Slide of

Slide of

For embarrassing, grand-scale corporate catastrophes there was once only one word: Edsel.

Over 60 years ago, Ford spent $250 million - perhaps $2.5 billion in today’s money - on the launch of a new brand whose chief impact was to become known as one of the worst product launches of all time. The tale behind it became a case study for the corporate world and the name became a synonym for failure.

This is the story of how it was born, how it died on November 19th 1959, and how its failure ironically laid the foundation stone for one of Ford’s most remarkable successes…

Slide of

Slide of

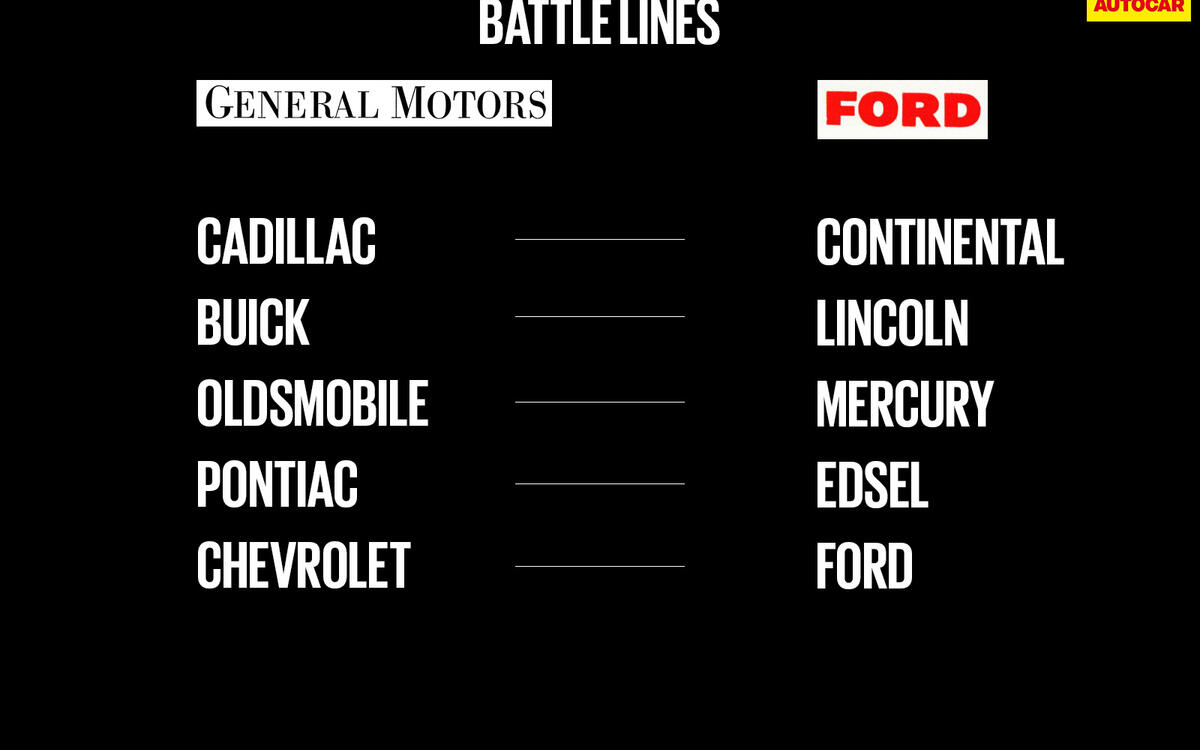

Fighting the General

Despite its ultimate failure, the thinking behind the Edsel division was sound. Back in the mid ‘50s Ford had three brands – Ford itself, Mercury and Lincoln – whereas General Motors had five, its mid-range Oldsmobile, Pontiac and Buick marques flanked by affordable Chevrolet and prestigious Cadillac.

Against this trio Ford could only muster Mercury, but neither this nor upscale Lincoln were profitable, in stark contrast to GM’s money-making armoury of marques. The problem was hardly new. Ford had been grappling with it since the 1920s, with the rise of the multi-brand General Motors. Why it took three decades to mount a full-scale riposte is a story worthy of Netflix. Jealousy, intransigence, hubris and empire-building produced paralysis, poor decisions, few winners and many losers.

Slide of

Slide of

The legacy - Henry Ford, and Ford Model T

This is the car that democratised motoring, pictured with its creator. Outsold only by the VW Beetle, it made Henry Ford (1863-1947) richer than some countries. But he would later refuse to change his ways, or the car that had propelled him there. By 1927, Ford’s US market share had plunged to 19% from 48% in 1922. The Model T was old, and newly affluent buyers were trading up.

Slide of

Slide of

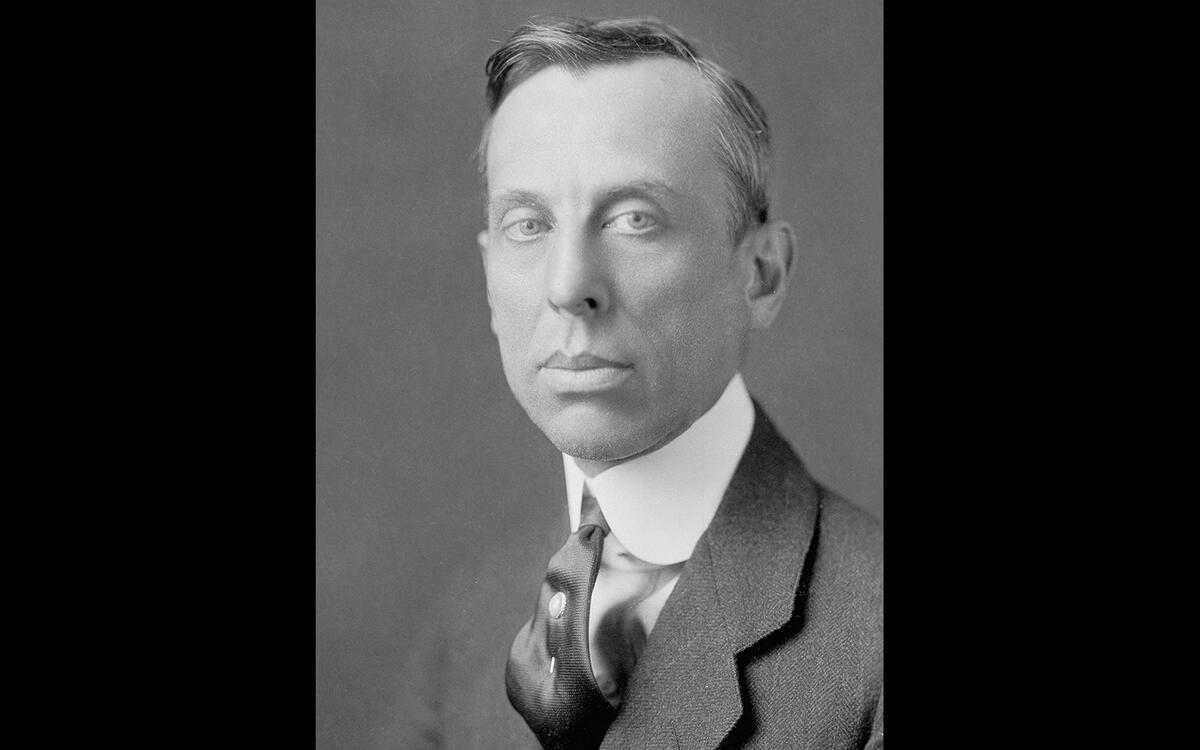

GM’s Alfred P Sloan, and cars for every purse and purpose

Alfred P Sloan (1875-1966) is a major reason why we car buyers have enjoyed so much choice for so long. He was the architect behind the revival of 1920s General Motors and its mish-mash of money-losing brands accumulated by its co-founder, the fairy-tale charming, corporate shopaholic that was William C. Durant (1861-1947).

