Slide of

Slide of

Many of the companies that left a mark on the history of Germany’s automotive industry are no longer around to tell their story.

That’s where the Deutsches Museum Verkehrszentrum comes in. Located near the heart of Munich in scenic Bavaria, it’s home to hundreds of significant cars, scooters, motorcycles and trains built since the 1800s. Most of the cars displayed in the museum are German but there are some exceptions to the rule, including a Lancia Lambda and a Tatra T87. Join Autocar for a virtual stroll through the collection’s highlights:

Slide of

Slide of

Panhard & Levassor (1891)

Panhard & Levassor gets credit for several important innovations that moved the automobile into the 20th century. It built the first-known car with a front-mounted engine in 1891, four years before Autocar published its first issue. Though French, it perhaps helps its presence in the museum that it features an engine from Germany's Daimler.

Moving the engine to the front improved cooling, weight distribution and handling. It also made the car safer; early cars with a rear-mounted engine tended to lift their front axle when pulling away from a stop. Many rival automakers followed Panhard & Levassor’s example as cars became more powerful.

Slide of

Slide of

De Dion-Bouton Quadricycle (1899)

De Dion-Bouton’s Quadricycle adopted a curious layout. Two passengers rode on a bench seat mounted over the front axle while the driver sat behind them on a saddle and used handlebars to steer. It was a brave but senseless attempt at building a car because the passengers obstructed the driver’s view of the road ahead. De Dion-Bouton quickly concluded it made more sense to place the driver in front of the passengers, not the other way around.

Slide of

Slide of

Opel Patentwagen (1899)

Opel began making sewing machines shortly after its inception in 1862 and added bicycles to its catalog in 1886. It made its first car, the Patentwagen, after purchasing Anhaltische Motorwagenfabrik in 1899. Power came from a single-cylinder, 1.5-liter engine that sent 4hp to the rear wheels via leather belts. Opel made 65 examples of its first car.

