Slide of

Slide of

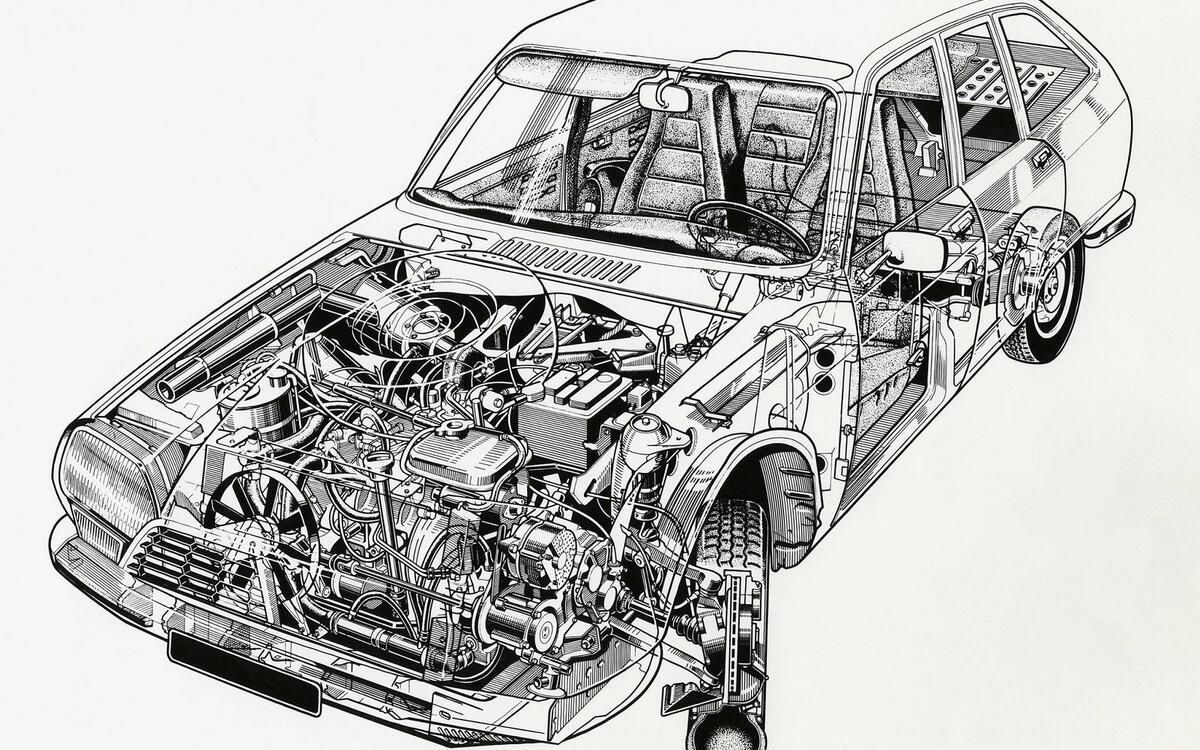

Cars are complex machines, but some take that to a whole new level in the search to break new technological ground.

Sometimes that brings success and other times it results in failure. There are cars that appear to have been more complicated than they ever needed to be just for the sheer design hell of it, like the magnificent homage to over-engineering that was the Mercedes-Benz 600, pictured.

Whatever it is that makes a car more complex than others, here’s our pick of the most finicky designs in chronological order:

Slide of

Slide of

Ford Fairlane 500 Skyliner (1957)

If you want to know what was the first coupé-convertible car, look no further than the Ford Fairlane 500 Skyliner. It was the first car with this roof arrangement to enter series production and went on to sell more than 45,000 examples. The roof itself was the first ever retractable top made up from more than one section and it stowed under the rear deck.

Making this work seamlessly required seven reversible electric motors, four lifting jacks, 10 solenoids, another 10 limit switches and four locking mechanisms. There’s also 607-feet (185m) of wiring to make all of this lot work, so the Skyliner was also the most complex drop-top on the market at its launch.