Sloan arranged brands and models hierarchically to produce “a car for every purse and purpose,” his industrial enabler the canny sharing of bodies across brands, each flaunting a distinctive, add-on décor.

Slide of

Slide of

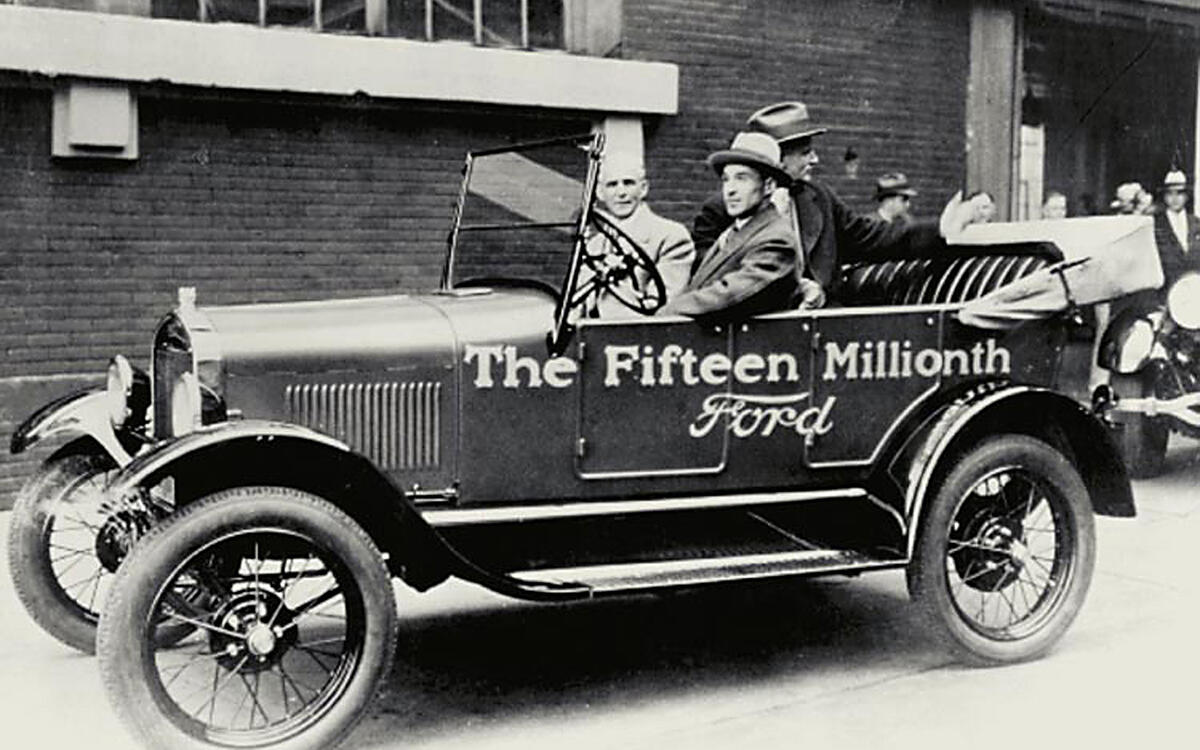

The Quiet Persuader

It was Henry Ford’s son Edsel Ford (1893-1943, pictured driving here) who finally convinced his father (alongside him) to replace the Model T – so abruptly, that there was a gap between the T’s demise and the Model A’s introduction. He also persuaded his father to buy struggling luxury marque Lincoln, which Edsel successfully revived.

Slide of

Slide of

Ford’s first response - 1936 Lincoln-Zephyr

The streamlined, art deco V12 Lincoln-Zephyr was Ford’s first medium-priced model. Conceived by Edsel Ford, it sold well enough to rescue Lincoln, despite being too pricey to win a big chunk of the segment.

Relatively crude suspension and outmoded mechanical brakes were a disappointing contrast to its bold design, but despite the V12’s troubled reliability it was a success.

Slide of

Slide of

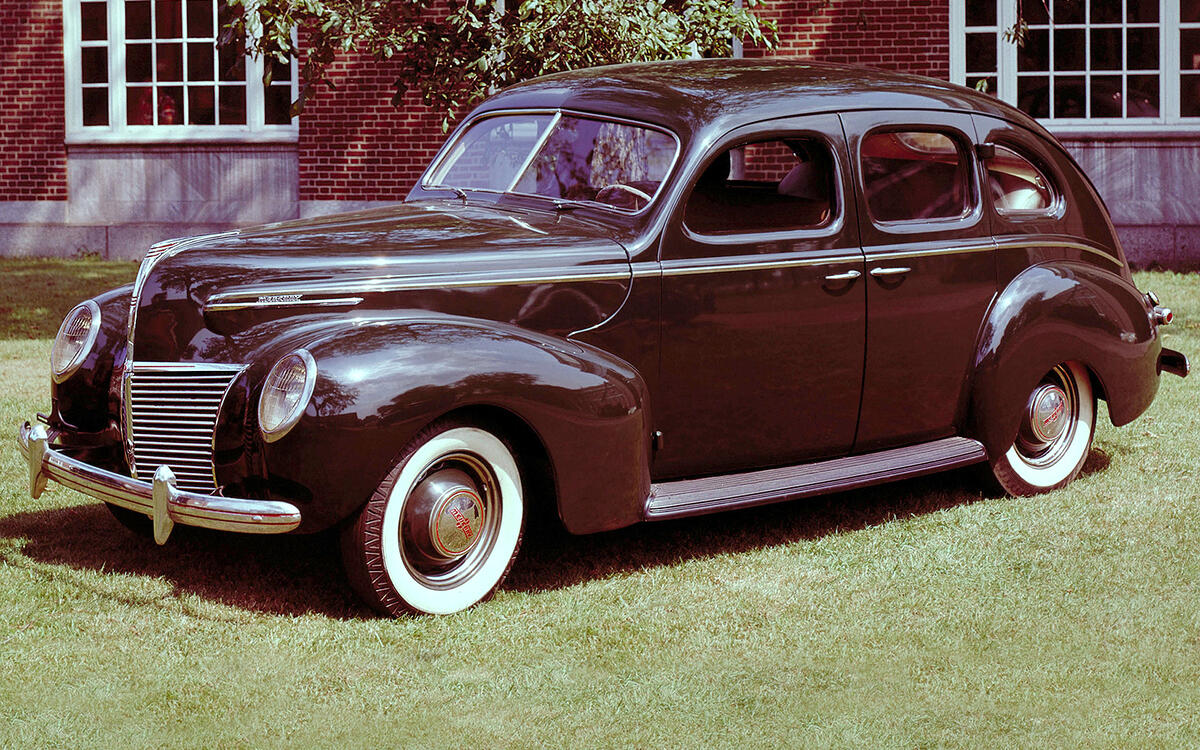

And the second - 1939 Mercury-Ford

Edsel’s second mid-market shot was with new badge Mercury. Initially he insisted on appending the Ford name to it, somewhat undermining the move upscale. “Ford” was soon dropped, however, and Mercury got off to a good start before World War Two.