Slide of

Slide of

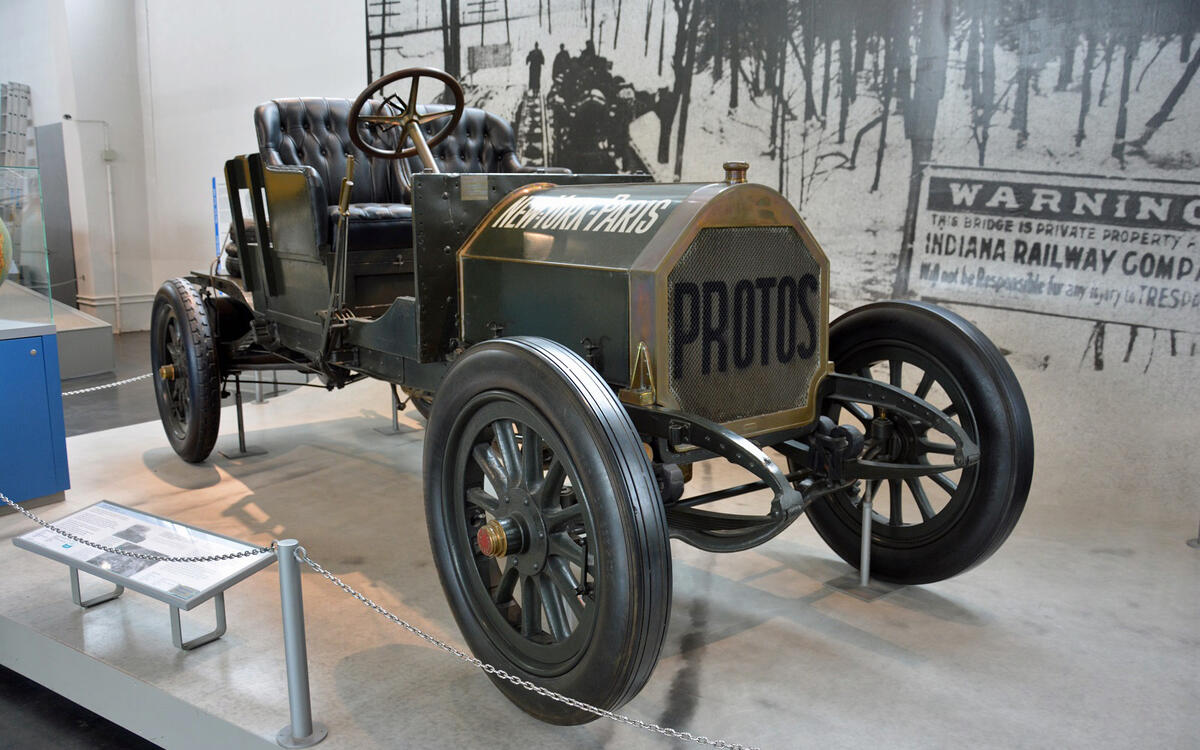

Protos Racer (1907)

This 1907 Protos Racer participated in the Great Race held in 1908. It left Times Square in New York City on 12 February 1908 and spent five and a half months driving 21,278km (13,221mi) to reach Paris after trekking across North America, Asia and a big chunk of Europe.

The German team driving the Protos arrived in the French capital four days before the second-place car but it lost the race after receiving a 30-day penalty for allegedly putting the car on a train for a portion of the event.

Slide of

Slide of

Adler Landaulet (1911)

There were many parallels between early luxury cars and the horse-drawn carriages they shared the road with. Made in 1911, this Adler Landaulet placed the chauffeur in an open compartment, exposed to the elements, and the passengers in a separate compartment with doors and windows. Called landaulet, this body style came directly from the carriage industry.

Slide of

Slide of

Audi Alpensieger Type C (1914)

Audi founder August Horch drove the Type C pictured here to first place in the 1914 Austrian Alpine Rally. It wasn’t a sports car and it didn’t need to be; crossing the Alps in the 1910s required a rugged, solid car with a decent amount of off-road capacity and a powerful engine, not one capable of reaching high speeds.

Horch drove the Type C (which he later called Alpensieger, ‘Alpine Victor’ in German) for 19 years after the race. He painted his wife’s name, Anneliese, on the back end of the car.

Slide of

Slide of

Slaby-Beringer electric car (1920)

SB-Automobil developed a small electric car for disabled war veterans. Light and excruciatingly basic, it used a battery-powered drivetrain which provided 60km (37mi) of range. Interestingly, the steering arm swiveled out to make the car easier to push if it ran out of electricity.

In an odd twist of fate, SB-Automobil sold a majority of the production run to Japan, where the cars were often used as government vehicles. The company shut down in 1924 after an earthquake destroyed a large shipment of cars.

Slide of

Slide of

Rumpler Tropfenwagen (1922)

Edmund Rumpler believed he could apply the basic rules of airplane design to create the world’s most aerodynamic car. He succeeded. Introduced in 1921, the Tropfenwagen had a drag coefficient of 0.28. To add context, the Porsche 918 Spyder posts a drag coefficient of 0.29. The trade-off was that it looked like a cross between an airplane, a submarine and a boat.

Slide of

Slide of

Rumpler Tropfenwagen (1922)

Though undeniably innovative, the Rumpler Tropfenwagen remains unknown as if it had never existed. Motorists with zero interest in aerodynamics found its design interesting but wrong. It didn’t have a cargo compartment and its complicated engine – six cylinders arranged in a W configuration – rarely ran well. Berlin-based film company UFA bought the last cars made and set them on fire in the 1927 film Metropolis.

Slide of

Slide of

Lancia Lambda (1923)

Vincenzo Lancia tapped into the expertise he acquired building race cars to develop the Lambda. Introduced in 1922, it stood out with unibody construction and a 49hp V4 engine. It weighed much less than many comparable models, its center of gravity was lower and it offered an independent front suspension. Overall, it’s an early example of a driver’s car.

