How many times have you read a manufacturer describe the cabin of its new car as being “inspired by a fighter jet cockpit”? Virtually all sports car makers have trotted out that phrase at one time or another.

It’s a good marketing line, but what is actually meant by it? Does it mean that, to use the dreadful cliché, the controls fall readily to hand? That all the important instruments are in line of sight? Or what? Well, it’s time to put a cap on this nonsense.

I decide I will ring BAE Systems, maker of the Typhoon fighter, and ask if I can speak with the people who actually design fighter cockpits. Better still, perhaps I could bring a modern sports car for them to have a look at and get them to judge it for fighter cockpit-ness.

And so a couple of weeks later – thanks to the miraculous organisational skills of BAE PR man David Coates – photographer Stan Papior and I are thrashing up the M6 to BAE System’s Warton factory near Preston in a Jaguar F-Type roadster. This is going to be a very good day out.

Head of the cockpit group is 49-year-old Miles Turner, who has been with BAE since leaving school but has been leading the cockpit team for the past three years. With him is colleague Paul Chesham, who’s 40 years old and studied aeronautical engineering at Loughborough and followed that up with an MSc in ergonomics.

To my amazement, the large open-plan office in which we meet Turner and Chesham is devoted to cockpit design, because the Typhoon’s interior is continually being upgraded and improved by the 28 boffins in the team.

We’re not able to sit in a real Typhoon cockpit, but we do have a Typhoon simulator and a mock-up cockpit that Turner and his colleagues use as a day-to-day tool. In the simulator, everything works as it does in the real aircraft.

