Slide of

Slide of

Like many automakers, Studebaker started out by not making cars at all.

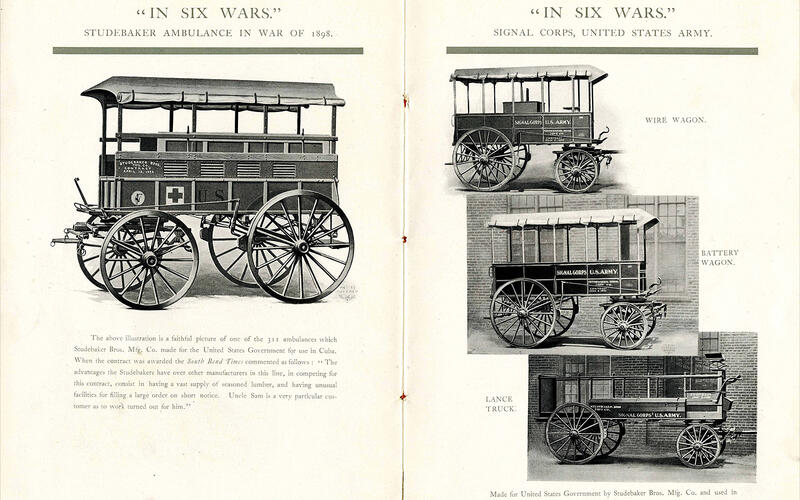

Founded in 1852, the business began life as a maker of wooden horse-drawn wagons. At which it became very successful – the world leader, in fact. It read the market well, too, experimenting with cars at the dawn of the 20th Century, and by 1902 was building small numbers of automobiles alongside its wagons, most of them electric. By 1911, Studebaker was the second best-selling car brand in the US.

Although it would never again hold that position, plenty more success was to come, and with it several legendary cars. Growth continued, but it was one of many automakers that found it hard to compete with the Big Three. This is the story of a remarkable company that knitted itself into America’s firmament, only to succumb to the vagaries of the marketplace:

Slide of

Slide of

Beginnings

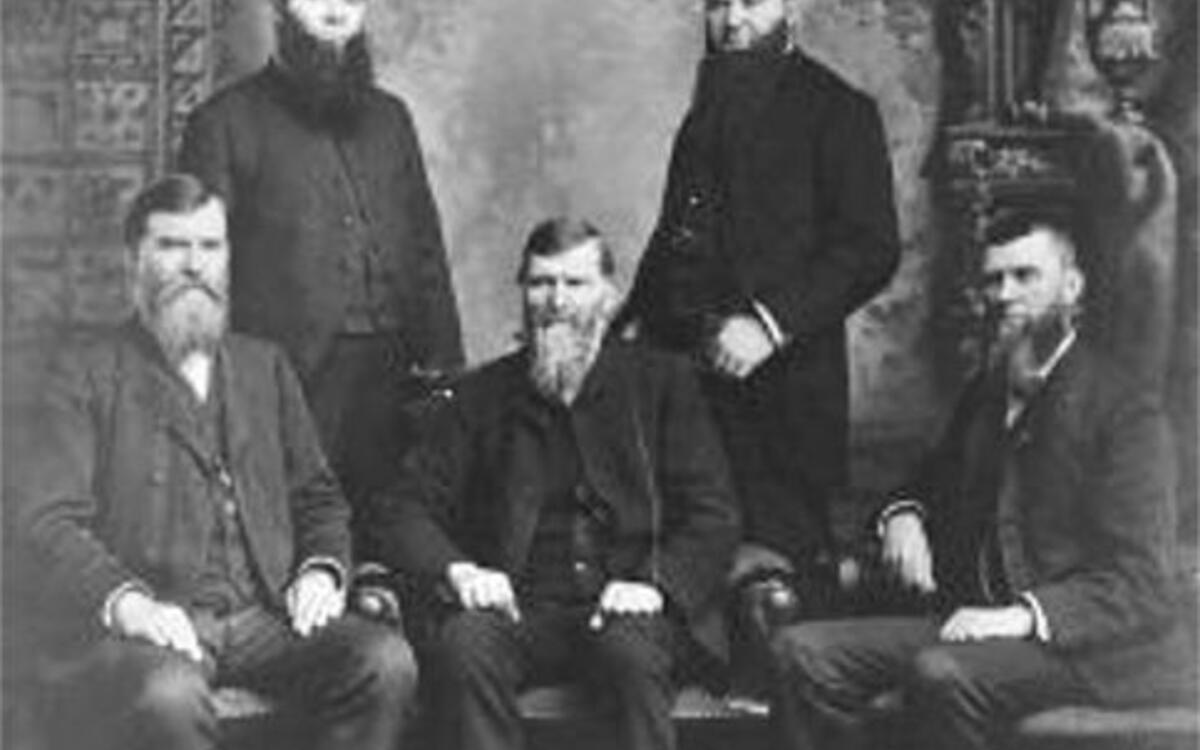

The Studebaker brothers were grandsons of German immigrants. Clem and Henry (pictured seated at left and center respectively), the eldest of the five - there were five daughters, too - left their Ohio family home in 1850 for South Bend, Indiana, founding H. & C. Studebaker in 1852.

Slide of

Slide of

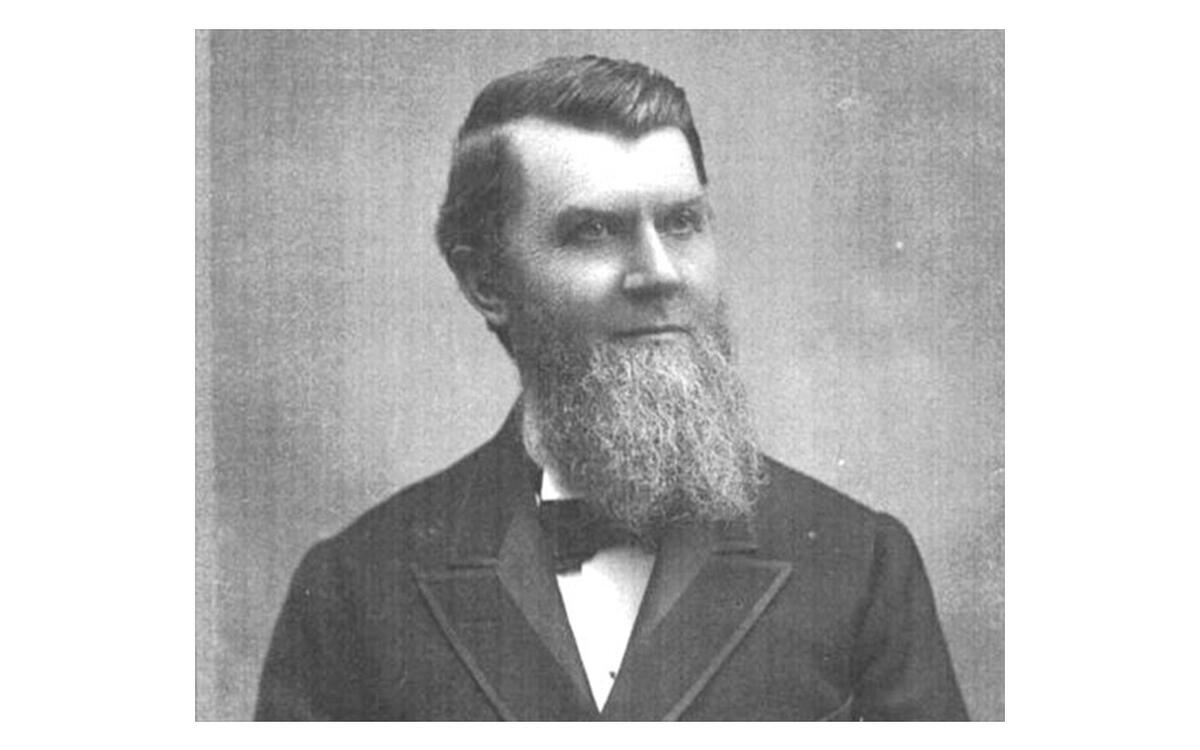

John Mohler Studebaker

It was a small-town business in a small town, the workforce of two seeing a 50% increase with the arrival of an enterprising third brother, John Mohler (pictured). But at the last minute the Californian gold-rush tempted him instead.