Slide of

Slide of

Krupp street sweeper (1924)

As population grew and traffic increased, city governments around the world faced the increasingly daunting task of keeping streets clean. Germany’s Krupp stepped up to the challenge of providing a modern solution.

The company boasted its street sweeper could perform the work of two horse-drawn sweepers or 60 workers. The three-wheel layout greatly reduced its turning radius.

Slide of

Slide of

Opel 4/12 PS (1924)

Opel found itself unable to sell large, expensive cars after World War I. It consequently expanded its line-up with a smaller model named 4/12 PS that it could sell for a fraction of the cost of its more luxurious cars. It was only offered in green, a decision which earned it the nickname laubfrosch (‘green frog’ in German). Opel made 120,000 examples of the car.

The 4/12 PS bore more than a passing resemblance to the Citroën 5HP. Citroën unsuccessfully filed lawsuits against Opel in 1926 and 1927.

Slide of

Slide of

Alfa Romeo 6C Gran Sport (1931)

Famous Italian pilot Tazio Nuvolari owned and raced this 1931 Alfa Romeo 6C Gran Sport until it encountered engine problems. Those who saw it race wouldn’t recognize it, though.

Engineer Walter Freund purchased the non-running car and immediately removed the original body. He kept the chassis and added a surprisingly aerodynamic body he designed on his own, though he borrowed several styling cues and the basic proportions from the Wanderer W25.

Slide of

Slide of

DKW F1 (1931)

DKW asked Audi’s engineering department for a small, affordable roadster in 1930. It took only a few weeks for the team in charge of the project to develop the F1. It stood out from other DKW models built during the same era because it adopted front-wheel drive, a technology that was relatively new at the time but that later spread across the company’s line-up. The layout made the F1 lighter and cheaper to build than a comparable rear-wheel drive roadster.

Slide of

Slide of

Goliath Pionier (1931)

Goliath aimed to put Germany on wheels with the Pionier, a three-wheeler built on a chassis made of wood. Imitation leather upholstery covered the body while the cabin offered space for two passengers in a relatively cramped space. The 198cc engine represented the car's main selling point. It was exempt from road tax and it could be operated without a driver’s license. Goliath made about 4000 examples of the Pionier.

Slide of

Slide of

Auto Union Type C (1936)

Ferdinand Porsche developed the Type C for Auto Union. Designed exclusively for racing, it used a mid-mounted V16 engine that made 520hp in its most basic configuration. The Type C could reach 340kph (211mph), a jaw-dropping statistic at the time and one that remains impressive in 2018. It won 10 of the 17 grand prix races it entered in 1936.

Slide of

Slide of

Steyr Type 50 (1936)

Made in Austria, the Steyr Type 50 could have become the Volkswagen Beetle’s most direct competitor. It stemmed from a project launched in 1934 to develop a production-ready people’s car should a major manufacturer demand one on short notice. Its basic shape echoed the Beetle’s but, as the sizable grille suggests, it received a water-cooled four-cylinder engine mounted in front of the passenger compartment.

The Type 50 never reached production.

Slide of

Slide of

Adler Diplomat 3GS (1938)

Fuel shortages during World War II brought wood gas generators back into the spotlight. The system could be fitted to most production cars and trucks, though it required a number of modifications. It consisted primarily of a stove often attached to the back or the side of the car, a filter and a radiator all connected by a network of metal pipes.

Motorists fed the stove with wood, charcoal or both depending on the system and started a fire. Smoke traveled through the pipes until it reached the filter and the radiator up front. It then entered the combustion chamber. The engine ran on carbon monoxide and hydrogen.

Slide of

Slide of

Adler Diplomat 3GS (1938)

Fitting a wood gas generator had a dire effect on performance. The Adler Diplomat 3GS’ straight-six engine made 60hp stock and the car could cruise at 100kph (62mph). Running on wood gas lowered the six’s output to 36hp and reduced the Diplomat’s top speed to 70kph (43mph).