Despite these successes, Edsel’s father gave his only son a hard time. Stomach cancer killed him in 1943, aged just 49.

Slide of

Slide of

Chasing GM

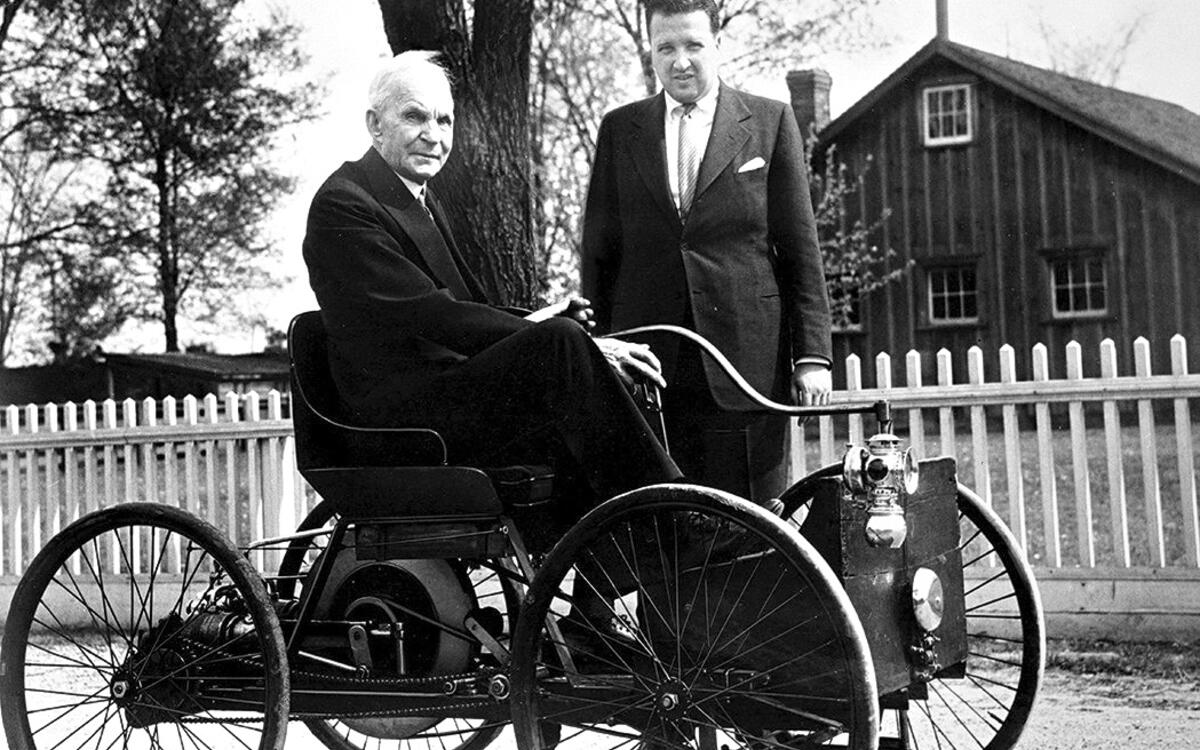

With Edsel gone and Henry Ford retired, Edsel’s 28 year old son Henry Ford II (1917-1987, pictured right with grandpa) became CEO in 1945 of a company short of structure, new products and executives to lead it, his grandfather’s sometimes paranoid, often brutal reign gutting the business of senior management.

By the end of WW2, Ford had almost no corporate plan, its engineering, finance and design departments barely existed and its plants were in disarray, its munitions orders having swiftly ceased with the arrival of peace. Ford swiftly poached GM’s Ernest R Breech (1897-1978), the man groomed to succeed Sloan, and set about copying GM’s organisational structure.

Slide of

Slide of

The Whiz Kids and Turf Wars

Henry Ford II also hired a group of former US Army Air Force officers. Business-school graduates, they were cost-control and statistical analysis advisers – expertise conspicuously absent in a company that weighed bundles of invoices to estimate their value.

Quickly named The Whiz Kids, they soon made the finance department their power base, setting the scene for a corporate turf war that would bear heavily on the Edsel brand. One of the most famous Kids, Robert McNamara, is pictured here at far right.

Slide of

Slide of

The Art of Profitable Costing

Ford was baffled at how GM managed to make money from lower volume models, even if they were priced higher. It was even more baffled when it belatedly learned the art of costing cars, discovering for the first time how much money Lincoln and Mercury had been losing.

The secret lay in using three body sizes across all its brands, their similarities cleverly disguised with chrome, colour and if necessary, a few model-specific panels, as GM usefully illustrated in this 1957 advertisement. This realisation added rocket fuel to the Edsel project.

Slide of

Slide of

The Grand Plan’s Planners

The task of devising a product plan for the new E-car (for Experimental – the Edsel name was yet to come) fell to product planning boss Lewis Crusoe (1895-1973, pictured) and Whiz Kid Jack Reith. Crusoe was the father of the Thunderbird, while Reith was fresh from turning around Ford’s troubled French division.

They produced a far-reaching strategy not only for the new E-Car but also Lincoln and Mercury, to target Buick, Oldsmobile and Pontiac.

Slide of

Slide of

The Grand Plan

The Crusoe-Reith plan was highly ambitious. Three core bodies were planned for Ford, Edsel, Mercury and Lincoln, topped off with new ultra-luxury brand Continental.

The plan was less costly than it sounds, with some of the bodies already under development, and it would give Ford five brands, Edsel to slot between Ford and Mercury, now moved upscale, matching GM’s ‘big five’.

Slide of

Slide of

Network Gains

Despite the strategy’s risky ambition, Ford’s board was primarily attracted by its dealer network plans. Ford and Mercury had 8000 US dealers in 1955, GM 16,500 and Chrysler 10,000.

Crusoe and Reith figured that adding an exclusive Edsel network would rapidly boost this to 10,600 dealers. Sales boss Jack Davis however worried that moving Mercury upmarket to make way for the new brand might lose customers unwilling to pay more. The all-new, untested dealer network he also considered a risk; he wanted a more measured growth. Nonetheless, on April 15 1955, the ‘E-car’ plan was born.

Slide of

Slide of

“The conception of an entirely new vehicle”

That was the near-impossible brief for young design chief Roy Brown (1916-2013). Impossible, because Ford’s newly adopted interchangeability mission meant using an existing body, the only original elements allowed being the nose and tail, bumpers, rear door lower panel, the bonnet and boot lid, ornamentation and the grille.

