For a heads-down sort of academic, obsessed with a 10-year mission to create an all-new high-tech battery industry in Britain, Professor David Greenwood is remarkably hospitable.

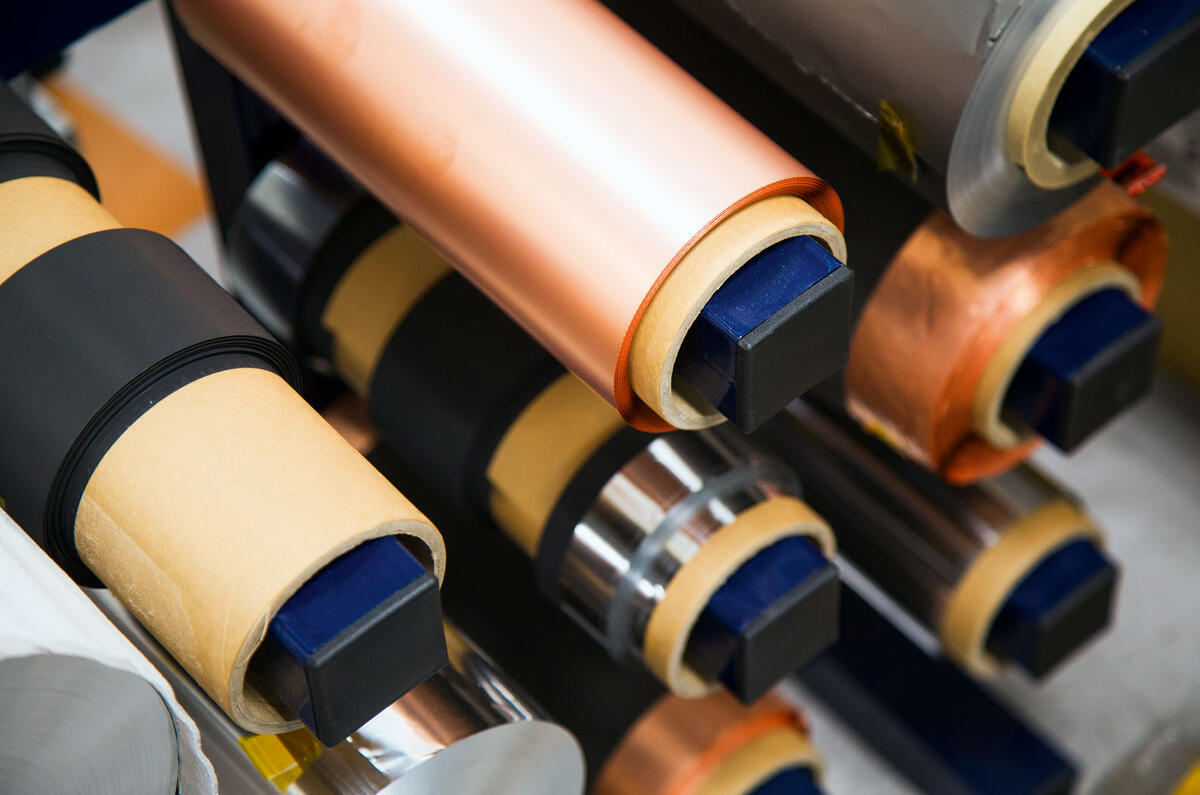

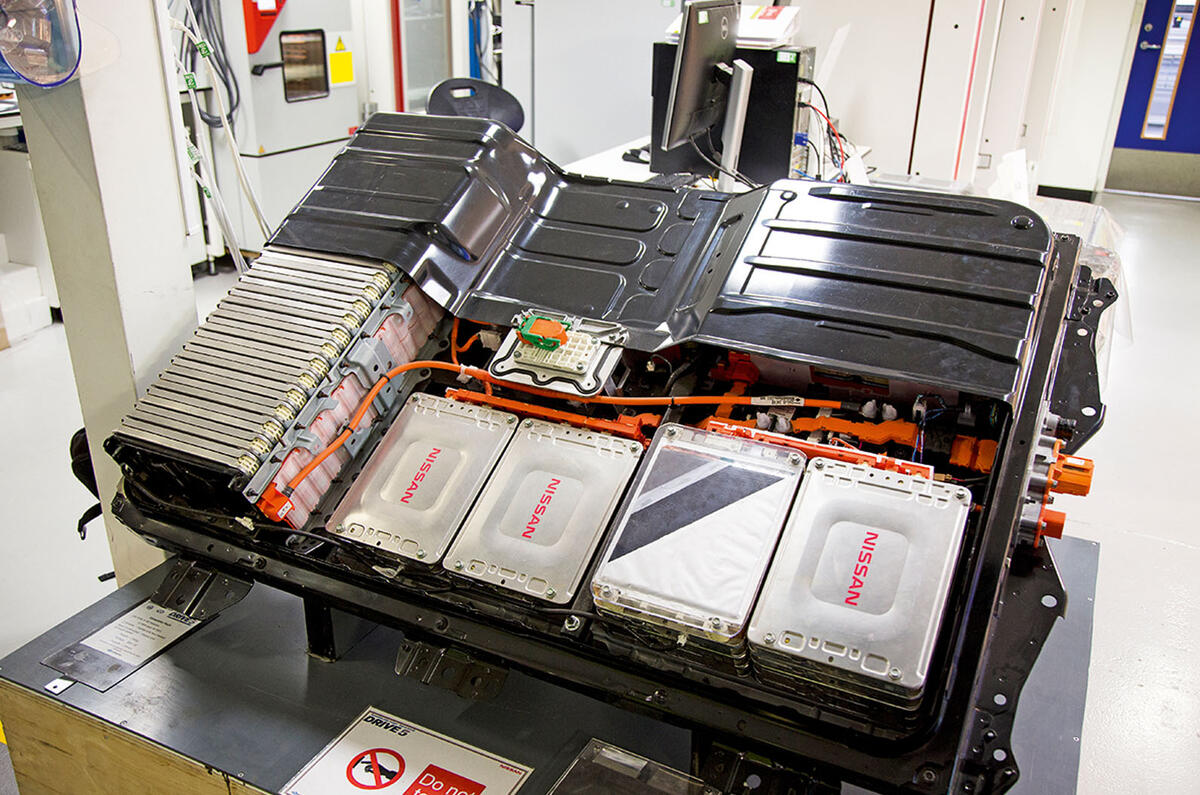

When I meet him in his lair at the Warwick Manufacturing Group (WMG), deep in the heart of the Warwick University Campus, he has just spent hours with a group from a nearby girls’ school, explaining to students what happens inside WMG’s laboratory-cum-battery plant where he and 150 other researchers are not just making better batteries, but also devising processes that will make them affordable and easy to build in the vast numbers our car industry will soon need.

For his sins, Greenwood is one of British industry’s finest explainers, continually drafted into initiatives and seminars, and onto endless technical committees, for his renowned ability to understand new stuff and put succinctly into context for those of us who can’t. Meeting the students is fun, he says, and a vital part of the job.

“Our battery industry is soon going to need thousands of qualified people, and at present we have hundreds,” he says. “These were just the sort of people we’re going to need. The fact that they were young women was salient: automotive manufacturing has been bad at gender balance, which means half the candidates we could be employing we’re not even talking to.”

With little prompting, Greenwood settles into explaining why batteries matter so much, as he has already done once this afternoon.

Join the debate

Add your comment

The simplest solution for the

The simplest solution for the UK Government will be to just slap a VED charge (scuse the pun!) on EVs similar to that for ICEs today.

Standard £140 or whatever with inflation, with a bit more depending on range or overall EV weight. The idea they're actually going to pay for some kind of infrastructure to monitor an EV driver's mileage to collect an EV VED seems a non starter to me.

Lord Bhattacharyya set up WMG

Lord Bhattacharyya set up WMG, so where is his obituary in these publication? He was instrumental in JLR, involved with the Rover Group and key to setting up this battery centre.

He passed away a few days ago.

This is just a "think tank"

This is just a "think tank" & not a production facility. The French & German governments are actively ecouraging companies to set up battery plants in mainland Europe to compete with the Chineese. No sign of that happening in the UK. Whatever ground breaking ideas that WMG will come up with they will probably be bought outright by a foreign company & the manufacturing taken abroad.

The point is to develop

The point is to develop better batteries that can be made in the UK or sold elsewhere, not to mass-produce existing battery technologies...