Slide of

Slide of

Over the last century and a quarter, motoring has become entangled in a web of untruths and half-truths.

It would be nice to be able to demolish all of them, but unfortunately that's beyond the scope of a single article. However, we can at least make a start. In that spirit, here are 15 motoring and motorsport myths which you may believe to be true, along with the 15 reasons why they aren't:

Slide of

Slide of

Americans and front-wheel drive: the myth

Motorists in the United States dislike, and have no interest in talking or even thinking about, cars which are driven through their front wheels. They love rear-wheel drive vehicles, of course, especially if they are fitted with large V8 engines. Four-wheel drive is considered an acceptable alternative for pickup trucks.

Front-wheel drive? Forget it. This is the way it has been, is now, and always will be. Or so you'd think, if you have a cartoonish view of American behaviour.

Slide of

Slide of

Americans and front-wheel drive: the truth

There are a great many front-wheel drive cars on sale in the US today, and on the whole Americans are okay with this. But this is not a modern phenomenon. For example, the Cadillac Eldorado (1976 model pictured) was front-wheel drive from 1967 to 2002, despite at one point having an 8.2-litre V8 engine under the hood.

There were many others too, including the fabulous Cord L-29 of 1929. Three years before model that hit the showrooms, a front-wheel drive Miller racing car won the Indianapolis 500. Americans are very familiar with the layout, and know how to use it. The top three best-selling cars (as opposed to trucks or SUVs) in the US in 2020 were the Toyota Camry, Honda Civic and Toyota Corolla – and all 792,000 examples of them in total are front-wheel drive.

Slide of

Slide of

Aston Martin: the myth

Aston Martin is often said to have been named after one of its founders, Lionel Martin (1878-1945, pictured), and the Buckinghamshire town of Aston Clinton. Martin had very little personal connection with the town apart from winning an event on a nearby hillclimb course which was, and still is, a public road.

Most of this is true, but anyone who tells the story exactly like this is making one significant mistake.

Slide of

Slide of

Aston Martin: the truth

The Martin part of the name does indeed refer to Lionel Martin, but Aston refers to the hillclimb course, which is called (not unexpectedly) Aston Hill, and not to the town.

There is of course a link between the names of Aston Clinton and Aston Hill - too long a story to tell here - but the car company was definitely named after the latter, and not the former.

Slide of

Slide of

Chevrolet Nova: the myth

It is said that the Chevrolet Nova was unsuccessful in Spanish-speaking countries because no va is the Spanish for "it doesn't go". This is presented as fact only in low-quality articles. We can do better than that.

Slide of

Slide of

Chevrolet Nova: the truth

The word “nova”, with the stress on the first syllable, means the same in Spanish as it does in English: the sudden appearance of what seems to be, but in fact isn’t, a new star. No va does indeed mean "it doesn't go", but no functiona ("it doesn’t work”) is probably a better translation in this context. In any case, no va sounds different from nova because the stress is on the second syllable.

Spanish speakers would never confuse the two terms, and would have good reason to be offended if you suggested that they might.

Slide of

Slide of

Drag racing: the myth

Drag racing consists of two drivers racing against each other in a straight line from a standing start. Since the sport was formalised in the early 1950s, the competitive length of the track in high-level events has always been a quarter of a mile (or 1320 feet), followed by a much longer run-off area. In amateur events, runs may take place over an eight of a mile, but the “standing quarter” is the norm in professional racing.

Well, sort of, but anyone who tells you this hasn't been paying attention to the sport for over a decade.

Slide of

Slide of

Drag racing: the truth

Cars fuelled by nitromethane and running in National Hot Road Association (NHRA) events in the US were required to compete over just 1000 feet from partway through the 2008 season, following the death of professional driver Scott Kalitta (1962-2008). The new rule was taken up by other governing bodies around the world in the following years.

Despite the shorter distance, dragsters are now reaching higher speeds at the finish line than they did during the quarter-mile era. The current record is 339.87mph. It was achieved by Robert Hight (born 1969, pictured) in a Chevrolet Camaro Funny Car at Sonoma, California on 29 July 2017.

Slide of

Slide of

Ford Pinto: the myth

In dark corners of the internet you will find people insisting that the Ford Pinto flopped in Brazil because pinto, in Portuguese, is an abusive term. Others, aware that the car was in fact named after a horse, point out that the insult works only in a form of Brazilian slang.

There are also claims that Ford responded to the above by removing the Pinto badges and renaming the car Corcel. There is just one problem with all of this: apart from the bit about Brazilian slang, it ain't true.

Slide of

Slide of

Ford Pinto: the truth

The Pinto did not flop in Brazil, because it was never sold there. Ford's equivalent model for South American markets was called the Corcel, but that was a completely different car.