He paid for his passage with a wagon constructed by the three of them. When he arrived he was persuaded to join a firm making wheelbarrows for miners. Less exciting, but more lucrative than the gold-grubbing efforts of his friends, which yielded little.

Slide of

Slide of

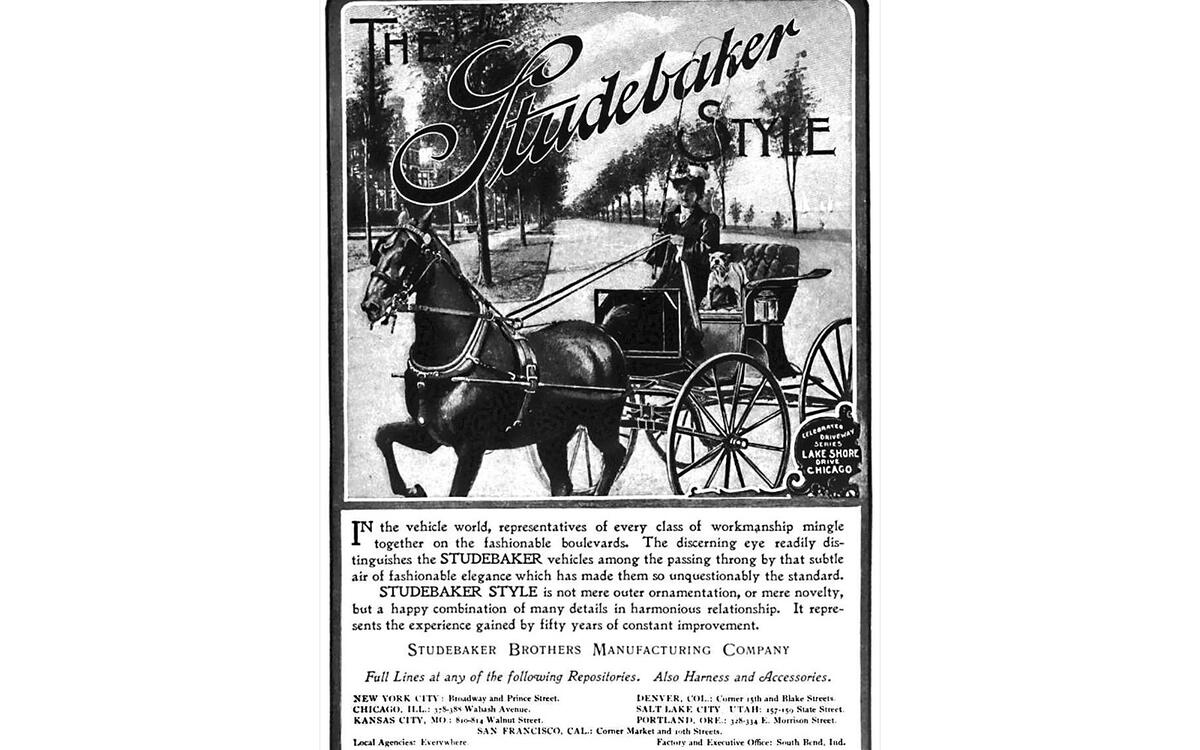

Carriage champ

Having made a small Californian fortune, John Mohler moved to South Bend in 1858 and bought Henry out. A decade later Studebaker was the largest vehicle builder in the world, making a wagon or carriage every seven minutes. They maintained their lead to the turn of the century, with annual sales revenues of over $2 million, equivalent to around $70 million in today’s money. By then Studebaker brothers Peter and Jacob had also joined.

Slide of

Slide of

Enter Edison

As the age of the automobile dawned Studebaker experimented with electric carriages in 1897, supplying bodies for electric cars shortly after. A series of 20 electric cars, designed by one Thomas Edison (on the left here) of light bulb brilliance, followed in 1902.

Slide of

Slide of

Gasoline arrives

Clem Studebaker, co-founder of the original company with brother Henry, had died the previous year in 1901. Henry, a pacifist, had left the company many decades earlier when it began supplying wagons to the Union Army in 1861, leaving John Mohler as president. He realized that the ‘horseless carriage’ was a development that could not be ignored, though he thought motor cars would be too expensive to buy and own for the average person. And indeed, he was right – at least for the time being.

By 1904 Studebaker had made the coachwork on its ‘first’ gasoline-powered car, a 16HP twin cylinder touring car named Model C. The chassis and engine came from partner Garford Company.

Slide of

Slide of

New era

In 1911 it bought Detroit’s Everitt-Metzger-Flanders company to form the Studebaker Corporation. The new range included three gasoline models and Studebaker’s electric cars. By 1913 all had been replaced by a range of four- and six-cylinder gas cars; that year it was the third largest US automaker, behind Ford and Willys-Overland.

The cars were still made in Detroit, but in 1920 production shifted to South Bend. Wagon production swelled during the First World War and many were supplied to the Allied powers, but production ceased in 1921. It was a far-sighted decision to exit a business that had no future; Studebaker was already making over 100,000 cars a year by this stage – and added trucks, buses and fire engines to its output.

Slide of

Slide of

The models

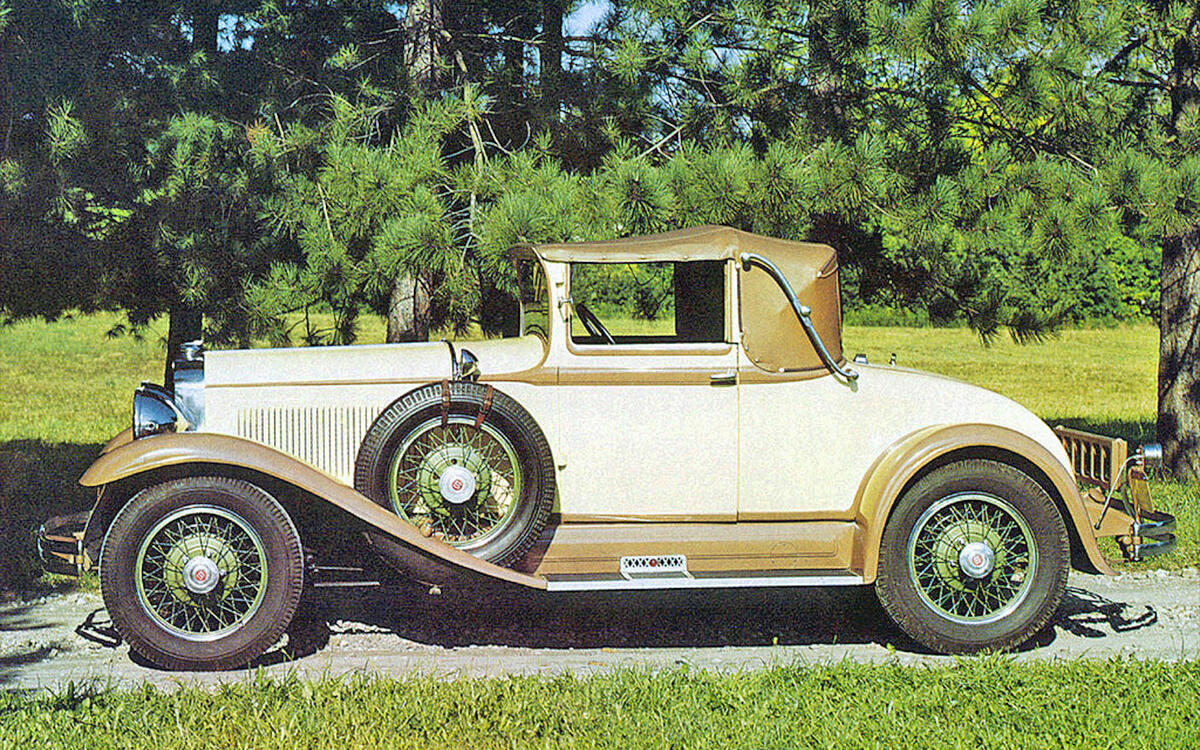

With names like Big Six, Light Six, Special Six and Standard Six, Studebakers’ model names were a bit repetitive in the late 1910s and early ‘20s. But having thought about male buyers and their egos, Studebaker relaunched in 1927 with Commander, President (pictured) and – unwisely – even Dictator model names. This latter name was dropped in 1937, with a nod to the international situation…

Studebaker displayed boldness in other directions too, taking on the struggling luxury auto-maker Pierce-Arrow, based in Buffalo, New York. A year earlier, it had built a new engineering facility at South Bend, said to be the world’s best.