The driver could drive for up to 100km (62 miles) on a load of wood. Wood-filling stations popped up across Europe to keep cars moving during the Second World War. Motorists walked away from wood gas generators soon after the war and never looked back.

Slide of

Slide of

Tatra Type 87 (1940)

In the 1930s, Germany’s network of smooth, fast highways gave automakers the freedom to design passenger cars capable of reaching higher speeds than ever before. Though Tatra was Czech, Germany occupied its factory during the war and forced it to adapt to the German market. Fritz Todt, the man responsible for highway construction in Germany, called the Type 87 the Autobahn car.

The sleek design gave it a 0.36 drag coefficient, the same figure achieved by the Ferrari Testarossa 46 years later. Power came from a rear-mounted, air-cooled V8 engine that made 72hp. Tatra made about 3000 examples of the Type 87 between 1936 and 1950.

Slide of

Slide of

Messerschmitt KR 175 (1954)

The BMW Isetta has become the poster child of the short-lived bubble car segment. It wasn’t the first or the only car of its kind, however. Messerschmitt introduced the three-wheeled KR model in 1953.

It occupied the space between the scooter and car segments with a small, lightweight body topped by a transparent plastic roof and a 173cc engine that churned out 9hp. Introduced in the right place at the right time, the KR found over 50,000 buyers during its 11-year production run.

Slide of

Slide of

Glas Goggomobil T 250 (1954)

Glas expanded its business beyond agricultural machinery when it began producing the Goggomobil T 250 in 1954. The line-up included the two-door model pictured here and a spacious van aimed at delivery drivers in urban areas. Both used the same basic 247cc engine and could be driven by German motorists with only a basic scooter license. This loophole lured over 280,000 buyers between 1954 and 1969, when Goggomobil production ended.

The end of the bubble car era hit Glas hard and BMW took over the battered company in 1966. Though the name and the cars disappeared, the Glas factory in Dingolfing, Germany, still exists in 2018. It produces BMW’s 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8 Series models plus components for the electric i3. It even makes bodies for Rolls-Royce - quite a step up from post-war bubble cars.

Slide of

Slide of

Messerschmitt KR 200 Super (1955)

The Messerschmitt KR 200 proved bubble cars could also be driver’s cars. Fritz Fend, the engineer who developed the KR, drove the example pictured here for 24 hours on the Hockenheimring track in 1955. He set 25 speed records in his category, including an all-out speed record of 138kph (85mph).

Though derived from the production model, the record-breaking KR 200 used a 13.5hp evolution of the standard car’s 10hp, single-cylinder two-stroke engine. Fend also shed weight by removing the roof and he designed a more streamlined body.

Slide of

Slide of

BMW Isetta (1957)

Though it’s not eligible for the coveted ‘ultimate driving machine’ label, the Isetta earns credit as the car that saved BMW from collapse. The Munich-based company purchased a license to manufacture the Isetta from Italy’s Iso and made several changes to the car, including replacing the two-stroke engine with a four-stroke unit. The basic design with a front-hinged door and a two-person bench seat remained.

Demand surpassed supply. BMW built 160,000 examples of the Isetta between 1955 and 1962. Its success helped fund the development of the New Class models introduced in 1962.

Slide of

Slide of

Heinkel Kabine (1957)

German aircraft manufacturer Heinkel jumped into the bubble car segment in 1956 with an Isetta competitor designed in-house. Named Kabine, it followed a similar format with a front-hinged door but it weighed less than its BMW-badged rival and it offered a pair of small rear seats suitable for young children. The surprisingly versatile four-seater used a 10hp, 196cc single-cylinder engine borrowed from Heinkel’s Tourist scooter.

Slide of

Slide of

Heinkel Kabine (1957)

Heinkel built the Kabine until 1958 and allegedly lost money on every example it sold. The model was briefly made under license in Ireland by the Dundalk Engineering Company in 1958 but Heinkel quickly ended the deal due to concerns over quality control. British company Trojan Cars bought the license to manufacture the car in 1960 and sold it as the Trojan 200 until 1966. Both three- and four-wheeled models were made during Kabine’s 10-year production run.