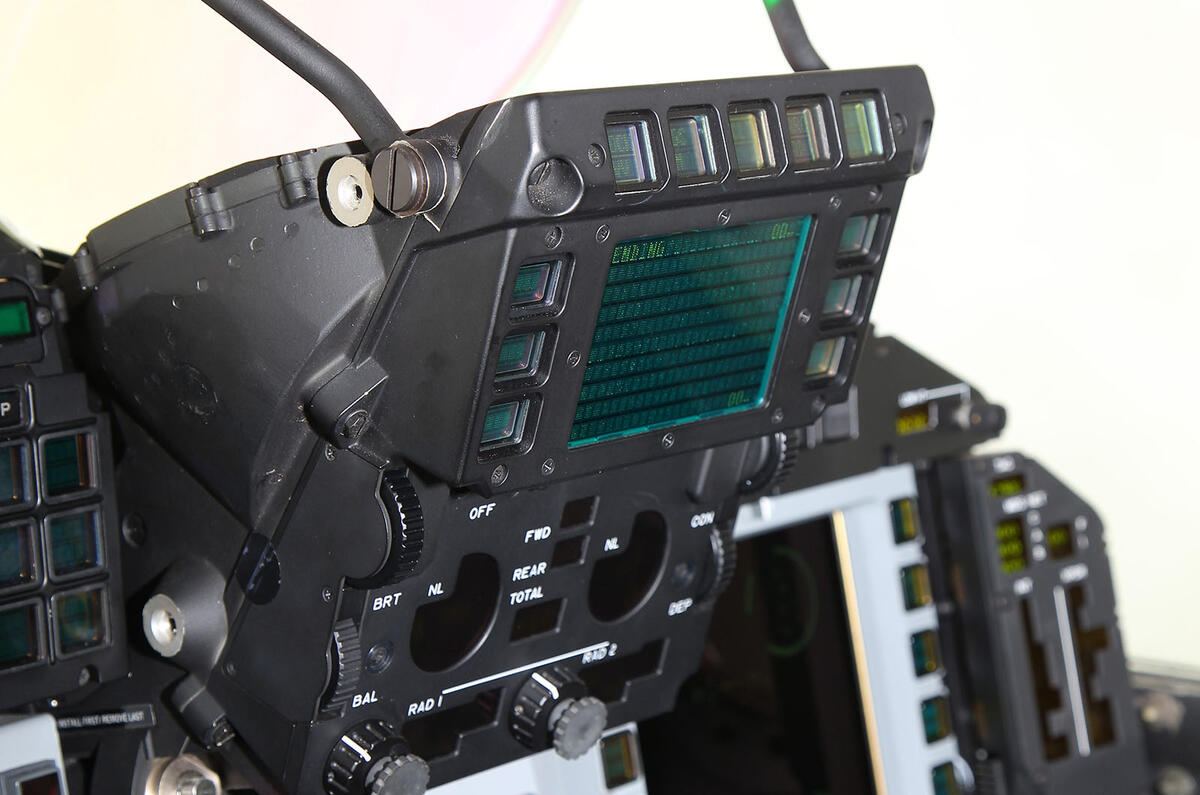

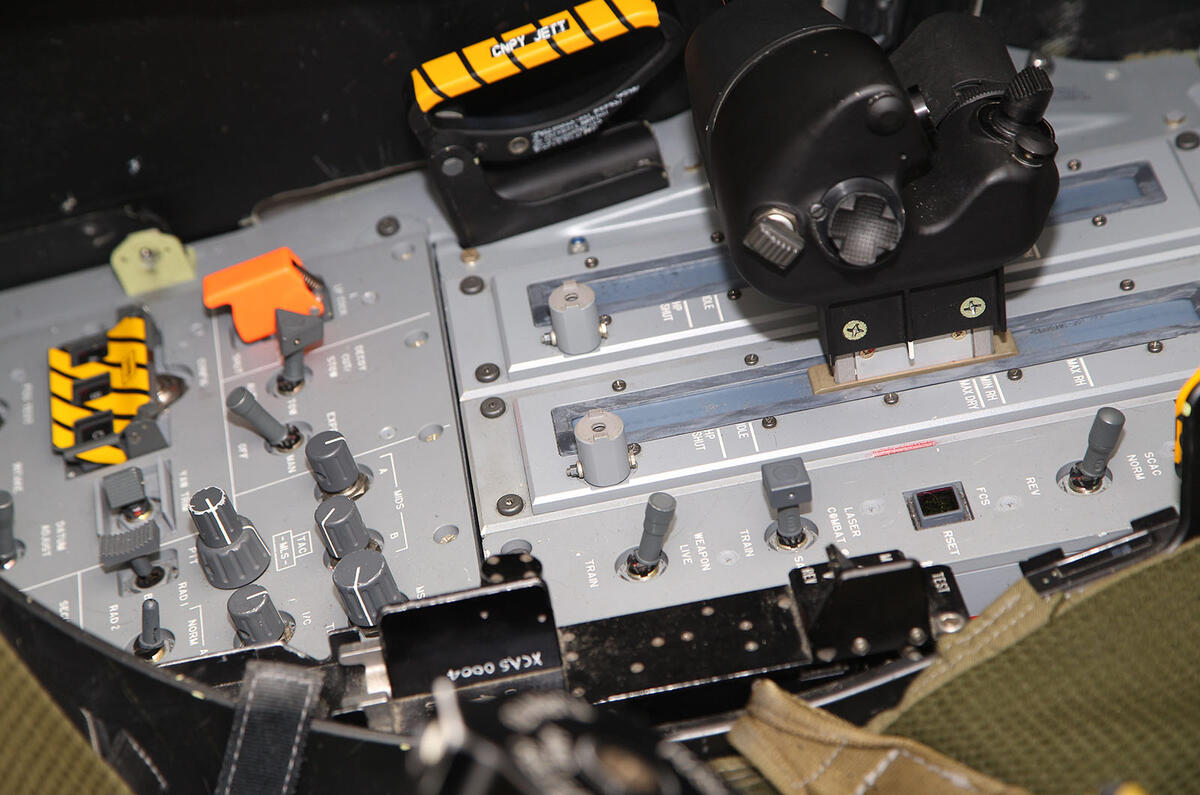

Dear God, it looks complicated. In front of me are three screens, each surrounded by unmarked buttons. Between my legs is a joystick that’s bristling with buttons and switches. “The joystick,” explains Chesham, “has 130 separate functions. It didn’t have that many on the first Typhoons, but we’ve kept adding to it.”

