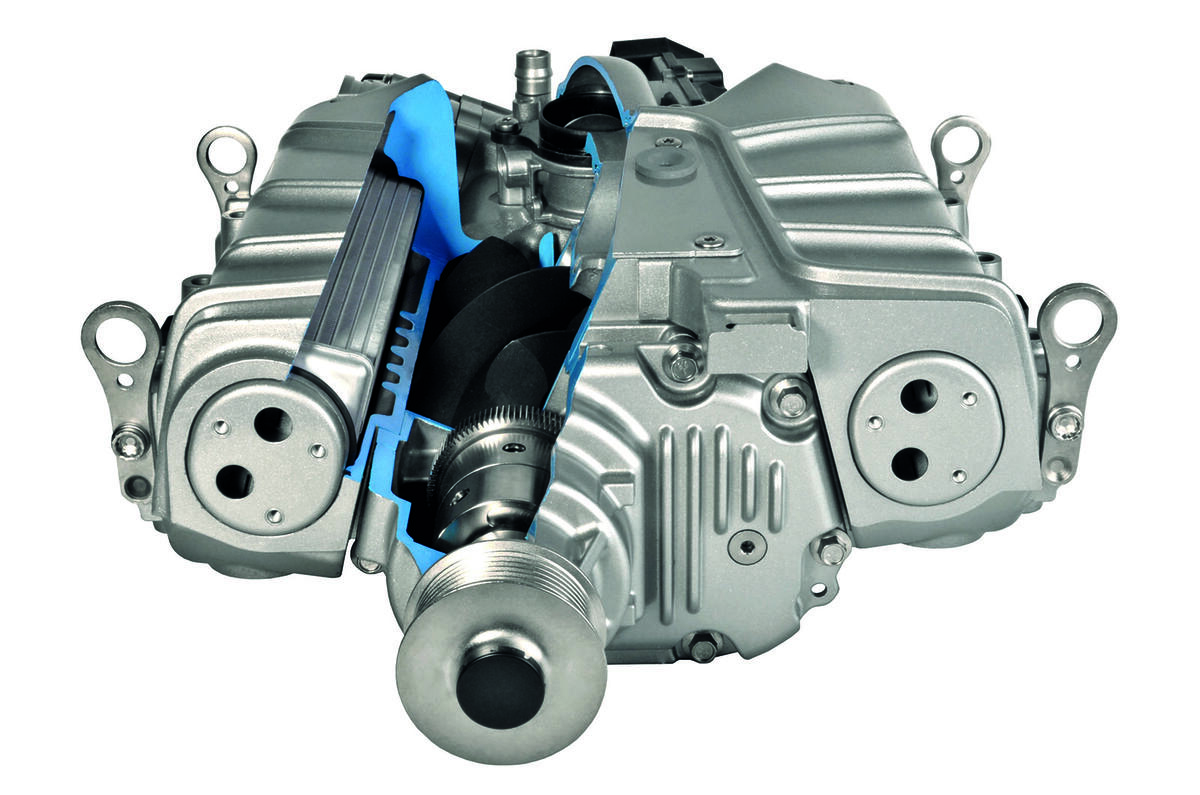

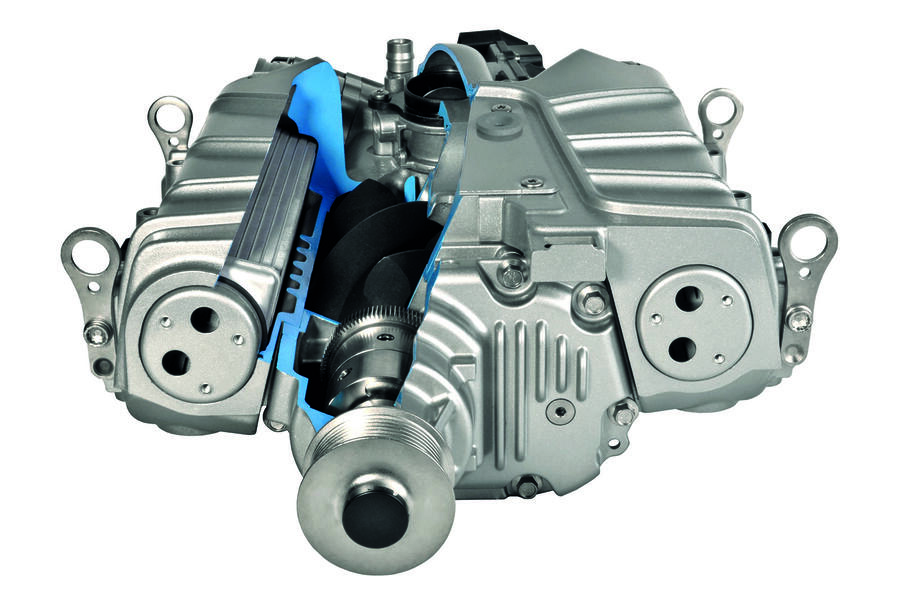

E-boosters replace the turbine with a 48V electric motor, so there’s no exhaust gas involved. The advantage of an e-booster is that it can generate boost when exhaust-gas energy is very low, killing lag to give a snappy response to the accelerator.

E-turbochargers retain the turbine and compressor but add a motor to boost turbo response by overcoming the inertia in the turbine and compressor that makes them reluctant to speed up. It also aids response when exhaust-gas energy is lower and recovers energy via the turbo equivalent of regenerative braking. When the driver lifts, there’s still plenty of energy in the rotating parts and, initially, in the exhaust gas.

In fact, there’s enough that the turbo keeps generating boost when it’s no longer needed. For that reason, all turbo systems have a wastegate valve, to switch the exhaust flow away from the turbo and directly into the exhaust manifold, and a dump valve, to release boost pressure from the engine intake side. An e-turbocharger harnesses that excess energy to generate electricity, which is stored in the battery of a hybrid.

The Mercedes-AMG Garrett E-Turbo incorporates a motor just 40mm thick, sandwiched between the turbo’s turbine and compressor housings. The motor spins up the turbo compressor prior to the exhaust gas energising the turbine so that, even at idle, response is instantaneous, reducing “time to torque”. The beauty is that one turbo can do the job of both a small, fast-reacting turbo and a larger turbo usually needed to pump enough air at high power.

It means the turbo can, as Garrett puts it, be “right-sized” for the job – something that will be essential for combustion strategies to meet future emissions regulations.

Join the debate

Add your comment

Yeah, but

as soon as any efficiency saving are made, what do the motoring industry do with the efficiency savings? Answer: they start building ridiculous and inefficient vehicles to ensure that you get the same MPG that you started out with.

Turbo

Ans, because with turbos performance levels have moved up another step. Take the Puma recently reviewed, 1.0 hybrid with Turbo knocking out 150 with plenty of torque.

Take the Turbo away and the thing will hardly move. Take the hybrid system away and you'll barely notice even with a full charge, then there's the weight, added complexity of the hybrid system and high price.

Why do you need the turbo

The effect of the ima on my Honda's was certainly similar to a low pressure turbo on a downsized engine like fords 1.0 3 pot turbo, so surely if a larger motor was applied a larger more powerful boost could be achieved?