Slide of

Slide of

Victoria 250 Spatz (1957)

The pantheon of automotive history is full of little-known manufacturers that, for various reasons, disappeared after making a small batch of cars. Germany’s Victoria illustrates that cycle well.

The Victoria 250 came to life in 1955 when two friends built a small roadster with a plastic body and a 200cc single-cylinder, two-stroke engine. Victoria – a German firm that made bicycles and motorcycles – bought the rights to manufacture the model a year later and upgraded it with a 245cc engine bolted to an improved transmission.

Slide of

Slide of

Victoria 250 Spatz (1957)

The 13.8hp engine sent the 250 Spatz (a term which translates to ‘sparrow’ in German) to a top speed of 90kph (about 55mph). Victoria made roughly 1600 examples before pulling the plug on the project. Not many survived, but the example in the Deutsches Museum remained in service for over four decades.

Slide of

Slide of

Mercedes-Benz 220 S (1959)

Mercedes-Benz began crash-testing its cars in 1959. Early on, the company used either a winch or a steam rocket to pelt cars against a concrete barrier. This system worked, as evidenced by the 220 S’ crumpled sheet metal, but it wasn’t precise and Mercedes had a difficult time controlling the speed of the impact.

The 220 S pictured above crashed at approximately 48kph (29mph). The front end absorbed the brunt of the impact while the cabin remained intact.

Slide of

Slide of

BMW 2600 L (1963)

Introduced in 1954 as an evolution of the 501, the BMW 502 stands out as the first German passenger car powered by an eight-cylinder engine. The 2.6-liter V8 made 110hp in its most basic configuration and allowed the car to reach 164kph (101mph) on the unrestricted sections of Germany’s Autobahn. The 502 became the 2.6 in 1958 and the 2600 in 1961. The L suffix denoted a more luxurious model.

The Deustches Museum’s 2600 L was built in 1963. It was owned by Munich mayor Hans-Jochen Vogel between 1965 and 1970 and sold to the museum in 2010.

Slide of

Slide of

NSU Spider (1964)

During the 1960s, NSU spent a fortune developing and fine-tuning Felix Wankel’s rotary engine. It tested the unit in a Prinz, its entry-level model, and later brought it to production in the Spider. The single-rotor engine made 50hp and sent the convertible to an impressive top speed of 150kph (93mph).

Mechanical problems largely overshadowed the Spider’s performance credentials. NSU ended production after making 2400 examples. It continued investing money in Wankel technology and nearly collapsed after several costly but unsuccessful attempts at bringing it to the mainstream.

Slide of

Slide of

Porsche 911 S with a stainless-steel body (1967)

Porsche built this experimental 911 S with a stainless-steel body in 1967 as a way to test the material’s suitability for use in a car. The prototype covered 150,000km (93,000 miles) during its seven years on the road. Porsche never launched a production car with a stainless-steel body but it has used the material to make wheel covers and trim pieces, among other parts.

The DeLorean Motor Company picked up where Porsche left off when it introduced the ill-fated, stainless-steel-bodied DMC-12 in 1981.

Slide of

Slide of

Volkswagen Karmann-Ghia Type 34 (1968)

The Type 34 Karmann-Ghia remains one of the lesser-known cars made by Volkswagen in the 1960s. It existed alongside the more common, Beetle-based Type 14 Ghia between 1962 and 1969 but it shared its platform with the Type 3. Volkswagen made it more luxurious (and correspondingly more expensive) in order to offer a range-topping model.

Sales remained low, partly because Volkswagen never offered the Type 34 Ghia in the United States. In hindsight, decision-makers worried about venturing too far away from the budget-friendly positioning that made the Beetle a smash hit during the 1960s.