Despite these limitations, the objectives required that “aesthetic uniqueness shall be considered essential.” Brown notably rejected the tailfins that were then all the rage, replacing them with boomerang rear-lights that even today look modern. On the fins he was ahead of the curve, as they would be gone from US cars within a few years. “I hated the blasted fins on the Cadillac,” he later said. “They were dangerous, too.”

Slide of

Slide of

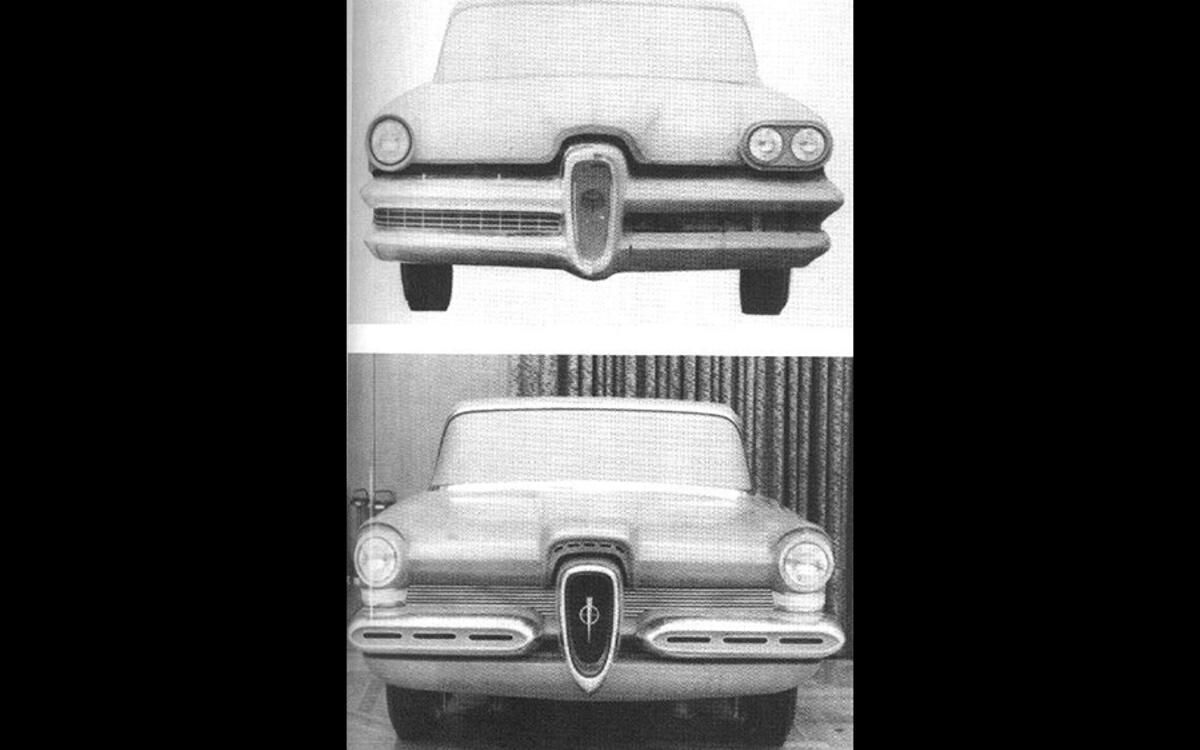

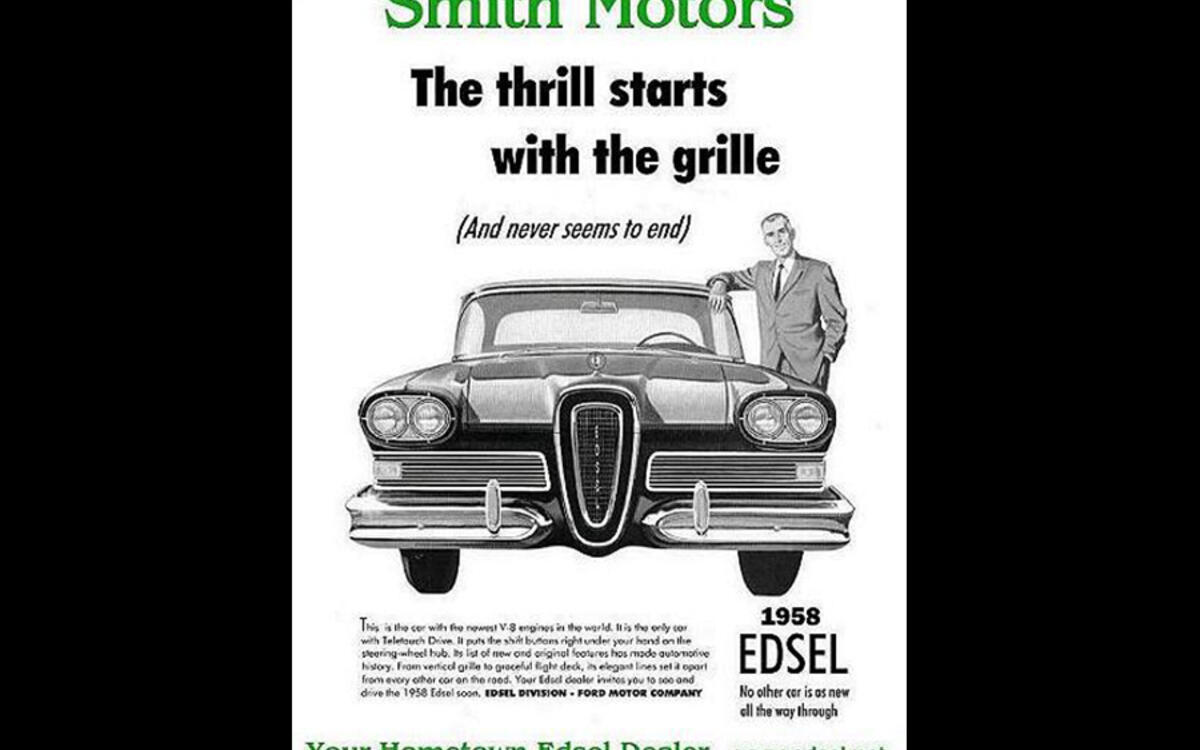

That Vertical Grille

The start point for Brown and his team was to plaster the studio walls with images of existing cars. They soon noticed that the grilles of most current US models were horizontal, but some high-end European models, among them Rolls-Royce, Mercedes-Benz and Jaguar, had vertical air intakes.

So Brown worked on a vertical approach for Edsel, virtually guaranteeing a stand-out look among its domestic rivals.

Slide of

Slide of

Grille Spill

Early sketches of the Edsel showed plenty of elegant promise, a slender vertical ellipse flanked by counter-weighting quarter-bumpers.

But engineering colleagues demanded a bigger aperture for cooling, the twin-ringed, horse-collar shaped result famously dubbed “an Oldsmobile sucking a lemon”, and the grille would become a cornerstone of the car’s marketing (pictured). But it was controversial and to some eyes, ugly.

Slide of

Slide of

Finding a Name - Any Name

Edsel. It’s not the sexiest of words. Sociologist-turned-Ford-corporate David Wallace (1908-74) was tasked with finding a name for the new brand, hiring agencies and subjecting his colleagues to post-lunch screenings of suggestions. But he was surprised at how little response he got.