Slide of

Slide of

Rover P6 (1963)

Rover may have had a slightly staid image up until the 1960s, but that all changed with the P6. Aimed at a new breed of thrusting young executives, it offered superb ride and handling, and excellent safety. Much of this was down to the design of the main structure that left all of the body panels unstressed.

Another unusual P6 feature was the front suspension that used a bell crank design. This gave the car fine comfort and also allowed more width in the engine bay for the proposed gas turbine engine that was ditched and replaced by the famous GM 3.5-litre V8. These design features make the P6 tricky to restore now but also accounted for its popularity in period.

Slide of

Slide of

Mercedes-Benz 600 (1964)

Any car described as a ‘technical tour de force’ is likely to raise eyebrows when it comes to complexity and that’s just what the W100 series of Mercedes 600 did. It came with air suspension, twin heating systems and used vacuum-operation for the powered windows and central locking. On top of that, there was Bosch fuel injection at a time when carburettors were the norm.

From any other car makers, this lot would have sounded alarm bells, but the quality of construction for the W100 was immaculate. Little wonder it was the choice of car for world leaders until its demise in 1981.

However, all of that complexity means the 600 is fiendishly complicated to restore and maintain nowadays, though well cared for examples now command up to £80,000 for the standard saloon model, and rather more for the stretched dictator-spec Pullman model.

Slide of

Slide of

BRM H16 (1966)

Once heard, never forgotten, the BRM H16 was the British racing team’s answer to rule changes for the 1966 Formula 1 season. Famed engine tuners Tony Rudd and Geoff Johnson created the H16 taking two flat-eight motors and stacking them one on top of the other. Each had its own crankshaft and they were geared together.

Lotus fitted the engine to its Type 43, but even the incomparable talent of Jim Clark could only earn a single Grand Prix victory for this motor. It proved to be powerful, but also heavy, unreliable and difficult to work on. The following year, Lotus switch to the new Ford DFV and never looked back.

Slide of

Slide of

Citroën SM (1970)

The SM was the result of Citroën buying Maserati in 1968. Using the Italian firm’s 2.7-litre V6 engine endowed the Citroën with decent performance, but it also had to power the car’s hydro-pneumatic suspension and brakes borrowed from the DS. Along with headlights that turned with the steering and advanced dials, the SM was as advanced as it was fragile.

The fragility meant regular maintenance was vital to keep the Maserati V6 engine ticking as it should and Citroën’s suspension working. Even so, the SM earned a reputation for being fearsomely difficult to keep running correctly and it’s only now the car is really appreciated as the clever machine it is.

Slide of

Slide of

Citroën Birotor (1973)

Citroën more than dabbled with the notion of rotary power for its cars, but ultimately it decided against this design after experimenting with the Birotor. It used a Comotor 624 twin rotor engine as seen in the NSU Ro80 and it turned the GS base vehicle into a fast, refined cruiser. Citroën tested the car with 847 built and supplied to the public.

However, when Peugeot bought Citroën, the Birotor project was scrapped and most of the cars suffered the same fate when Peugeot bought them back. It felt the engine’s complex and unreliable nature would damage the Citroën brand, so the few surviving Birotors offer an enticing glimpse of how Citroën might have developed if it had remained independent.

Slide of

Slide of

Aston Martin Lagonda (1976)

Aston Martin embraced all that was cutting edge for in-car tech when it launched the Lagonda in 1976 at a heady £24,570 – at a time when the average house in UK at the time cost £13,000. It bristled with touch-sensitive panels in place of buttons and digital displays rather than analogue clocks in a cabin that was as angular as the exterior.

It was just what very wealthy buyers wanted, but they weren’t so keen on the reliability of these gadgets that had a habit of failing and were hugely expensive to put right due to their complexity.

Aston Martin simplified the Lagonda’s interior for later models, though it still retained its digi-dash. By then, sales had dwindled to a trickle and Aston sold a total of 645 of these wedge-profiled saloons all the way up to 1990.