Slide of

Slide of

Erskine

Also new for the 1927 model year was a smaller, high quality model of mildly European style and taste rather unappealingly named Erskine, after Studebaker’s boss – an example of Studebaker attempting the multi-brand approach of fast-growing Detroit-based rival General Motors.

The company dubbed it “The Little Aristocrat”, but only 80,000 were sold over the next four years despite increasingly extensive reworkings of its look. By 1930 the name was abandoned, the car rebadged Studebaker.

Slide of

Slide of

Straight Eight

More successful was the range-topping 1927 President Eight, initially a six-cylinder, but from 1928 powered by a supercharged straight-eight generating 100bhp. Keenly priced for its type and the winner of many speed records - 30,000 miles in 27,000 minutes among the more curious – the President turned Studebaker into the world’s biggest seller of straight-eights.

Slide of

Slide of

Giant

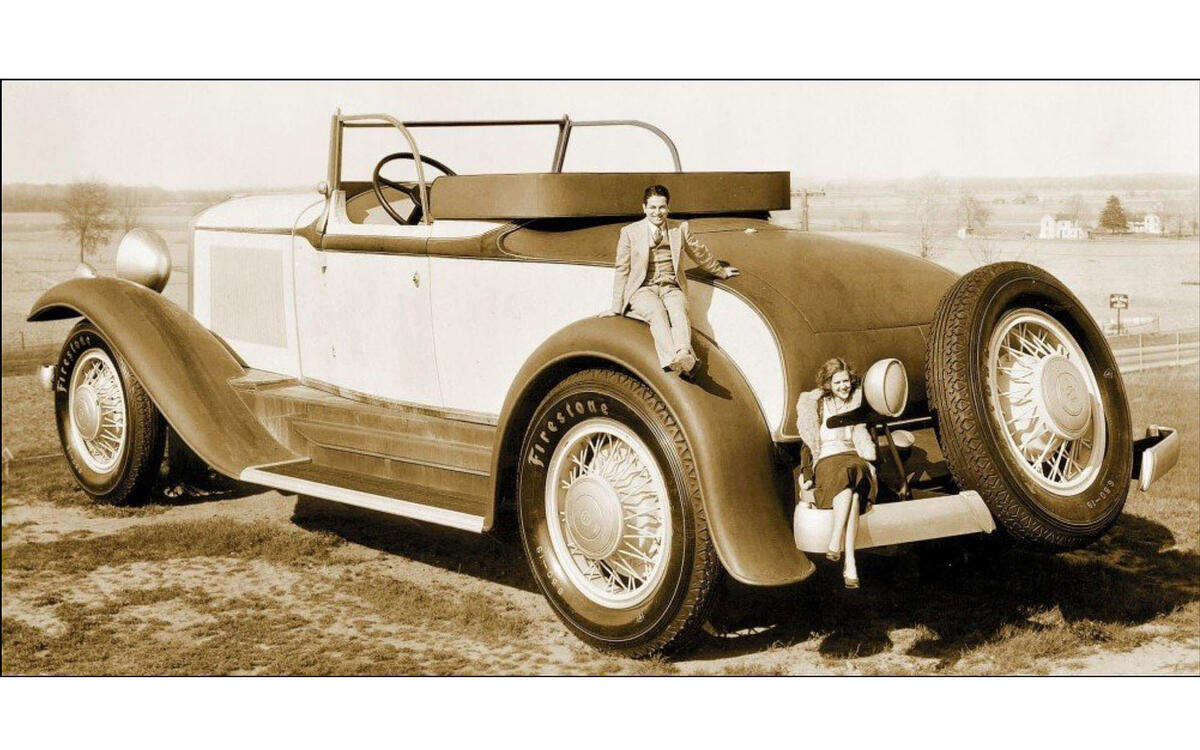

The President range evolved to a peak for the 1931 model year, these cars considered the finest Studebakers ever produced. To promote them, Studebaker built “the largest car in the world”, a wood and plaster cast model 41 feet long, 15 feet wide and 13.5 feet tall. It weighed 5.5 tons.

The roadster featured in a nine-minute film played in RKO theatres across America, where it was used as a prop by entertainers called the “Studebaker Champions”. Sadly by 1936 company bosses decreed that the giant car had outlived its usefulness, and burned it to the ground.

Slide of

Slide of

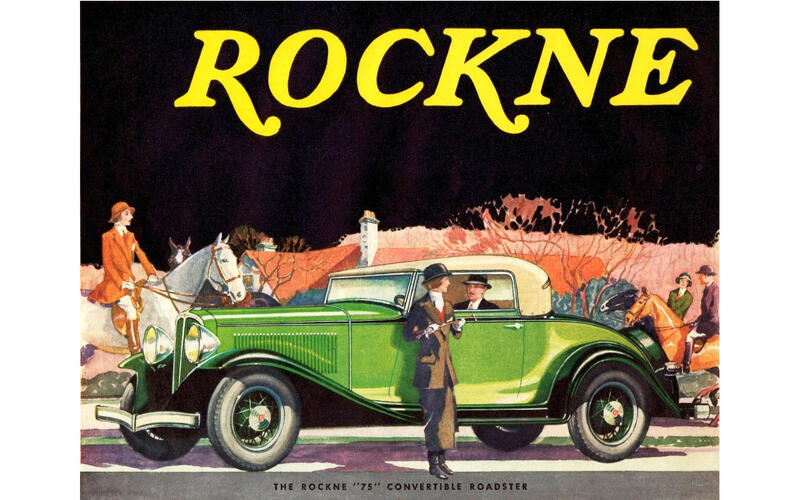

Rockne

A hefty straight-eight was not the right car for the Great Depression that followed the 1929 Wall Street crash, Studebaker having another attempt at a small car in 1931 with the Rockne. It was named in honor of admired football coach Knute Rockne, who worked at University of Notre Dame, located just outside South Bend. Rockne had recently been killed in a plane crash.

The Rockne ought to have been what the market needed but despite a decent design and keen pricing the model found only 23,000 buyers over two years.

Slide of

Slide of

Depression

And Studebaker would succumb to the Great Depression. Profits dropped alarmingly in 1930, from $11 million the previous year to $1 million. Big dividends to shareholders continued to be paid though, and the firm fell into loss in 1932.

Were it not for the recession Studebaker would have been highly competitive, its range spanning from the Rockne to the Studebaker Six and Eight, and above those the Pierce-Arrow range, the latter of which were some of the grandest cars America has ever made. There were also truck ranges from both brands.

PICTURE: Famed racecar driver Phil Hill at the wheel of his 1931 Le Baron Pierce-Arrow, which he bought in 1955

Slide of

Slide of

Rescue

The big dividend payments together with declining sales crippled the firm, and after an attempted merger with a truck company, it went into receivership and its boss Albert Erskine committed suicide.

