It's human nature to ask: ‘Which is better?’ Even if the answer is usually ‘neither’, because each has its pros and cons.

People will still question whether it’s iPhone or Android, PlayStation or Xbox, manual or dual-clutch automatic. The same is true of engines, and maybe next it’ll be EV electric drives: radial flux or axial flux?

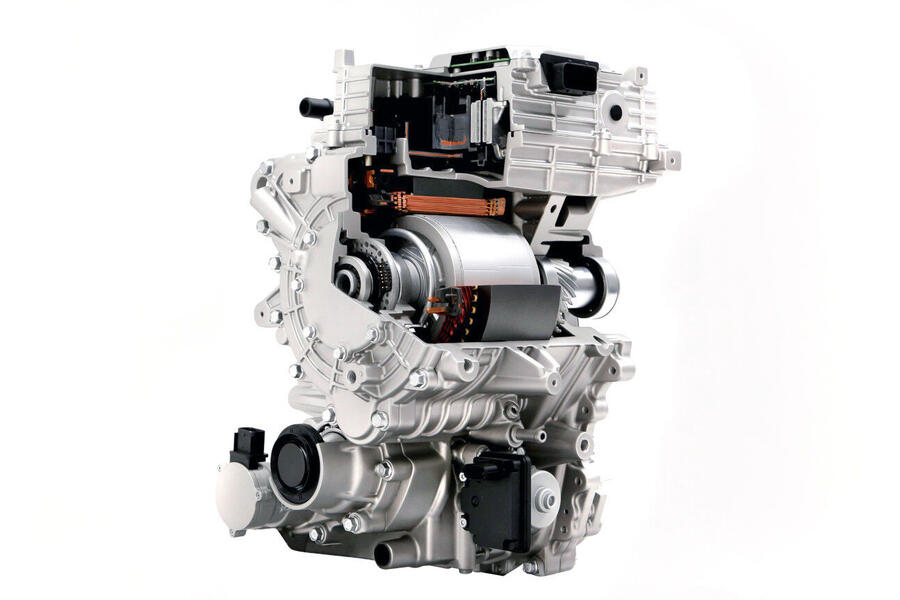

Like the other stuff, each has its pluses and minuses – only in this case, the differences are probably more clear cut. The radial flux motor is the familiar cylindrical shape and the axial flux is shaped like a biscuit tin, and on shape alone they lend themselves to different installations.

The traditional radial flux is a natural fit between two wheels on a single axle because it’s greater in length but smaller in diameter. Axial flux is greater in diameter and extremely short in length so it’s perfect for sandwiching between an engine and gearbox for hybrid drives. There’s not much future for that idea in the UK any more, but in EVs axial flux motors can also work in pairs mounted close to the wheels as drive units, or as wheel motors, or stacked one behind the other to make multi-rotor units.

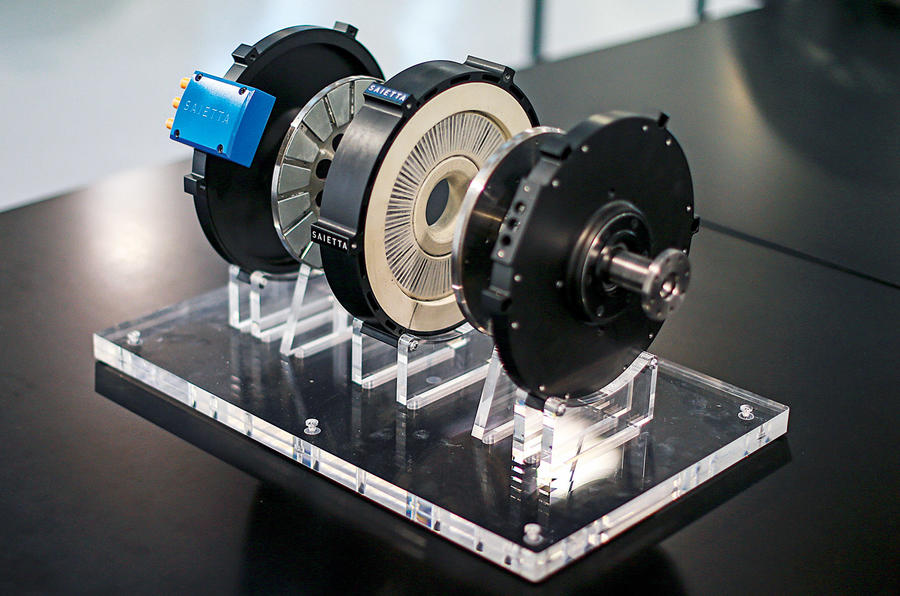

Like radial flux motors, they can be designed to work at low voltage (48V) for scooters and small city EVs or, in the future, autonomous pods, as well as at high voltage for any kind of EV up to supercars. UK-based firm Saietta has designed a new axial flux traction (AFT) motor to suit mass production and bring costs down. It can be scaled in size to power anything from a scooter to a bus.

The use of simple mild steel in the disc-like rotor with permanent magnets attached helps reduce cost, as does the modular construction, which lends itself to a high level of automated assembly – the secret to producing large numbers and reducing cost. The motor is sealed and water cooled and, like other axial flux motor designs, is ‘yokeless’, missing the bulky, heavy frame supporting the stator windings of a traditional radial flux machine. The lack of yoke is one of the features that reduces weight and increases power density.

Like all types of AC synchronous electric motor, the magnets on the rotor of an axial flux motor are attracted to the rotating field created by a surrounding ring of separate electromagnets in the stator. The switching of the magnets making the field rotate isn’t dead smooth and so the rotor suffers from a slight ‘torque ripple’ known as ‘cogging’ as it turns.

Although the effect is usually reduced electronically, Saietta motors have 96 electromagnets in the stator, the high number and smaller increments helping reduce it to a minimum. Saietta was recently the recipient of an Advanced Propulsion Centre grant to help establish production processes to manufacture 150,000 motors a year and sees potential in producing wheel motors for autonomous pods as well as conventional vehicles. It will join other axial flux motor developers such as established YASA and Belgium firm Magnax in moving electric motor technology forward.

Add your comment