Suspicious, he dropped BUICK in as a test, the lack of reaction to this GM name confirming his hunch that most attendees used the screenings for an illicit, post-prandial snooze.

Slide of

Slide of

The poet - Marianne Moore

Wallace also turned to the literary world and US poet Marianne Moore (1887-1972). It was an arrangement that yielded some of the most elegantly phrased correspondence ever seen in the motor industry, later published in The New Yorker. And a string of original but hopelessly inappropriate choices.

Most infamous were Utopian Turtletop, Resilient Bullet, Mongoose Civique, Andante con Moto, Ford Silver Sword and Varsity Stroke. That Moore refused a fee was some compensation.

Slide of

Slide of

Edsel’s Name Taken in Vain

An ever more desperate Ford ploughed on, advertising agency Foote, Cone & Belding (FC&B) collating a staggering 6000 names, complete with word associations, into six bound volumes. They were presented to an astonished Richard E Krafve (pictured left), Edsel general manager (and a former Army colonel), who insisted that FC&B’s two offices hack them back to a mere 10 names.

Amazingly, four names – Citation, Corsair, Pacer and Ranger – appeared on both lists. These were presented to a committee chaired by Ernest Breech, who didn’t like any of them. B list names included, incredibly, Drof - Ford spelt backwards - Benson (a Ford family first name) and Edsel. The man himself would surely have disapproved, and it seems his son certainly did. But despite being CEO, Henry Ford II was persuaded, and Edsel was decided on November 8 1956, and a logo swiftly drawn (right).

Slide of

Slide of

Product Planning Plants a Bomb

Slow sales of Ford’s Thunderbird two-seater (pictured) were to have far-reaching effects on Edsel. The plan was to turn it into a four-seater hardtop, and to switch it from body-on-frame construction to a unibody, Ford lagging the competition with this development.

Building the Thunderbird alone with a monocoque wasn’t viable, so the ’58 Lincolns were switched to a unibody too, which in turn denied Mercury a body-on-frame source for the Super Mercury intended to take the marque upmarket of Edsel. The Mercury and Super Mercury would instead all share the same basic architecture.

Slide of

Slide of

The Press Launch

The three-day Edsel media launch included 250 journalists and unusually, their wives. A stunt-driving display and test drives preceded an evening in a nightclub created in the design center, at which 71 scribblers were presented with Edsels to drive to their local dealers.

One car’s engine seized when its oil-pan fell off, while another scared its driver witless with brake failure.

Slide of

Slide of

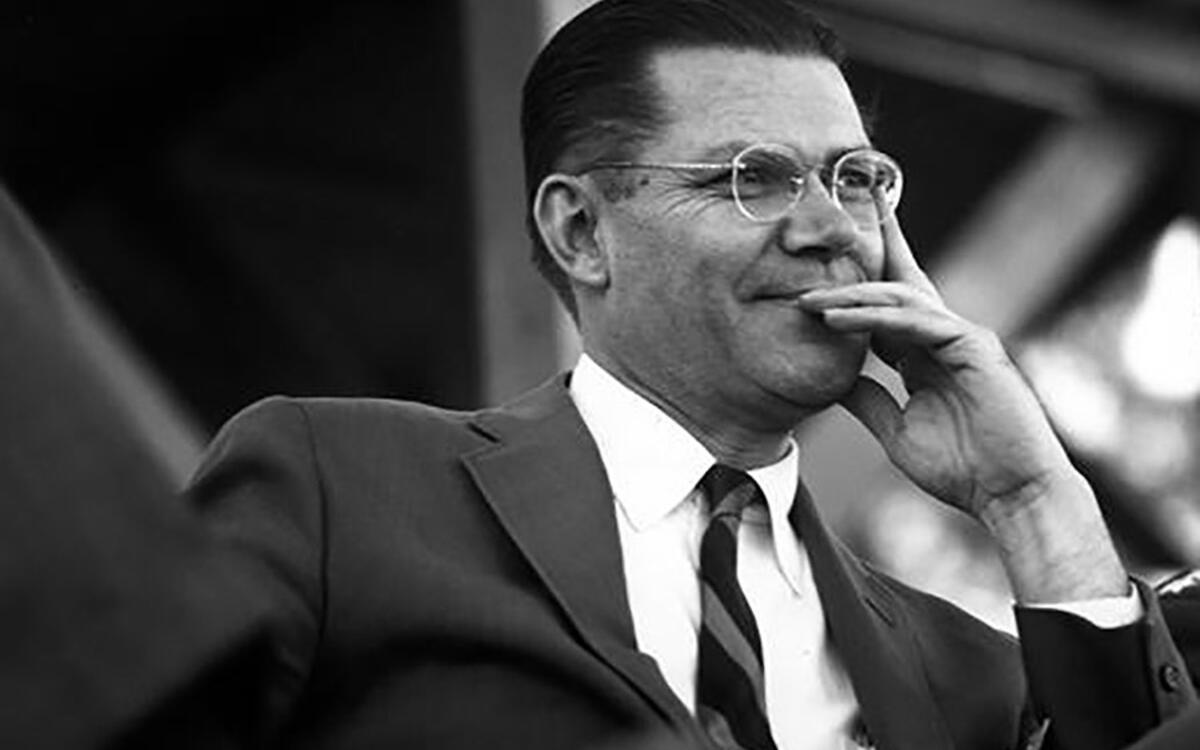

McNamara the Knife

The best-known Whiz Kid was Robert McNamara (1916-2009), who by 1956 had risen fast through the ranks. Hugely ambitious, his austere statistical analyses frequently failed to account for the indulgent whims of buyers excited by gimmicks and the status-enhancing power of the automobile. Sales, profit and control were what motivated this man, his powerful sense of logic struggling to see the sense of medium-priced cars unless they sold, and sold big.

Incredibly, McNamara didn’t even wait for the Edsel to fail, mentioning plans to discontinue the brand to Fairfax Cone (1903-77) of ad agency FC&B on the very evening of Ford’s internal launch party.