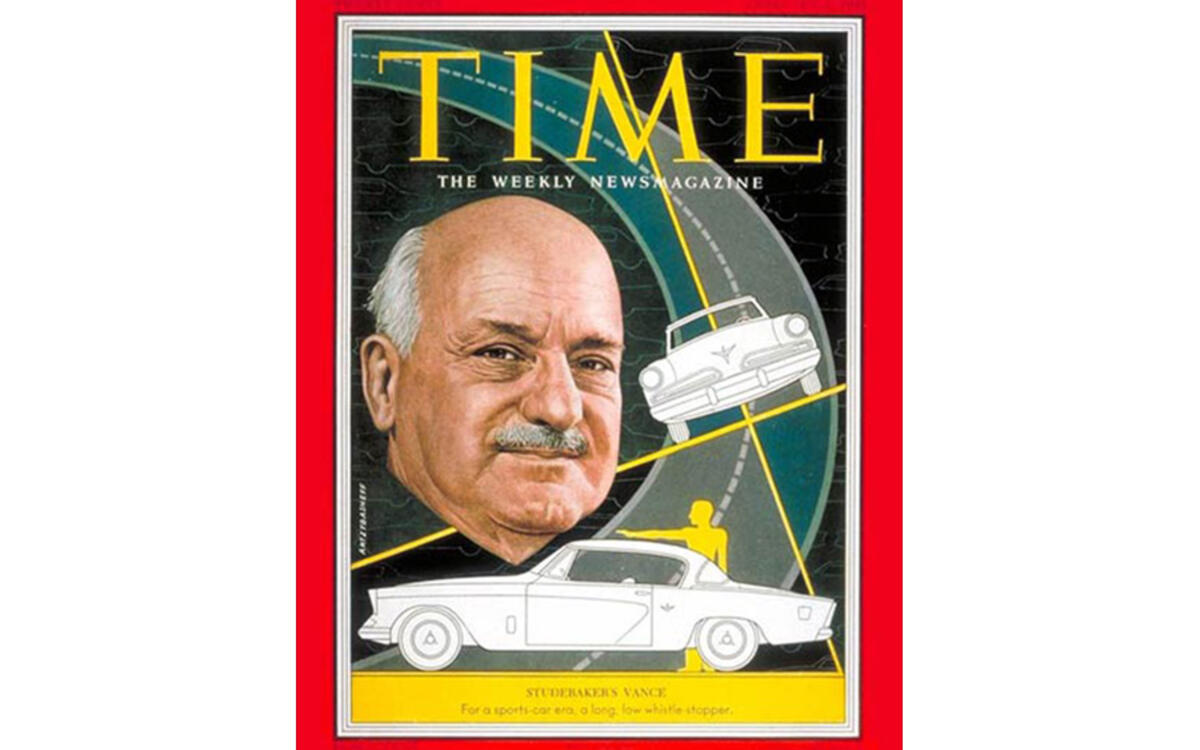

Sales boss Harold Vance and chief engineer Paul Hoffman were determined that Studebaker should recover. They raised $1 million by selling Pierce-Arrow, negotiated credit with the banks, cut prices and turned a modest profit within months. By March 1935 the company had escaped the receivers. Vance would go onto become one of America’s most celebrated auto chieftains, earning himself a Time magazine front cover in 1953 (pictured).

Slide of

Slide of

Champion

The new management looked once more at the smaller car market. Market research revealed that nearly 90% of car owners earned less than $60 a week, were unhappy with the cost of buying and owning a car – but didn’t want a small, uncomfortable or under-powered one either.

Studebaker’s previous small cars used many components from its larger models, which were often over-weight and over-engineered. The proverbial clean-sheet design was the answer, the resulting 1939 Champion hundreds of pounds lighter than its Ford, Chevrolet and Plymouth rivals, improving on their economy by 20%.

Slide of

Slide of

Champion curtailed

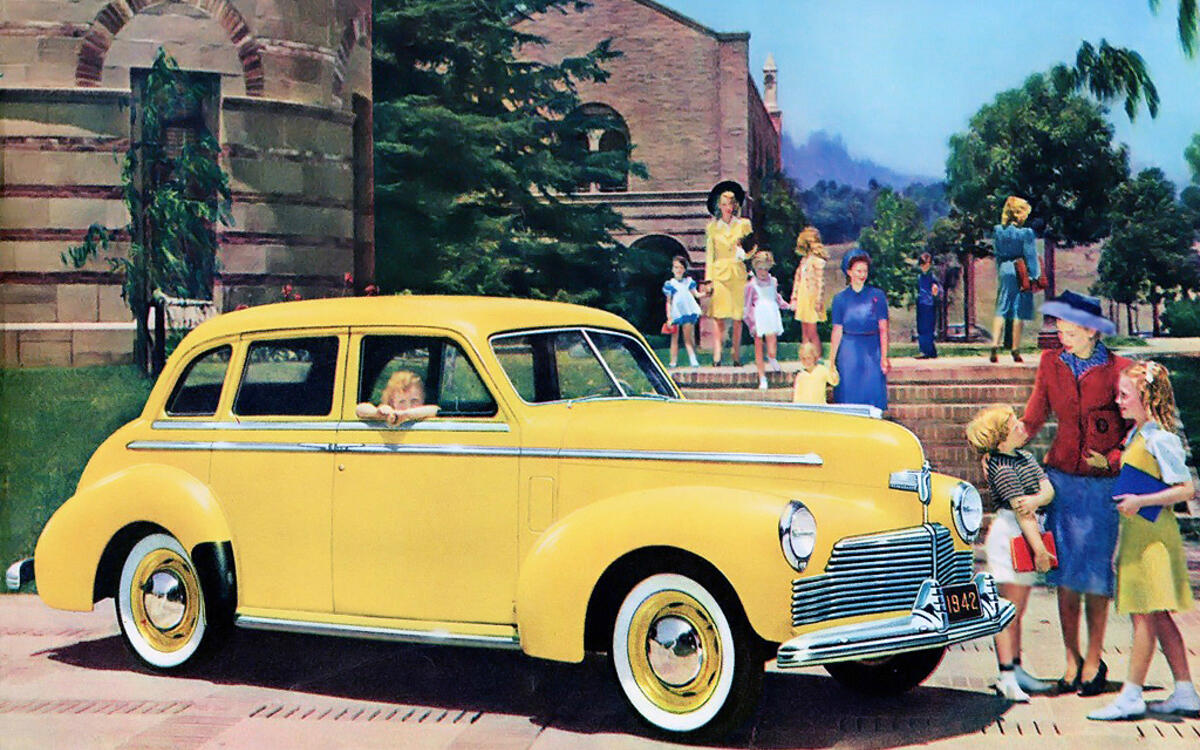

The fleet-footed Champion was an immediate hit, and not only because it was economical. It rode well, had decent looks and performance and was far from a stripped out poverty model. Studebaker’s sales grew 87% in 1939, the Champion accounting for almost 60% of its sales and returning the company to profit.

But in its three years on sale the Champion scored over 215,000 sales and pushed the company’s turnover past $100 million, and it got a mild refresh for the 1942 model year (pictured), at which point a world-changing event on the Pacific island of Oahu curtailed production.