Furthermore, the Corcel was launched in 1968, two years before the arrival of the Pinto. It could not therefore have been a Pinto with different badging, because time doesn't work that way.

Slide of

Slide of

Hillclimbing: the myth

Hillclimbing is one of the oldest forms of motorsport. Now held at such wildly varying venues as Pikes Peak (US), Shelsley Walsh (UK) and Trento-Bondone (Italy), it is universally agreed to have begun in the late 19th century.

By popular legend, the first event took place between Nice and La Turbie in southern France on 31 January 1897. However, hillclimb historians, who like nothing better than a good argument about their sport, dispute this vigorously.

Slide of

Slide of

Hillclimbing: the truth

The 1897 Nice-La Turbie climb wasn't a standalone event but the final stage of a three-day competition. The finish line was originally meant to be in Monte Carlo, but the final downhill section was made non-competitive for fear of the cars running out of brakes (though one of them nevertheless crashed into the Café de Paris).

If we don't count an event held at Charles River Park in Boston, Massachusetts in October 1898 (which we don't because it was part of an exhibition and the "course" was simply an 80-foot long wooden ramp), the first genuine hillclimb was held the following month at Chanteloup-les-Vignes near Paris. Hillclimb events were subsequently held on the Nice-La Turbie road, but within this definition Chanteloup definitely got there first.

Slide of

Slide of

Mass production: the myth

The Model T Ford (subject of another myth which we'll come to shortly) is often quoted as being the first ever mass-produced car. This appears to make sense, because Ford churned out an enormous number of the things - over 15 million over more than 18 years, which remained a record until Volkswagen finally eclipsed it in 1972.

As we'll see, though, appearing to make sense and actually being true are not the same thing.

Slide of

Slide of

Mass production: the truth

There is no argument that Ford was the first manufacturer to build cars on a moving assembly line. However, the Oldsmobile Curved Dash of 1901-1907 (formally known as the Model R) was put together using interchangeable parts several years before the Model T.

In this case, the assembly line was what we might today call "virtual". Curved Dashes were reportedly moved around the factory on trolleys several times during the process. Other contenders come into play as you relax the definition of mass production. Daimler makes a case that the Benz Velo was the first large-scale production car because more than 1200 examples were built between 1894 and 1902 - a remarkable effort for the time.

Slide of

Slide of

Model T Ford: the myth

In his 1922 autobiography My Life and Work, Henry Ford (1863-1947) wrote that he informed his employees of his decision to concentrate on just one vehicle - the Model T - and added, "Any customer can have a car painted any colour that he wants so long as it is black."

Since nearly a century has passed since this is supposed to have happened, it's easy to take the story at face value. One common explanation for it is that black paint was the quickest to dry after it had been sprayed on to the car. Having read this far, you may suspect that things are not what they seem. And you would be right.

Slide of

Slide of

Model T Ford: the truth

Ford claimed that he made his announcement in 1909. This is unlikely, partly because the Model T went into production in 1908, and partly because black wasn't available at all for the first six years. According to a comprehensive study by Model T historian Dr Trent Boggess, all the cars built between late 1914 and the summer of 1925 (approximately 11.5 million of the over 15 million produced) were indeed black. Other colours were reintroduced for the final years of production.

Applying and drying the various layers of black took about four days. Spray painting had nothing to do with it, because Ford did not use that method until 1926. To sum up, it's true that most Model Ts were black, but untrue that all of them were.

Slide of

Slide of

Most boring Grand Prix: the myth

Although there are several contenders, the 2005 United States GP at Indianapolis is often referred to as the most boring Grand Prix race ever held (not counting the 2021 Belgian GP, since two laps behind a safety car hardly counts as a race at all). The Michelin tyres fitted to 14 of the cars entered were found to be at risk of a blowout on the banked Turn 13. All sensible methods of resolving this were dismissed, so those cars came into the pits for good at the end of the warm-up lap. The spectators, who had not been informed of any of this, understandably became rather cross.

Only six cars remained, all running on Bridgestone tyres. Two Ferraris finished a lap ahead of two Jordans, which were in turn a lap ahead of two Minardis. What could be more boring than that?

Slide of

Slide of

Most boring Grand Prix: the truth (or at least a valid opinion)

Here's what could be more boring than the 2005 United States GP: the 1926 French GP. Twelve cars were entered, but only three Bugattis turned up. Pierre Vizcaya (1894-1933) retired early on with piston failure. Bartolomeo Costantini (1889-1941), fearing the same would happen to him, slowed down to such an extent that he finished 15 laps behind winner Jules Goux (1885-1965) and was not classified.

By comparison, the race at Indianapolis 79 years later was positively fraught with excitement.

Slide of

Slide of

Silver Arrows: the myth

Silver Arrows is the collective name for the Mercedes cars driven in the F1 World Championship by Lewis Hamilton (born 1985), Nico Rosberg (born 1985), Valtteri Bottas (born 1989) and on one occasion George Russell (born 1998).

