The incentives to buy an electric car in the UK may have been reduced, but more and more people are still making the switch away from conventionally powered vehicles.

So far this year, sales of ‘alternatively fuelled’ vehicles have accounted for around 4% of all new car registrations.

Britain is western Europe’s third-largest market for electrified cars, behind the Netherlands and Norway, where incentives are substantial, but the global trend tells a similar story.

March this year was the third-best month for electrified car sales in Europe, behind only December 2015 and 2016, when financial inducements peaked. The new Renault Zoe and the Nissan Leaf were the standard-bearers, chased by the plug-in hybrid Mitsubishi Outlander. Electrified car sales average around 1% of total sales across the region.

In the US, the mindset is anchored harder in big-bore petrol engines, but the signs of a shift towards EVs are still encouraging. In the first three months of this year, led by Tesla but boosted by ongoing sales of the Leaf and the new Chevrolet Bolt, fully electric cars accounted for more than 1% of sales for the first time, a year-on-year rise of 74%. Sales of hybrids are growing at a similar rate.

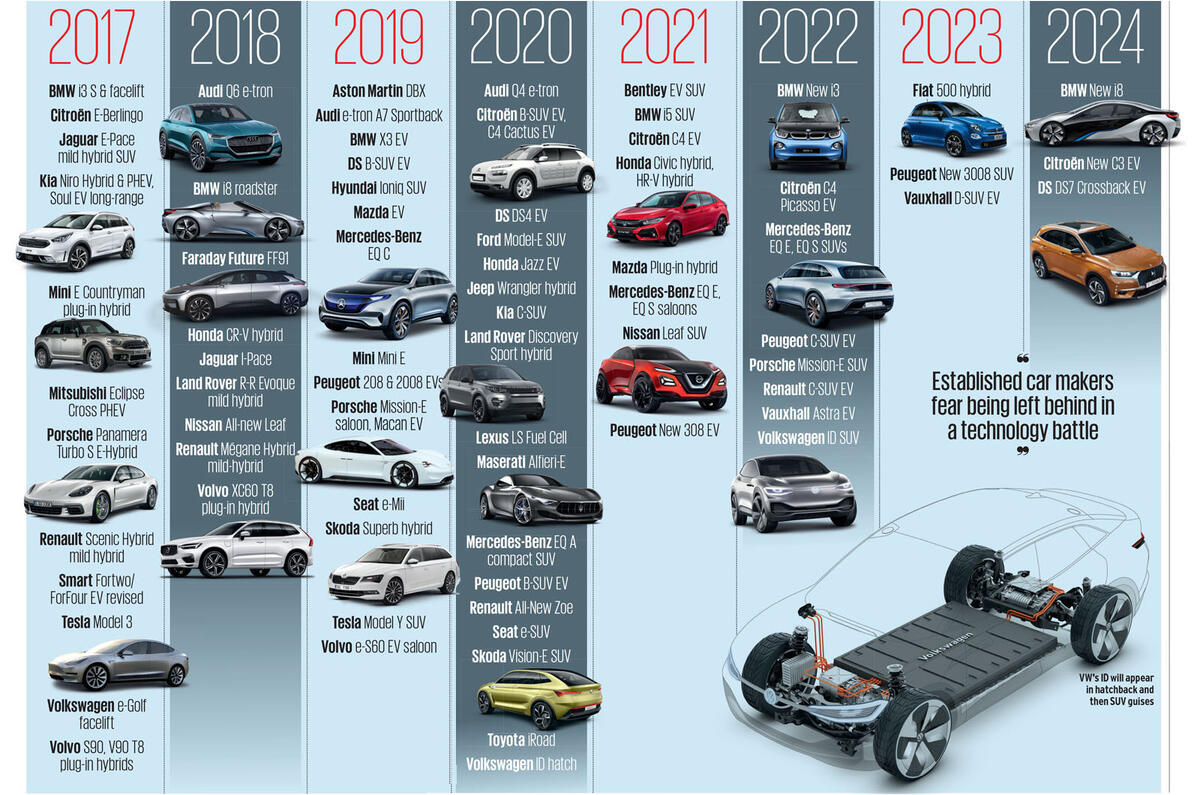

Little wonder, then, that the table to the right highlighting the EV plans of the established global car makers is jampacked. Despite a veil of secrecy over future products, Autocar has uncovered at least 100 new EVs and hybrids due to be launched in the next eight years as the shift to electrified powertrains takes hold. Using published sources and industry contacts, the multi-billion pound investment plans of the car industry to launch large numbers of battery electric and hybrid models is laid bare.

And yet in Europe and the US this growth is more of a creep than an avalanche, and even the most ambitious projections can’t account for the levels of money being invested to develop these cars. For comparison, fewer than 4000 Renault Zoes were sold in Europe in March, compared to just under 48,000 Ford Fiestas. Furthermore, profit margins, even on big-ticket Teslas, are said to be waferthin, to the point of making any hope of a return on investment unlikely for years to come.

So what’s driving this trend? Firstly, and most publicly, the much-heralded emissions targets, led in Europe by the EU’s fleet-average CO2 target of 95 g/km in 2021 and then the next target — possibly as low as 70g/km — by 2025. The regulations are broadly echoed around all global markets, albeit to varying degrees, and underline that legislators and public health officials are determined to reduce carbased emissions come what may. Whether or not there is public demand for the cars they make, manufacturers cannot afford to flout the rules. Even so, that doesn’t explain why many are jumping into the technology wholesale.