Slide of

Slide of

Opel GT2 concept (1975)

Opel presented the GT2 concept at the 1975 Frankfurt auto show. At the time, car companies and enthusiasts worried about the future of the sports car after the oil embargo turned the auto industry on its head. The GT2 concept explored how to keep the segment alive.

Designers penned an aerodynamic silhouette to improve fuel economy. Inside, the GT2 featured an on-board computer and a digital instrument cluster. It remained at the concept stage and Opel axed the GT without a direct successor.

Slide of

Slide of

UNI-Car (1981)

In the late 1970s, the Automotive Research Institute (ARI) in Stuttgart, Germany, built four prototypes to explore what cars would look like in a not-too-distant future. The guidelines laid out by Germany’s ministry of research, which sponsored the project, called for a car that returned good fuel economy and could protect its occupants in a high-speed collision. It also needed to look close to production-ready, unlike some of the safety vehicle prototypes built in Europe and the United States during the early 1970s.

Headlamps mounted under glass panel, a streamlined front end, mirrors integrated into the body and covered rear wheel arches made the car aerodynamic. ARI engineers added wipers for the front side windows and fitted the prototypes with four individual seats surrounded by padding.

Slide of

Slide of

UNI-Car (1981)

The innovations continued beneath the body. The Deutsches Museum's prototype uses a 2.5-liter four-cylinder turbodiesel engine rated at 98hp. It shifts through an electronically-controlled continuously variable transmission (CVT). The suspension consists of self-leveling gas springs.

Side impact protection and foam-filled crumple zones kept the occupants safe. These features sound mundane in 2018 but they were cutting-edge in 1981.

Slide of

Slide of

Mercedes-Benz 240 TD (1982)

Mercedes-Benz used to enjoy a near-monopoly on the taxi market in Germany. About 80% of the cabs operating in West Germany during the late 1960s wore a three-pointed star emblem. Mercedes’ market share diminished as Audi, BMW and, to a lesser extent, Opel entered the competition but the Stuttgart-based firm still reigns supreme in Germany’s taxi industry.

The 1982 240 TD on display in the Deutsches Museum spent 23 years carrying passengers in the Munich area. It accumulated over 1.5 million kilometers (about 800,000 miles).

Slide of

Slide of

Volkswagen Beetle taxi (1990)

The Volkswagen Beetle became Mexico City’s standard taxi cab in 1972. Government officials chose it because it cost less to run than the big, V8-powered American models also available at the time. Taxi drivers often removed the front passenger seat to facilitate the gymnastically challenging task of accessing the rear bench.

In 2002, decision-makers announced all cabs operating in Mexico City needed four doors for safety and practicality reasons. This law drove the final nail in the Beetle’s coffin. The last examples retired from taxi duty in 2012, when their 10-year permits expired. The 1990 example displayed in the Deutsches Museum roamed the streets of Mexico City until 2004.

Slide of

Slide of

Mercedes-Benz 500 SEL (1994)

At first glance, this Mercedes-Benz 500 SEL looks like a run-of-the-mill W140-generation S-Class. It’s actually an autonomous prototype equipped with two wide-angle cameras that scope out the road ahead plus an armada of on-board computers that process data and control the car.

In 1995, the 500 SEL drove from Munich to Copenhagen and back with very little human intervention, though a safety driver sat behind the wheel at all times. It passed other cars on its own and could reach 175kph (108mph).

Slide of

Slide of

Tata Nano (2010)

The Deutsches Museum is one of the rare places in Europe where you can see a Tata Nano. Presented in 2008 as India’s people’s car, the Nano aimed to provide a basic, no-frills form of transportation for motorists upgrading from a scooter. Tata officials believed the Indian market could absorb at least a quarter of a million cars annually and they wanted to export some of the production to Europe. Too basic for its own good, the Nano never lived up to expectations.

Production peaked at 74,527 units during the 2011-2012 fiscal year. Production ended in 2018.

The Munich museum honours some of the best cars from Germany & beyond

Advertisement