Slide of

Slide of

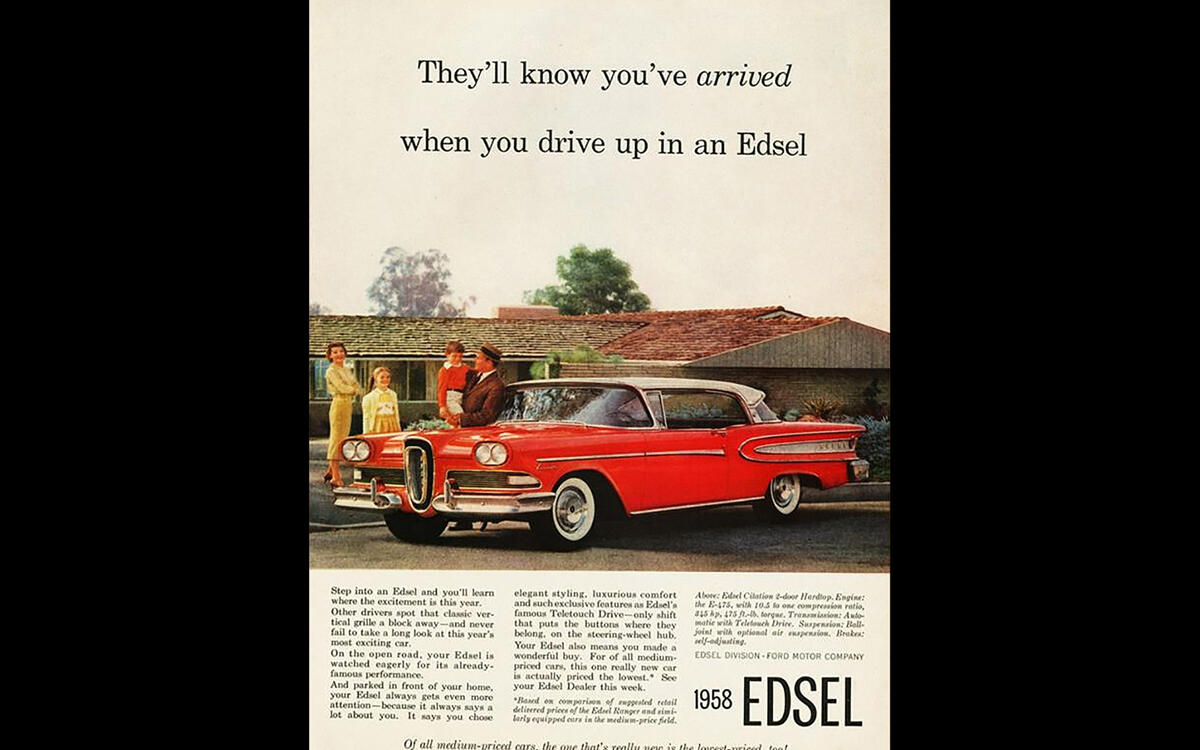

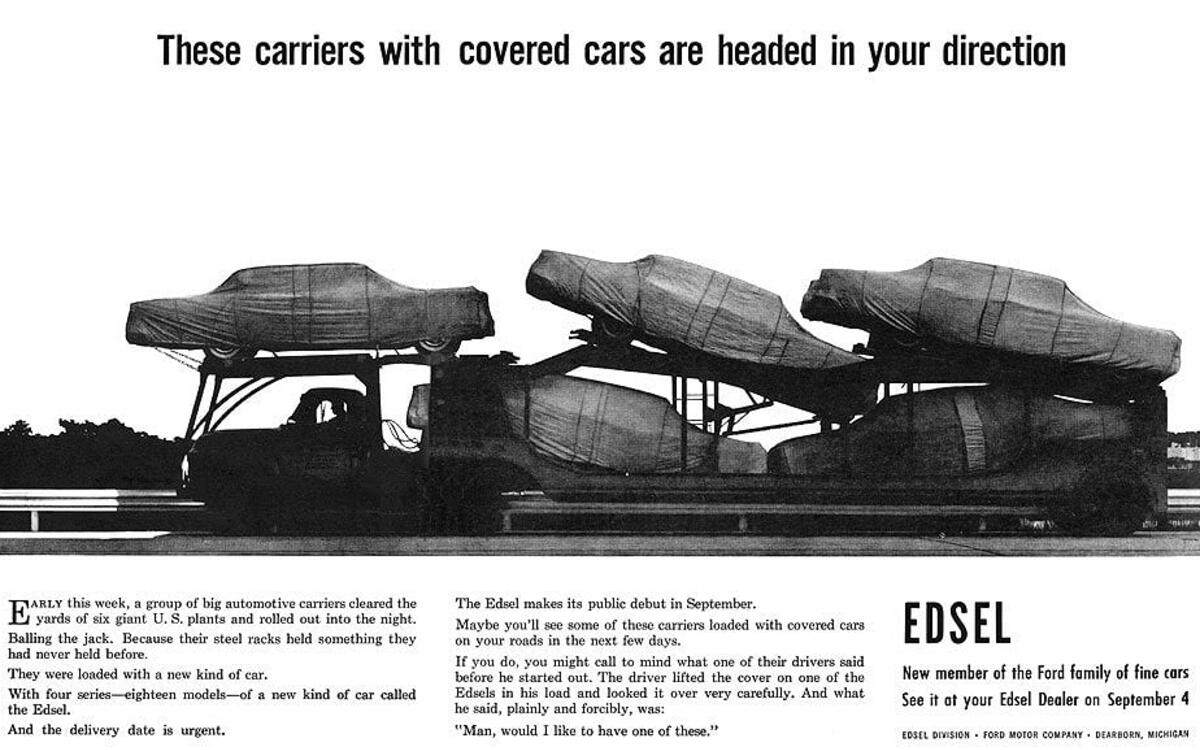

E-Day - 4 September, 1957

On this day – a Wednesday – prompted by a huge marketing campaign (pictured), a staggering 2.85 million Americans visited Edsel dealers. There was plenty to see, if not the wheeled revolution promised by the excitable pre-launch hype.

Slide of

Slide of

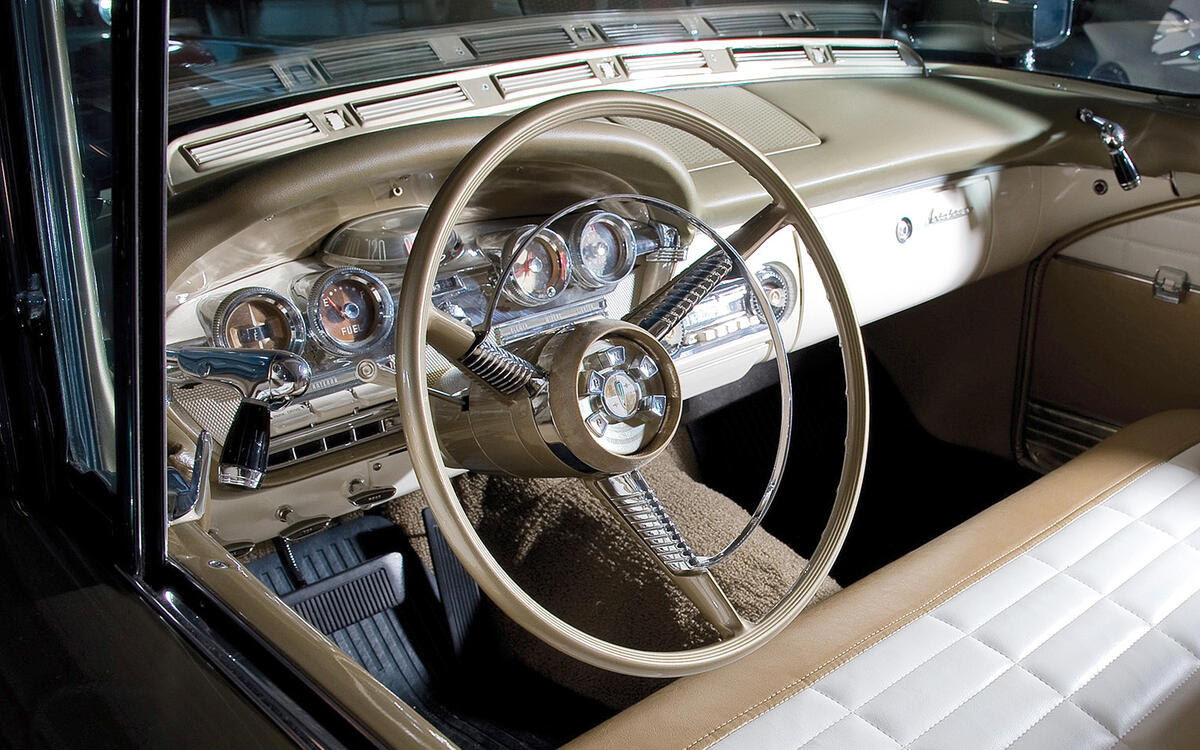

Innovation

Novelties included Teletouch transmission buttons mounted in the steering wheel boss, a revolving drum speedometer that glowed red if you exceeded a pre-determined speed and less visibly, self-adjusting brakes and a three-stage engine cooling system for faster warm-up.