However, the real driver behind the development is what’s happening in China, and the huge potential there for sales of electrified hybrids and pure-electric cars. It’s not just about good business, either; established car makers that ignore China’s drive towards EVs also fear they could be left behind in a technology battle that, should they lose, could leave their grip on other markets vulnerable to attack.

Why is China pushing so hard for EVs? Apparently motivated by a need to reduce its heavy industry-driven pollution, Chinese officials are in fact determined to break out of the dependence on imported oil, a natural resource the country is famously short of. At the same time, the aim is to take advantage of a once-in- 100-year powertrain shift in order to leapfrog established car makers. By encouraging its home car makers, such as SAIC, Geely and Trumpchi, to focus on electric powertrain technology, China sees an opportunity to build a thriving domestic car industry with the ability to sell credible Chinesemade cars internationally. It is a plan that was born more than a decade ago but which is only now coming to fruition.

This was confirmed last month when China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) released a road map for future transport. Last year over 28 million cars were sold in China, marking another year of double-digit growth and leaving the US’s sales of 17.5m in its wake. By 2025 MIIT is predicting that China’s sales will hit 35m, and crucially it has suggested that it wants 20% of that total to be made up of so-called New Energy Vehicles (NEVs). That equates to sales of around 7m electric cars, which represents quite a shift given that fewer than 2m are estimated to have been sold globally last year (the vagaries of reporting between markets make exact figures hard to determine).

That 20% figure also suggests that MITT wants most of China’s new car sales growth until 2025 to be in EVs, and history has shown that Chinese government ministries tend to get what they want.

Such a shift would be pivotal for the take-up of EVs and underlines why so many established car makers have been content to let disruptors such as Tesla lead up until this point, before launching a raft of their own products as opportunity knocks.

In parallel, China has been getting the health of its domestic car makers in order, amalgamating some of the weaker firms with larger ones, pushing improved product offerings and driving knowledge-sharing by forcing joint ventures with Western brands. Chinese makers have a healthy 45% share of the vast home market today, albeit focused on the lower end of the price scale. Even so, in a country so vast, that’s enough to generate the profits needed to invest in R&D and consider the global expansion that has long eluded its car makers despite a number of launches in the US and Europe.

The impact of these policies for established global brands is double-edged. There’s an opportunity to sell vast numbers of EVs in China, but the country’s rules on joint ventures mean any success is tempered by the threat of the profits generated and the expertise gained by a Chinese partner in the process. This could in turn give the country’s car makers an opportunity to develop better EVs, be it with a longer range or for lower prices, for a global market. How seriously this threat is being taken is highlighted by Toyota and Honda’s announcement that they will, after all, make pure-electric cars.

As recently as 2013 Toyota spoke openly about the limits of electric cars, reasoning that hybrid technology was the only practical and cost-effective bridge to the adoption of hydrogen powertrains. At Honda, it was a similar story. Yet fast-forward four years and both manufacturers have EVs in the pipeline, with Toyota’s division led by CEO Akio Toyoda. The reason is China’s anticipated plan to declassify hybrids as NEVs, which would leave both Japanese brands lagging in the world’s biggest car market — and that’s a risk simply too great to contemplate.

How this plays out will be fascinating to watch and should inform our understanding of why the established car makers are moving so fast towards electrification. Never before has it been so important to view the machinations of the car industry from a global rather than regional perspective. In this context, Volkswagen’s post-Dieselgate goal of selling 1m electric cars a year by 2025 doesn’t sound so crazy, and neither does Jaguar’s decision to launch the I-Pace despite insiders admitting that sales targets could initially be limited to just a few tens of thousands.

Whether it is forced or natural, the demand from consumers in China will drive the market, and the incentive is there for a battle royale between the established car manufacturers and China’s home-grown brands.

Read more:

MG E-Motion EV sports car for production in 2020

Jaguar I-Pace: first drive of electric SUV concept

Mercedes EQ concept: first drive

Jim Holder and Julian Rendell

Join the debate

Add your comment

Infrastructure and taxation will impact Global addoption of EVs

The Chinese have there established strategy to gain competitive advantage through early adoption of EV technology and thereby enable economically viable entry into the mature automotive markets. Equally the established brands are fully aware of the need for EV product to defend their share of the 25m plus Chinese market. However, there is growing pressure in Europe and the USA for cleaner transort, especially within Cities and urban areas. By 2025, there will be no go areas for ICE vehicles, particularly in regard to personal mobility.

Government will have to invest in electricity generation and distribution to enable 20% of new car sales to be EVs, even if they are recharging overnight when traditional demand is low. Equally government doesn't want to lose the automobile as a revenue stream, therefore, a new digital road use formula will probably be adopted, at a significant cost.

There will be some other down sides, such as a likely increase in distribution costs of petrol and diesel when demand starts to decline. Some brands may disappear due to the costs of adopting the new technology.

On the positive side, we should have a cleaner environment, however battery disposal may be an issue, and EV platforms lend themselves to autonomous vehicles particularly well.

Whatever, this will be a decade of greatest turmoil the industry has experienced and should fuel some great advances.

Greater electricity generation capacity will be needed globally?

Is the infrastructure there to cope?

I thought we were borderline for electricity generation already?

Have established car makers really 'let' Tesla take the lead?

Is it perhaps more likely that they were blindsided by the success of the Model S, which has taken significant sales in the luxury sector, and have been struggling to catch up ever since?

To any long-term observer of the automotive sector, this seems far more likely as a scenario.

But obviously Autocar needs to flatter its advertisers.

Perhaps this is why Autocar keeps focussing on the market share of EVs, when the more meaningful statistic is the year on year growth. This growth is significant and goes a long way towards explaining why so many new EVs are in the pipeline.