Slide of

Slide of

Studebaker goes to war

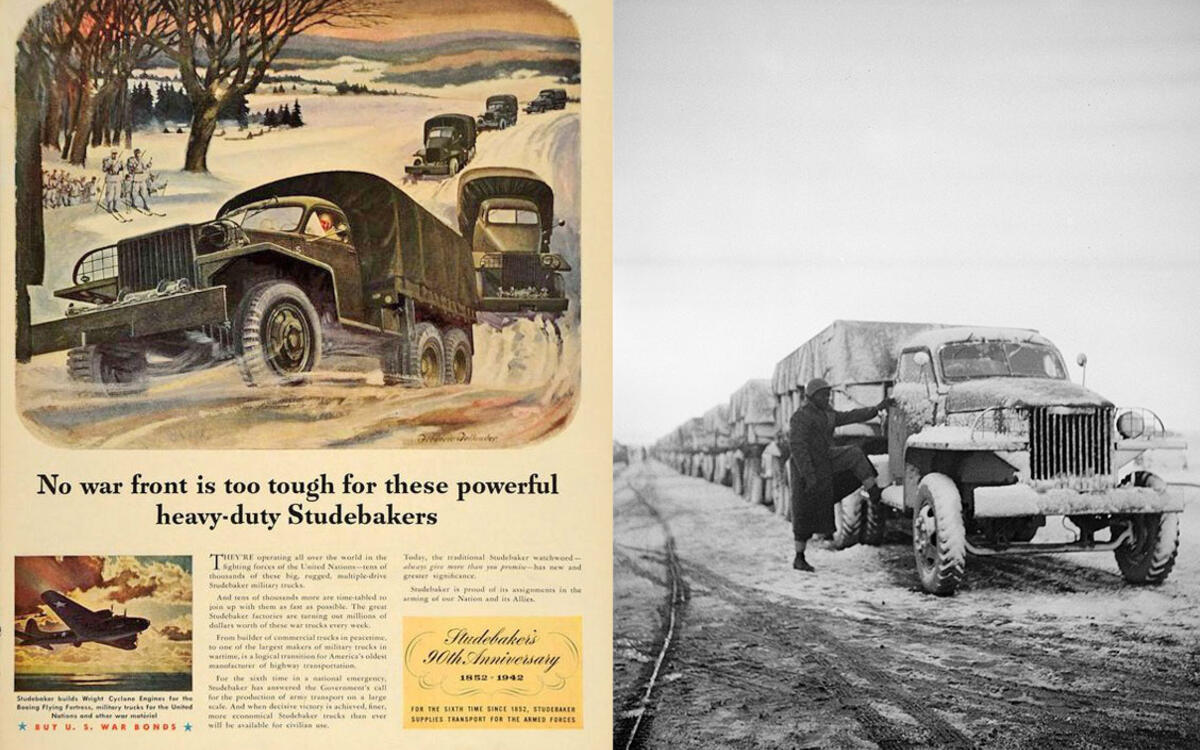

With the entry of the United States into the Second World War after Japan’s attack on the US Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbor, civilian car production was ended and the production lines of Studebaker and the rest of the vast US auto industry got turned over to making war materiel of various shapes and sizes – as the more far-sighted senior members of Axis regimes long-feared they would be.

Studebaker license-built 63,789 Wright Cyclone airplane engines for Boeing’s B-17 Flying Fortress bomber that served mainly in the European theatre, and it also made the M-29 Weasel tracked vehicle, which did good service during amphibious landings such as those at Iwo Jima. As you can see from these period advertisements, the company was proud to underline its contribution – and perhaps mindful of the day when the company could sell cars once more.

Slide of

Slide of

US6

But perhaps Studebaker’s biggest impact was the development and production of the US6 heavy truck. Around 197,000 were produced by the company and as many as half of them were sent to Russia under the Lend-Lease arrangement where they helped to transport the troops and weapons that turned the tide against the German invaders. They were all either four-wheel- or six-wheel-drive, a factor that proved critical in a part of the world where proper roads were thin on the ground.

The model became well known for its ruggedness and reliability, and respected for its ability to run on poor-quality fuel – as little as 68-octane. The Soviet leader Joseph Stalin sent a personal letter of thanks to the company for the US6. The trucks were powered by a 5.2-liter straight-six gas engine delivering 86 hp and 200 LB-FT of torque – meagre by modern standards for sure – but strong numbers for the time and more than direct German rivals from Opel and Mercedes-Benz, many of which were driven by the rear-wheels only.

Slide of

Slide of

Peace

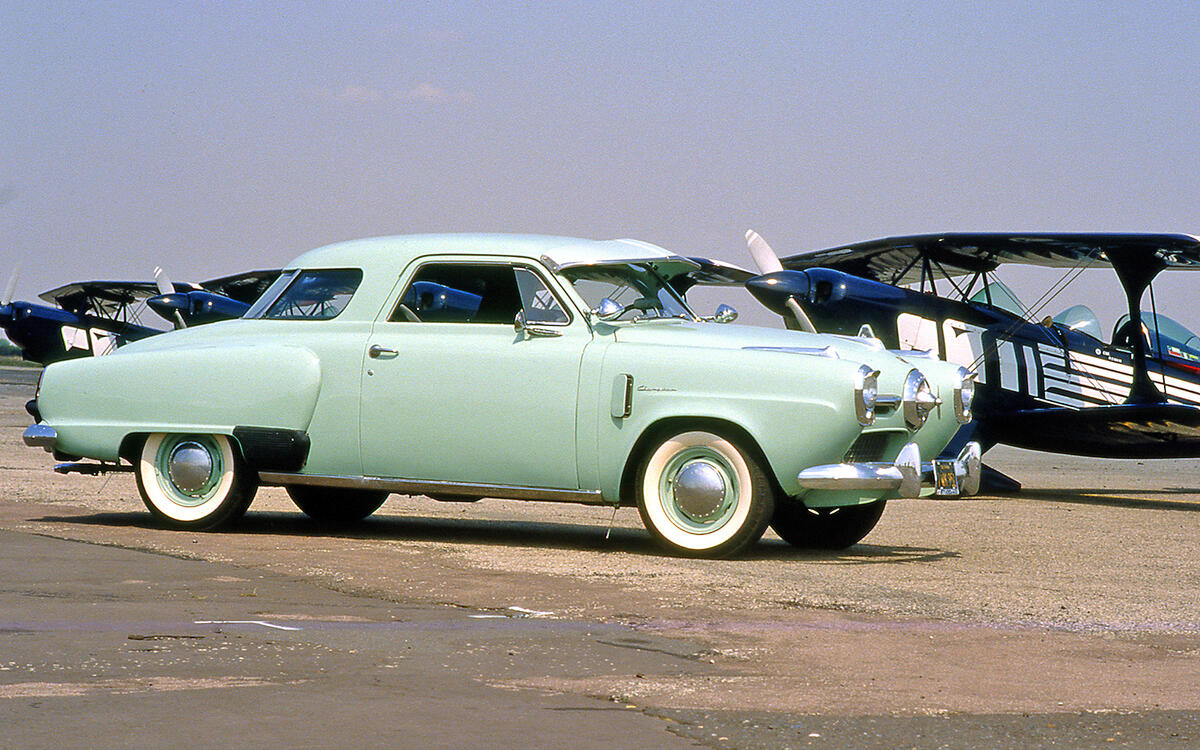

Any immediate post-war launch of an all-new model wasn’t possible for Studebaker or any other US automaker since it took time to rejig production lines for peacetime use, and deliver new designs. Studebaker’s aim, however, was to be the first US maker to sell an all-new, post-war style.

And jeepers, was it new. The legendary Raymond Loewy industrial design studio was engaged to produce some visual drama, and together with in-house design chief Virgil Exner duly delivered with a car whose rear end almost mirrored its front. This was especially true of the coupe (pictured), whose four-piece wraparound glazing resembled a windshield. The public called them “Coming-and-Going” cars. No less arresting, although it seems ordinary today, were fenders near-flush with the car’s flanks.

Slide of

Slide of

Changes

Studebaker’s design department didn’t stop there, the 1950-51 version receiving a bullet-nosed grille (pictured). That made it slightly easier to tell whether the Champion was coming or going, besides adding extra visual drama. Mechanical modernity appeared with the latest Commander sedan, its optional overhead valve V8 only beaten to market by Oldsmobile and Cadillac.

The Champion, Commander and Land Cruiser sold 268,000 units in 1950, winning the company a 4.1% US market share. By 1952, Studebaker was celebrating 100 years in business. That coming of age would be marked with launch of a model even more striking than the coming-or-going Champion.