The last of these was well ahead of its time – far enough indeed to cause trouble in service – but the Edsel was no Citroën DS, the 1955 French fancy leaping two decades in one fluid-suspended bound.

Slide of

Slide of

At the wheel

In this photo, Henry Ford II (naturally in the driving seat) can be seen alongside younger brothers Benson Ford (centre) and William ‘Bill’ Clay Ford. Bill Ford was instrumental in ensuring that when Ford went on the stock market in 1956, the family kept 40% of the voting stock rather than the 25% originally planned.

This ensured effective family control of the company, which continues to this day.

Slide of

Slide of

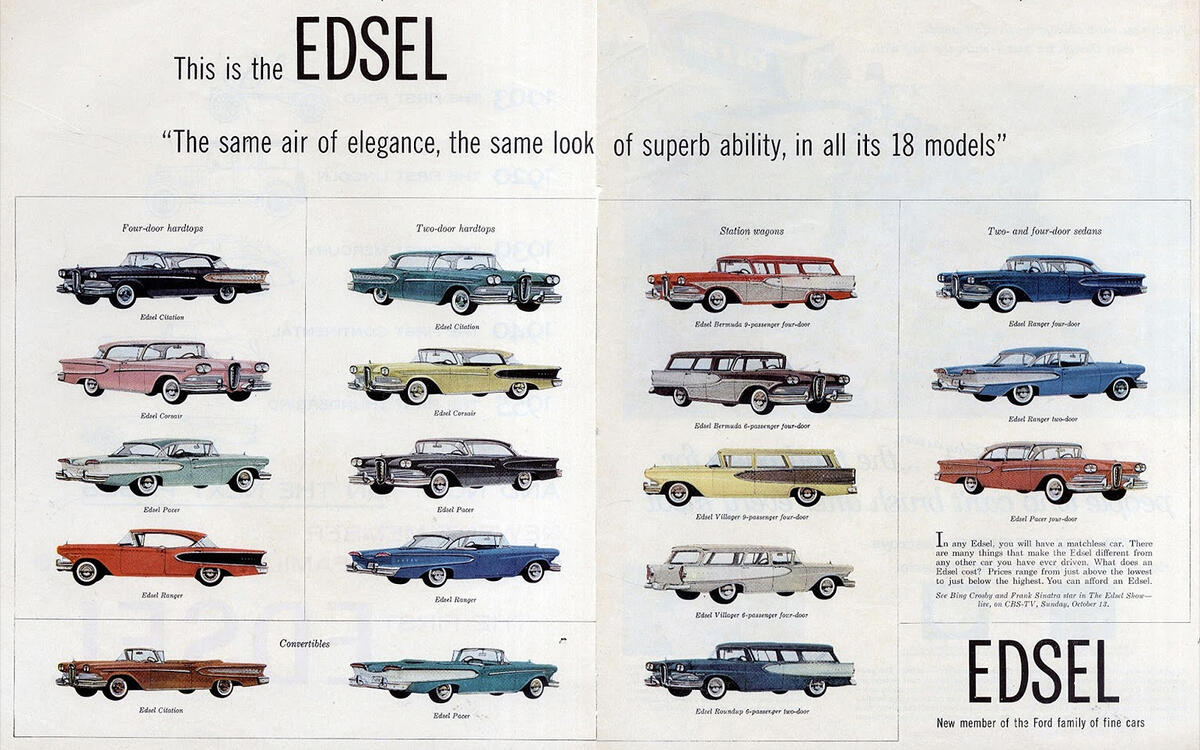

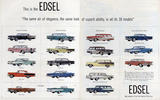

A Vast Range

Had Ford’s factories been able to supply enough Edsels – there were assembly issues, many serious – some of those near-three million Americans would have discovered two basic Edsel sizes from which sprouted no less than 18 varieties of sedan, hardtop, convertible and station wagon arranged into four model families.

Ironically these were badged Pacer, Ranger, Corsair and Citation, names all previously proposed for the Edsel division itself. This – and six Edsel factories – was what Ford’s $250 million of ambition had paid for.

Slide of

Slide of

Sales

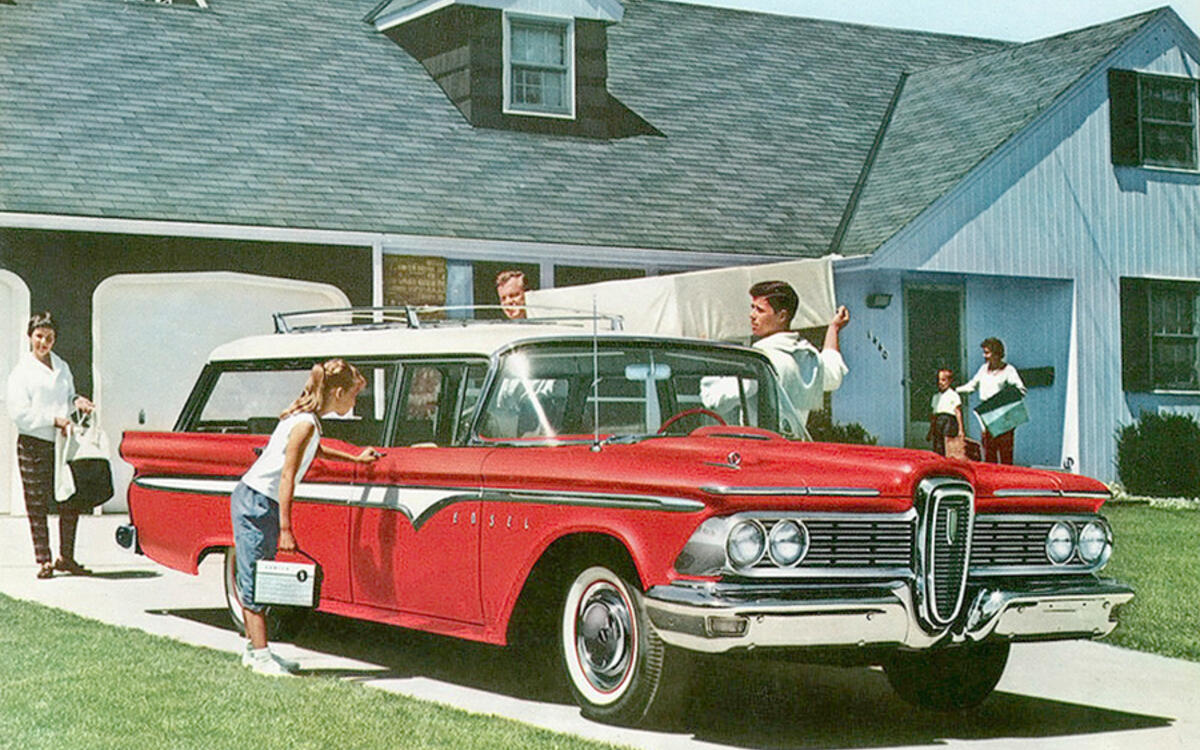

More than 6500 Edsels were delivered on the first day, and another 4095 over the next 10. After that, sales sank. The launch was botched, a costly TV Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra promo on The Ed Sullivan Show failing to restore momentum.