Mercedes has won both the Drivers' and Constructors' titles in the Championship every year from 2014 to 2020. The name has fallen slightly into disuse recently, because the paintwork was changed from silver to black at the start of the 2020 season as a statement against discrimination. All of the above is true, but it becomes mythical if anyone claims that it is the whole truth. The story of the Silver Arrows is in fact much longer.

Slide of

Slide of

Silver Arrows: the truth

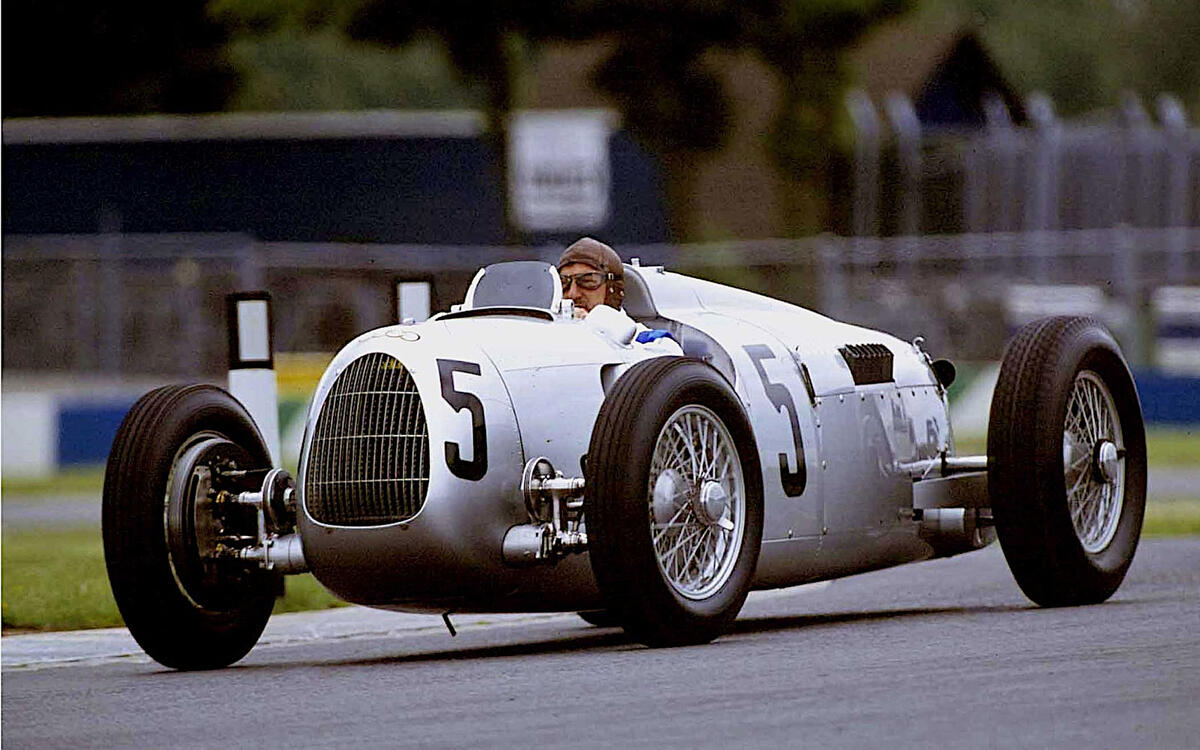

The first Silver Arrows were the formidably powerful Auto Union (pictured) and Mercedes cars which almost completely dominated Grand Prix racing from 1934 to 1939, and also set a number of speed records. The name resurfaced in the mid 1950s, when Mercedes produced the extraordinary W196 F1 car. This time, the company remained in the sport just long enough for Juan Manuel Fangio (1911-1995) to secure two of his five World Championship titles.

Today's Grand Prix Mercedes are therefore at least the third batch of cars to be known as Silver Arrows, even if you don't include the times when the term was used in sports car racing.

Slide of

Slide of

Vauxhall Nova: the myth

The Vauxhall Nova, it is often said, could not be sold in Spain because its name sounded like no va, the Spanish phrase meaning "it doesn't go". We dealt with this nonsense when talking about the Chevrolet Nova. To recap, it isn't true because no va and nova (meaning “nova”) sound different in Spanish.

In the case of the Vauxhall, though, there's an extra element of fiction which deserves to be thrown into the sea.

Slide of

Slide of

Vauxhall Nova: the truth

GM Europe's policy at the time (though it later changed) was for its vehicles to be called ‘Opel something’ in all markets except the UK, where they would be badged as Vauxhalls and given a different model name.