Slide of

Slide of

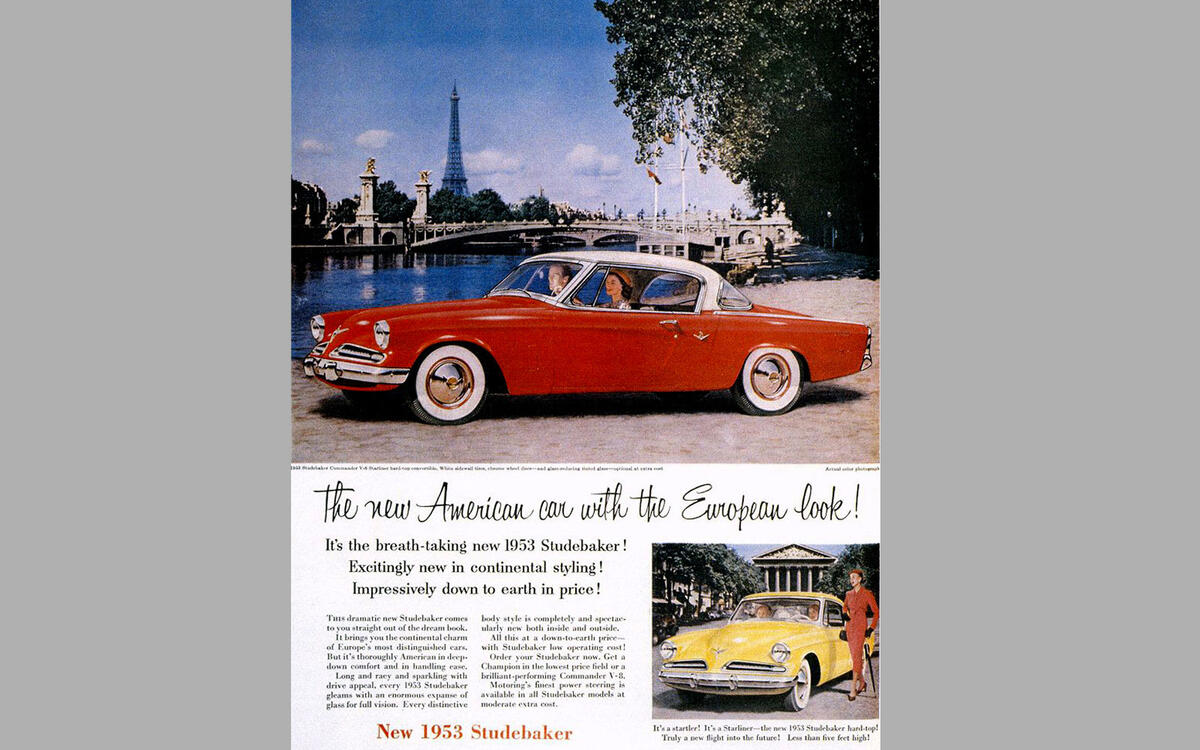

Starliner

The 1953 Studebaker Starliner was that car. It was designed by the Raymond Loewy Studio, as all Studebakers had been since 1938, and specifically by Robert E. Bourke. There was also a very similar new Starlight coupe, this version fitted with “B” pillars, whereas the more hardtop Starliner was shorn of these for an elegantly pillarless look.

The Starliner often appears in lists of the world’s most beautiful cars. “I patterned it after the Lockheed Constellation airplane,” said Bourke. “The nose-down feel of the fuselage in particular was reflected in the front fender and hood contours. For side definition I used a sweeping ‘character line’ running from the front fenders through the door, then down in a reverse angle matching that of the rear fenders.”

Slide of

Slide of

Merger

The design received much acclaim, including from the Museum of Modern Art, but this slender, clean-cut, four-seat coupe, though successful in its own right, could not do enough to revive Studebaker’s now sagging sales. From that 1950 peak the company’s share fell to 3% and 160,000 sales in 1952, the Starlight and Starliner able only to push this to 186,000 units the following year.

Studebaker was increasingly feeling the heat from both Detroit’s Big Three and a decline in military contracts, along with the self-inflicted poor quality of Starlights and Starliners which damaged sales. In 1954 Studebaker was bought by Packard, the pair attempting to bulk up for survival.

Slide of

Slide of

Golden Hawk

That union did little to help Studebaker and still less for Packard, which suffered the indignity of selling one badge-engineered Studebaker in 1957 before disappearing a year later. The Starliner was successfully facelifted into the Hawk series of coupes, and if its nose appeared more brash with its enlarged grille, the four-strong model range rejuvenated sales for a while.

The most exciting model in the range was the Golden Hawk (pictured), whose 352 cu in (5.8-liter) Packard engine provided dramatic performance, with rather nose-heavy handling. In 1957 the Packard engine was replaced by a still heftier supercharged Studebaker V8. In either form it was a quick car, outsprinting Big Three rivals in the shape of the Chrysler 300B, Ford Thunderbird and Chevy Corvette.

Slide of

Slide of

Scotsman

Famous name that Studebaker may have been, but it continued to lose sales and haemorrhage money, endless reworks and realignments of its existing models doing little to stall the decline. An exception was 1957’s Studebaker Scotsman, a stripped out, budget model that was the cheapest car on sale in the US. FDR’s widow Eleanor Roosevelt was among its buyers.