The cockpit is snug but not uncomfortable. To each side of me, there’s a long panel containing switches and buttons which stretches behind my back so that I can’t even see some of the controls.

“The idea is that the primary controls or the most important ones are to the forefront and the less crucial ones are out of the way,” explains Turner. “The other key point is that we try to group functions together, such as communications and the radio controls.” Sure enough, I can vaguely recognise knobs and switches that work the radios.

Many of the switches and knobs have designs that look influenced more by Bassett’s Liquorice Allsorts and Dolly Mixture than aviation’s history. “Because many of the controls are out of the pilot’s line of sight,” explains Chesham, “he has to be able to identify them quickly and accurately by feel.”

The three screens can each display a baffling amount of information, with the choice of which of them displays what being variable; for example, you could put information about the engines’ performance on any of the three screens.

The pilot can scroll across all the displays using a cursor controlled by a ‘coolie hat’ switch on the joystick. Turner and Chesham explain that flying the Typhoon is actually pretty straightforward. The tricky bit is operating all of the systems, and making this easier for the pilot is what their job is all about.

The most obvious crossover between a fighter jet and a car is the head-up display, or HUD. The only difference is that in a car, you get speed, time and perhaps directions to the local chippy, whereas in the Typhoon, you’re presented with a huge amount of information spread across virtually the whole windscreen.

Target selection, interception details, speeds, times and a multitude of information can be displayed. Now I am beginning to understand why the selection process for fast jet pilots is so rigorous and why so few make the grade.

Time for Turner and Chesham to have a sit in our F-type. By chance, the week before coming up to Warton, I’d met Jaguar design boss Ian Callum and told him what we were up to. “Has the design of fighter cockpits influenced your work?” I asked.

“No, but some of my designers talk about it,” Callum said. “But the switch that selects the driving mode in the F-type is the same design as the one in the Typhoon that selects ‘economy’ mode.”

A nice fit, but unfortunately it’s news to Turner and Chesham, because there is no such switch on the Typhoon. “The obvious difference between a car and a combat aircraft,” says Turner, “is that in a car, style takes preference over function. For us, it’s all about function and ergonomics.”

Both men agree that although the Jaguar’s cockpit looks great, it has virtually nothing in common with a fighter jet’s. And I’d lay money on them saying the same thing about the cabin of any other sports car.

There’s an interesting point to be made here: the modern car is getting more complicated, with manufacturers throwing more ‘infotainment’ features such as apps and internet access at drivers in what, I suspect, is an attempt to woo younger buyers. It is illegal to hold a phone handset to the ear but not to operate more and more complicated systems while on the move.

I suspect that today, there are far more accidents caused by eyes being inside the cabin rather than on the road than current statistics show.

If the level of equipment and functions fitted to cars continues to increase, I reckon car interior designers will have to place a greater focus on ergonomics and function than on style. Mind you, there’s nothing unsexy about the Typhoon’s cockpit.

Get the latest car news, reviews and galleries from Autocar direct to your inbox every week. Enter your email address below:

Add your comment

Ergonomics, a word that seems

Also, the fashion for high waistlines, tiny rear side windows and large areas of portrait-black around all glass means that parking manoeuvres are becoming progressively more difficult.

Rear-view cameras are being deployed on some higher-spec models, but they don't make up for the human eyeball.

And I bet that Jaguar weekly,

papagomp wrote:And I bet that

Hahaha.

"While the Eurofighter is faster, handles better and covers distance more quickly its poor fuel economy means the Jaguar is our choice."

Marketing