Most serious, though, was that the mid-price segment had shrunk by 40% over the past two years as America’s long post-war boom came to a sputtering halt. By October, sales had fallen to an annual rate of 100,000 cars – half the target.

Slide of

Slide of

The Market Moves

That the market shifted McNamara's way confirmed to him, at least, a reason to kill Edsel. With less money around, suddenly buyers wanted a smaller, more economical model, and many wanted a second car in the household for the first time and had no need for V8-powered vastness; the longest Edsel was 5560mm (219in), and smaller models were hardly compact at 5415mm (213in).

Ironically there was another model, the Edsel B, under development that would have been much closer to what the market suddenly demanded. A compact saloon, it was developed in parallel with the budget Ford Falcon.

But with Edsel’s demise it was reassigned to the Lincoln-Mercury division and initially sold without branding as Comet (pictured). Traces of Edsel could be seen in its taillight and dashboard design. Ironically its 116,331 first-year sales topped Edsel’s three-year total.

Slide of

Slide of

The ‘59s

As was Detroit’s way, there would be a refreshed look for the ’59 Edsels, work starting as soon as the 1958 design was frozen for production in late 1956. The rework was initially ambitious, and included the innovative ergonomic cockpit intended for the original Edsel. But other forces were at play.

McNamara had become head of product planning in September 1957 as the headwinds facing Edsel strengthened. The scope of the ’59 models was scaled back, and early in 1959 Edsel was rolled into a new Mercury-Edsel-Lincoln division (M-E-L) that saw thousands of white-collar Edsel employees dismissed, and the big-bodied versions deleted.

PICTURE: 1959 Edsel Ranger

Slide of

Slide of

Dealers’ Despair

In spite of the disappointing sales the Edsel network of exclusive dealers continued to grow - disastrously, in retrospect - reaching a February 1959 peak of 1568. Some dealers read rumours of the brand’s demise just as they signed on.

James Nance (1900-1984, pictured), M-E-L general manager (and former Packard boss), was very sympathetic to their plight; he received many at his office in tears, their personal fortunes at risk – and many took on Mercury franchises. Nance attempted to keep Edsel alive, but McNamara manoeuvred to have him fired in August 1958. Momentum behind the Edsel rapidly drained away and with it Ford's commitment, despite the hundreds of dealers who had invested so much.

Slide of

Slide of

The Cull

For the 1960 model year the Edsel line-up was pared back to near pointlessness. Only the Ranger remained (a sedan, a hardtop, a convertible, and the Villager wagon, pictured), and it was heavily based on the 1960 Ford. The vertical grille had gone, the car instead distinguished by a split front grille similar to Pontiac’s, the twin vertical taillights more now more memorable than the grille.

The 1960 Edsel was announced on October 15th 1959, and on November 19th 1959 the 2846th ’60 model and last Edsel was produced, taking the total to 110,810 vehicles.

Slide of

Slide of

The Aftermath

Of Ford’s $250m investment around $100m was lost but the rest was spent on factories, and here’s where this tale has a twist. The compact Falcon (launched in 1959) proved a hit, but that was nothing to compared to the two-door it gave birth to: the Mustang, unveiled in April 1964.

Deliberately priced to sell, Ford nonetheless only forecast first year sales of 100,000 Mustangs. Instead on the day a proud Henry Ford II unveiled the car (pictured) it took 22,000 orders alone. It sold 417,000 Mustangs in its first year on sale, making the car the fastest selling in history at that time – and all made possible because of the increased factory capacity added into Michigan and San Jose, California, a few years earlier for Edsel.

Slide of

Slide of

Why did it fail?

You can blame the name, the controversial grille, over-hyped expectations, poor quality and a market-shrinking recession. But all could have been overcome, and the market would have returned, American affluence and thirst for cars still on the upswing in the wider sense, supported by a surging baby-boom population, which increased from 151 million in 1950 to 203 million by 1970.

More serious errors were positioning Edsel in Mercury territory, and creating an exclusive network, denying dealers a body of existing customers. That the Ford brand had also introduced the upmarket models didn’t help. Worst of all, though, was the lack of long-term commitment from a warring management ultimately led by a man who seemed to understand numbers but not the psychology of car buying.

PICTURE: 1959 Edsel Ranger Villager

Slide of

Slide of

The people

Henry Ford II went on running Ford until 1979; he was still the dominant figure in the company until his death in 1987, aged 70. Robert McNamara briefly became president of Ford but was then recruited to become Secretary of Defense for President John F Kennedy, and then under Lyndon B Johnson.

In that role he became embroiled in the direction of another misadventure, this time with more fateful consequences: The Vietnam War. He was later head of the World Bank, where he still had to bear criticisms of his Edsel role. He died in 2009, aged 93.

Edsel designer Roy Brown defended the car to the end, but the debacle led him to Ford of Europe, where he bounced back with the highly successful Cortina. He drove an immaculate grey-and-white 1958 Edsel Pacer almost to his dying day, and strangers would sometimes offer to buy it from him. “Where the hell were you in 1958?” was his magnificent reply. He died in 2013, aged 95.

Slide of

Slide of

Edsel today

Despite its troubled history - or more probably because of it - affection and interest in Edsel remains high to this day. Even ‘non-car’ people born decades after the car have heard some of the story. There are thriving owners clubs, a useful unofficial website at Edsel.com, and for an ‘everyman’ car, a surprising amount of cars are still alive – and a great community of owners who enjoy getting together (previous picture).

Edsel – How many left?

The registry at Edsel.com records 1144 1958 models, 1191 1959s, and 563 1960s as still in existence, a total of 3000 – and the actual number might be quite a bit higher. Fancy joining the Edsel club? Inevitably they are nearly all in the US and Canada. Running examples can be had from $5000 (£6500), while excellent condition convertibles can go for more than $100,000 (£130,000).

The current auction record for Edsel is for predictably one of the rarest variants, the 1960 Ranger Convertible (enclosed). Thought to be only 10 still in existence, one of them sold for $184,000 in 2007, though prices have generally settled down somewhat since then.

Ford's Edsel: The story behind one of the car world’s most infamous misfortunes

Advertisement