Slide of

Slide of

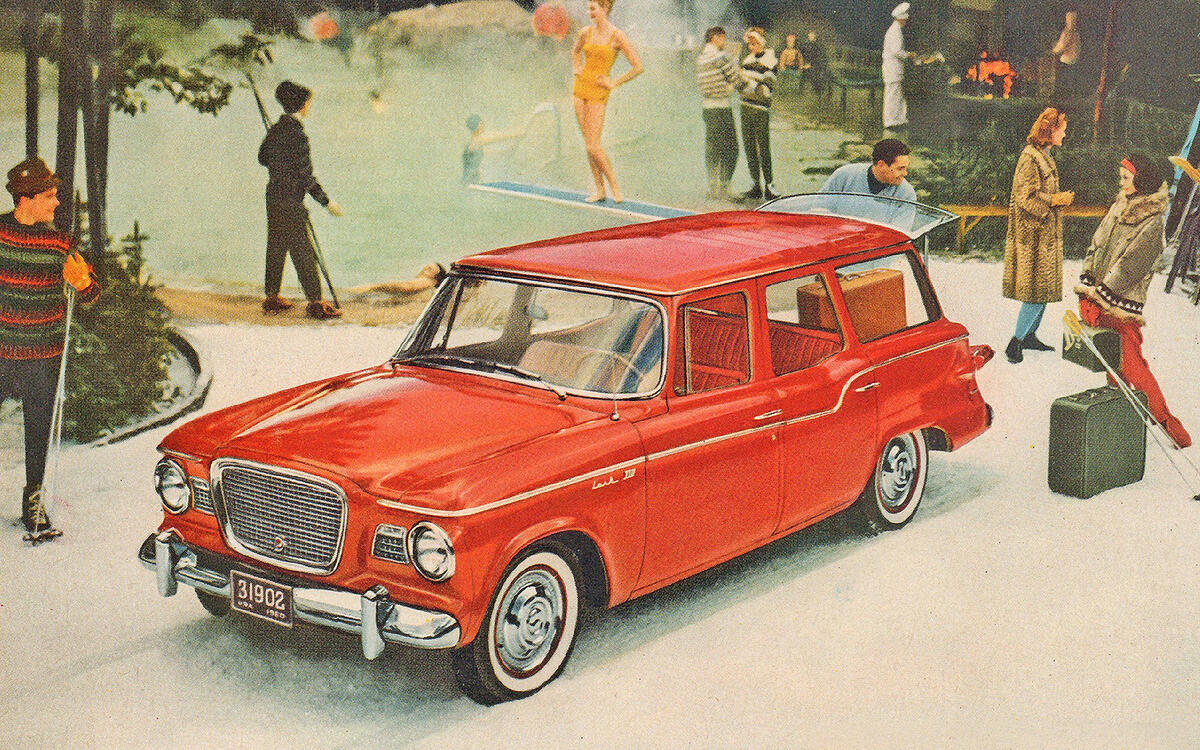

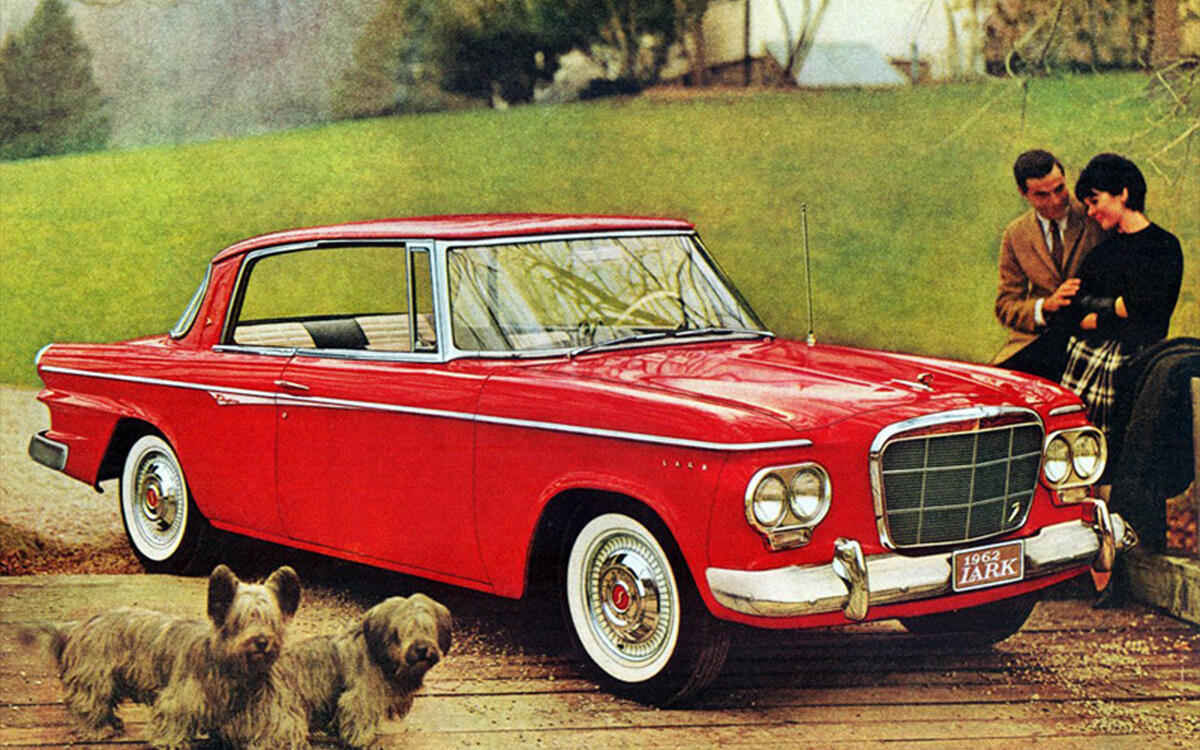

Lark

The Scotman’s modest success encouraged boss Harold Churchill to pursue a new, smaller budget model, the recession forecast for 1958 a further spur. Although it looked all-new, the resulting car, the Lark, was a cleverly redesigned version of Studebaker’s 1953 Champion. It was 27 inches shorter but the center section of the old car was retained, enabling the Lark’s cabin to seat six.

Less bulk meant less weight and lower build costs, but the Lark cost usefully more than the old Scotsman, enabling Studebaker to finally return to profit. Attractive styling and decent assembly quality also helped. Studebaker sales leapt from 79,000 in 1958 to 182,000 the following year.

Slide of

Slide of

Redesign

With this success Churchill reckoned the Lark could combat the new compact models coming from the Big Three by merely evolving the Lark, in much the same way as VW was with its fast-rising Beetle. But the new Chevrolet Corvair, Ford Falcon and Plymouth Valiant stole big chunks of business from Studebaker, sales once again plunging.

By late 1959 Churchill realised that the Lark would need updating, and initiated two new compact models, the smaller of them to use a water-cooled flat-four.

Slide of

Slide of

Expansion

The Studebaker board had other ideas, recently recruited director Malcolm Sonnabend keen to use Studebaker’s string of tax loss credits to expand and diversify. Profitable companies making plastic rocket nose cones, tractors, generators and floor-cleaning equipment were bought, keeping the company in the black for 1960 and the factories at South Bend (pictured) busy.

But Studebaker’s new president Clarence Francis scrapped Churchill’s economy car programme, the man himself then kicked upstairs to a consultancy role.

Slide of

Slide of

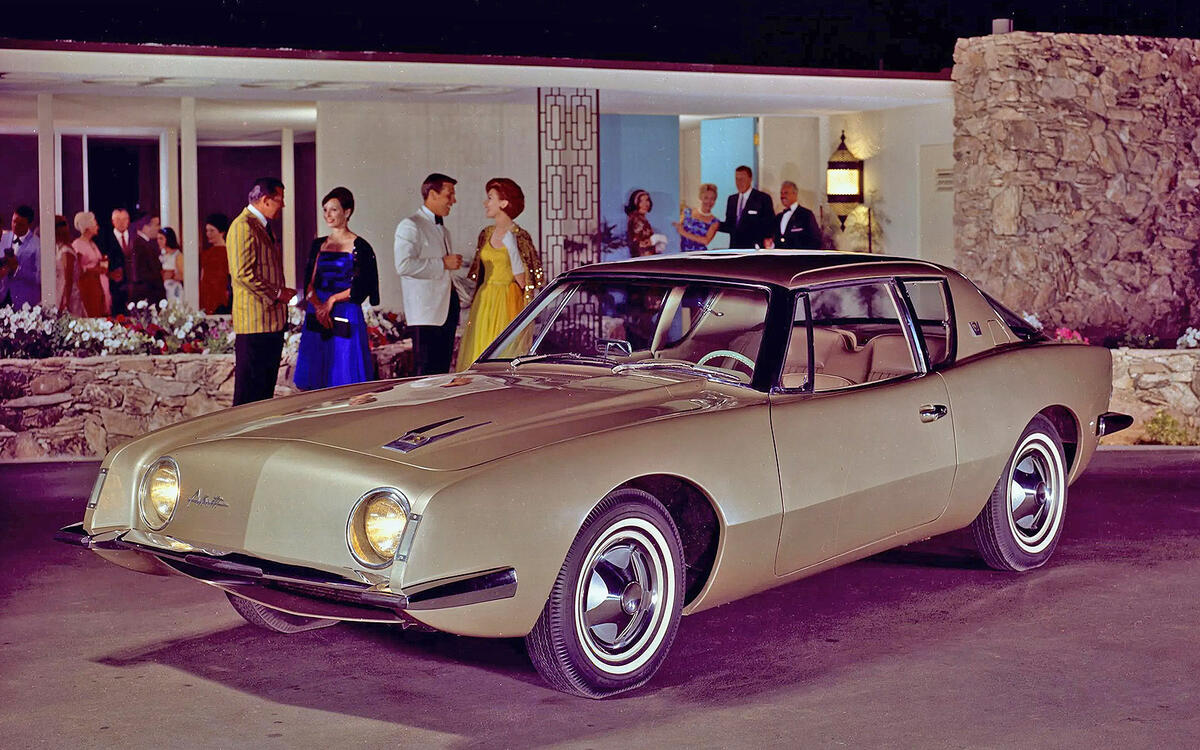

Enter Avanti

The Lark remained in production, but Francis attempted to keep Studebaker in the car game by commissioning a striking redesign of the Hawk coupe from Brooks Stevens for 1962, and the upmarket, Loewy-designed, plastic-bodied V8 Avanti coupe a year later.