The little hatchback was sold in all left-hand drive markets, and in Ireland, as the Opel Corsa but was renamed Vauxhall Nova for the UK. In other words, it was never going to be called Nova in Spain in the first place, so there was no reason to change the name, and there would have been no problem even if it had been changed. End of story.

Slide of

Slide of

Toyota Corolla: the myth

The Toyota Corolla is sometimes referred to as the world's best-selling car. On the face of it, it's not even close. Toyota reported in August 2021 that Corolla sales had exceeded 50 million units. That monster figure is at least ten million more than the combined total for two previous record holders, the Volkswagen Beetle and the Model T Ford.

But it all depends on how you look at this. And if you look at it correctly, the story becomes very different.

Slide of

Slide of

Toyota Corolla: the truth

There's no reason to doubt Toyota's claim as it stands, but how do you define what a Corolla actually is? It definitely isn't a single model. Corollas have been built since 1966 over 12 model generations. The earliest and latest bear no resemblance to each other, apart from their names.

By contrast, the Model T and the Beetle were developed very slowly throughout their production lives. That's not to say that parts could be swapped between examples built decades apart (at least in the case of the VW) but it would be fair to speak of them both as being individual models. Not so with the Corolla. However, Corolla is beyond dispute the world's best-selling automotive nameplate. That's something worth celebrating, even if it's not the same as being the best-selling car.

Slide of

Slide of

V12 engines: the myth

What, in a motoring context, could be more Italian than the V12 engine? Surely our Latin friends have this one wrapped up? Ferrari is perhaps the most famous manufacturer of V12s, but Alfa Romeo, Fiat, Lamborghini and Maserati have built them too.

That's a high proportion of the Italian motor industry, but - as you may have suspected by now - there's more to it than that.

Slide of

Slide of

V12 engines: the truth

In fact, the V12 is not specifically Italian at all. To say that Auburn, BMW, Cadillac, Jaguar (E-Type pictured), Mercedes, Pierce-Arrow and Toyota have also built V12 engines is merely to scratch the surface. The Italians didn't even get there first. The first ever V12 was a powerboat engine built in London by the Putney Motor Works in 1904. Carburettor manufacturer, farmer and violin maker George Schebler (1865-1942), clearly a man good with his hands, built a one-off V12 car - with cylinder deactivation! - four years later.

The V12-powered Packard Twin Six went into production in 1915. For reference, Ferrari's first V12 did not appear until 1947.

Slide of

Slide of

Volkswagen Beetle: the myth

Volkswagen's first model was also its longest-lived, most-loved and best-selling to date. Conceived by Adolf Hitler to provide transport for ordinary Germans in the 1930s, it went into full production after World War II, developed an enormous fan base and was still being built in Mexico as late as 2003.

In 1999, it was voted fourth in the Car of the Century competition, behind the Model T Ford, Mini and Citroen DS but ahead of the Porsche 911. Its name, of course, was Beetle. Everyone knows that. Don't they?

Slide of

Slide of

Volkswagen Beetle: the truth

In fact, the official name for the car was Type 1. Model names, including 1200, 1302 and 1500, referred, more or less, to the size of the engine. Early on, Germans began to call it the Käfer, meaning “beetle”, on account of its shape. The name was adopted by English speakers, who also called it the Bug.

Volkswagen did not use the Beetle name until 1997, and that was for the second-generation, front-wheel drive model which had no connection with the original car other than a vaguely similar appearance.

Slide of

Slide of

Women in motorsport: the myth

Motorsport is often said - even, on occasions, by women - to be a man's game. It's true that no woman has driven in a World Championship F1 race since Lella Lombardi (1941-1992, pictured) finished 12th in the 1976 Austrian Grand Prix. Female winners of international championships are also rare.

But hold on a minute. Is this because women are less good at competitive driving, or is it a question of arithmetic?

Slide of

Slide of

Women in motorsport: the truth

At present, 20 drivers compete in the F1 World Championship, and they are all male. This is to be expected if fewer than five percent of all drivers of single-seat racing cars are women, which is almost certainly true (though the proportion is much higher than it used to be). Beyond five percent, it becomes more likely that there will be a female F1 driver.

Similar discrepancies occur in other forms of motorsport. It's about numbers, not ability. Anyone who thinks otherwise might want to take a look at the following list of outstandingly talented women who have demonstrated, over more than a century, that driving talent has nothing to do with chromosomes. And there are many, many others:

Joan Newton Cuneo (1876-1934), racing and record breaking

Brittany Force (born 1986, pictured), drag racing

Elizabeth Junek (1900-1994), racing

Jutta Kleinschmidt (born 1962), rally raids

Michele Mouton (born 1951), rallying

Shirley Muldowney (born 1940), drag racing

Lorraine Peck (1958-1975), karting

Kay Petre (1903-1994), racing

A close look at some of the most mistaken beliefs in the world of cars

Advertisement