The supercharged R3 version of the V8 Avanti was good for 170mph, making it the fastest car ever sold in America, as well as being the first US model to have disc brakes and a built-in rollover bar.

Slide of

Slide of

Invention

The Lark was continuously evolved and updated, if not as fundamentally as Churchill had planned, the efforts of designer Stevens and yet another new president, Sherwood Egbert, achieving a 50% sales increase for 1962. The Lark name was gradually usurped by the Cruiser and Daytona, but the roots of these cars remained the same.

More inventive was the Lark Daytona Wagonaire (pictured), a wagon whose rear roof section slid forward to reveal an open-topped load bay. The rear window retracted into the drop-down tailgate, producing a versatile design that decades later, would part-inspire the 2004 Opel Trixx concept.

Slide of

Slide of

Future

The image benefits of the high performance Hawk Gran Turismo (pictured) and the Avanti nevertheless helped, as did the arrival of motor racing honcho Andy Granatelli, who headed up the Paxton supercharger company that the Studebaker Corporation now owned. By 1963, V8 engines from the Avanti coupe were being offered with the Lark and Lark Cruiser models.

But there was no escaping the fact that annual refreshes, renamings and upgrades were no substitute for the all-new mainstream model needed if Studebaker’s car business was to have any hope of survival. But it was not to be.

Slide of

Slide of

Exit

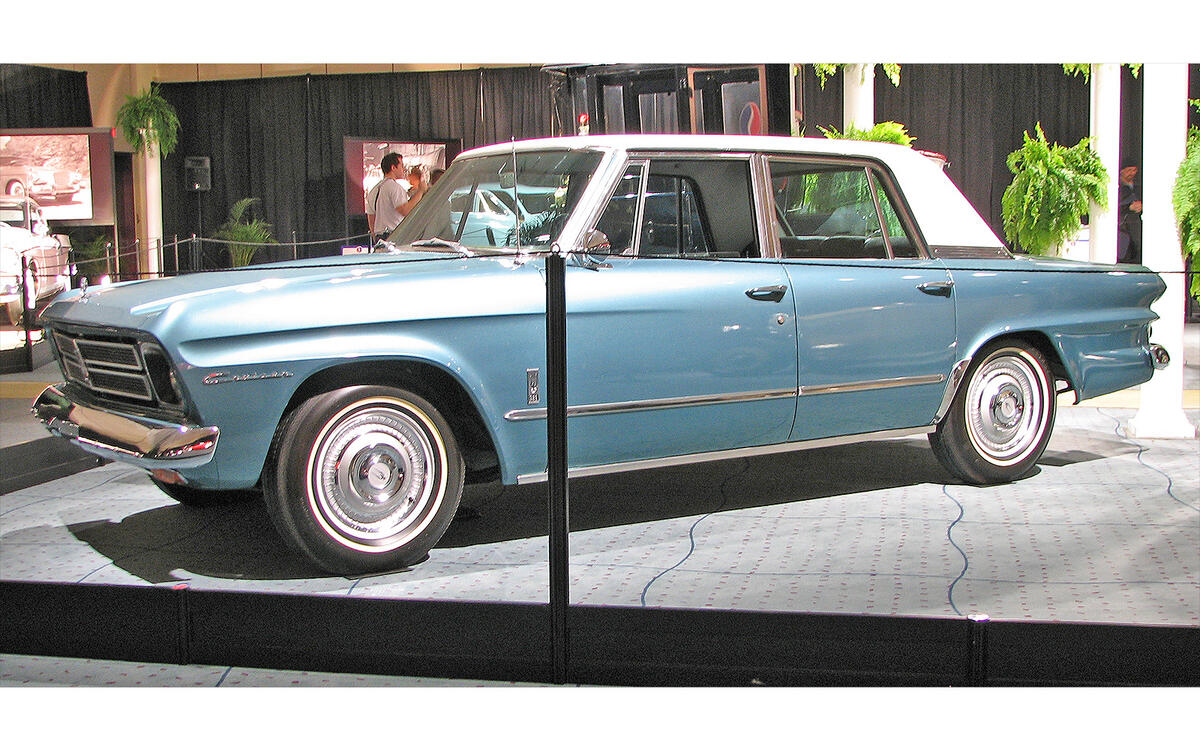

What came next was the withering of the Studebaker auto empire under cost cuts, the famous South Bend factory shut in December 1963, production remaining only at company’s Canadian plant in Hamilton, Ontario. Despite plant boss Gordon Grundy believing in the future of his factory and the brand, the slow death continued.

The cars were now fitted with GM engines, Studebaker’s own engine plant having closed, and with no in-house design or development facilities Grundy had to ship out work on the ’66 models to an agency. Their updates were effective, but it was fast becoming apparent that the Hamilton plant would probably not reach its 20,000 car annual break-even rate. Studebaker’s stock price was being depressed by the failing auto division.

Slide of

Slide of

The end

On March 4 1966 the decision to end production was made and on March 17th the last Studebaker, a V8 Cruiser in Timberline Turquoise with a white roof, left the Canadian production line. It’s now in the Studebaker museum at South Bend (pictured). The Studebaker Corporation flourished after excising the car division.

More companies were bought, and in 1967 it became the Studebaker-Worthington Corporation before being absorbed by McGraw-Edison, the name now preserved merely as a legal entity. But…

Slide of

Slide of

Avanti rides again

When Studebaker production ended at South Bend in December 1963, the closure took the new Avanti with it. Only 4643 cars had been built. Among the disappointed were Nathan D. Altman and his partner Leo Newman, the pair being Studebaker and Packard dealers in South Bend. They persuaded Studebaker to sell them a building, the fixtures and tooling to restart Avanti production, using bought-in Corvette 327 engines from GM.

By the end of 1965 they had built 20 Avanti IIs with the help of former Studebaker employees. Avanti production continued through to 1985, the rights to the company passing through several hands and factory sites before ending up at Cancun in Mexico, where it was run by Michael Kelly. Kelly had previously owned the company in 1986, and repurchased it in 1999. It went under in 2006 when Kelly was arrested on fraud charges over a Ponzi scheme he was running. It brought the history of Studebaker passenger cars to a rather ignominious end.

Slide of

Slide of

Presidential hopeful

South Bend was very much a company town and it was hard hit when 6000 Studebaker auto-workers lost their jobs overnight. It took decades to recover, and even today poverty levels are above average. One big positive continues to be the University of Notre Dame, which is one of the best colleges in America.

Another factor that put the city in the news was its mayor between 2011 and 2019, Pete Buttigieg. He made a bid for the presidency in 2020, and while unsuccessful, is currently Secretary of Transportation.

PICTURE: Buttigieg gets into a Studebaker Lark in 2019, announcing “My kind of ride” on Twitter

Slide of

Slide of

Today

Nearly 60 years on, traces of Studebaker and its cars remain in Indiana. Apart from the abandoned factory site, parts of which have been refurbished for new uses, the company’s test track located 15 miles west of South Bend still operates. Originally acquired by Bendix when Studebaker quit automaking, it went to Bosch in 1996. Navistar - today a part of Volkswagen - bought it in 2015 and still operates it today to test its heavy trucks.

Today the main organization burning the company’s candle is the Studebaker National Museum, located in South Bend. One floor tells the story of the wagon-making days of the company, while the other two floors are all about its automaking and military days. Highlights include a Studebaker carriage used by Abraham Lincoln, an early 1902 electric Studebaker, and various military vehicles built by the company from both world wars. It’s a suitable celebration of a great American company that like so many other lost marques, found it hard to compete against the economies-of-scale enjoyed by America’s largest auto firms.

Access control:

Open