Slide of

Slide of

Buick Reatta (1988)

The Reatta was a bold attempt by General Motors to inject some chic into the Buick brand with a sporty two-door, two-seat coupe. It looked the part and should have been a success, helped by its Electronic Control Center touchscreen computer and digital dash display. However, production was over-complicated as it was hand-built in the dedicated Reatta Craft Center rather than on a normal production line.

GM even sent staff to the UK to see how small car companies such as Rolls-Royce made their vehicles. None of this added to the finished Reatta’s appeal to buyers nor its dynamic abilities. It certainly wasn’t a bad car, but the 3.8-litre V6 engine driving the front wheels was short on power and refinement to undermine the Buick’s positioning as a halo sports model. In the end, only 21,751 Reattas were built over four years.

Slide of

Slide of

Mitsubishi 3000GT (1990)

Reel off a spec sheet that includes all-wheel drive, electronically-controlled suspension, active aerodynamics and four-wheel steering, and you’d think the Mitsubishi 3000GT had been launched today. However, this coupé arrived in 1990 and Mitsubishi threw everything at it to make it competitive against the likes of the Porsche 944 and Toyota Supra.

Even the engine was advanced for the period as it was a twin-turbo, quad cam 3.0-litre V6 with 300bhp. This gave fine performance, but all of the techno-wizardry for the aero and suspension couldn’t overcome the dull feel of the dynamics. However, its complexity is now one of the 3000GT’s major draws for those seeking a modern classic coupe.

Slide of

Slide of

Subaru SVX (1991)

After the sales flop of its XT coupé, Subaru persevered with its two-door ambitions with the SVX. It was a determined effort to move further upmarket into territory occupied by the likes of the Nissan 300ZX and Toyota Supra. To do this, Subaru deployed a 3.3-litre flat-six engine and all-wheel drive to make the most of its 230bhp.

Even so, buyers were wary of this mechanical package and other SVX details such as the window within a window side glass. All of this combined with the high ticket price at launch to render the SVX a rarity that was quickly forgotten when the Impreza Turbo turned up and dominated rallying.

Slide of

Slide of

Jaguar XJ220 (1992)

The differences between the concept and reality of the Jaguar XJ220 have been well documented and it all comes down to complexity. Where the original show car had a dry sump V12 engine and four-wheel drive, the reality of building a mid-engined supercar with power to all four wheels was not something Jaguar had an experience of.

The V12 also proved to be physically too big for a road car even though it had been used in Jaguar race cars. To solve this, a much modified version of the MG Metro’s V6 was eventually used in the production versions of the XJ220, which also proved to be complicated cars to work on and maintain despite being far simpler than the concept.

Slide of

Slide of

Porsche 911 Targa (1996)

The Targa has always been something of a halfway house in the Porsche 911 range, offering fresh air driving without the full cabriolet roof. While early Targas had a simple lift-out roof panel, later models moved to a sliding glass panel first seen on the 993 generation in 1996. More like a giant sunroof, this slid back to sit under the rear screen, which hindered rear vision for the driver.

The pop-up glass wind deflector of the 993 was a neat Targa feature, but this was dropped for a more traditional fabric item on the 996. Like the 993, the later 996 Targa was based on the Cabriolet bodyshell and many owners complained of creaks as the Targa roof arrangement was not as stiff as the coupé’s.

For the 991, Porsche came up with an equally complex solution that stowed the roof panel under the rear deck in a similar fashion to the Cabriolet model.

Slide of

Slide of

Peugeot 206 CC (2000)

The Mercedes SLK made the idea of the CC roof attractive, but it was the Peugeot 206 CC of 2000 that brought it to the masses. From £14,530, you could enjoy the comfort and quiet of a coupé or, at the touch of a button, revel in fresh air driving. No wonder the 206 CC went on to sell 360,000 during its lifetime.

However, this versatility came with a caveat and that was the complexity of the roof mechanism. Built by Heuliez for Peugeot, the roof quickly gained a reputation for not folding away completely under the rear deck due to faulty latches. Micro switches could also go on the blink and prevent the roof from raising or lowering. With the roof up, it had a habit of leaking rain in.

Slide of

Slide of

Volkswagen Phaeton (2002)

Volkswagen set itself an ambitious target for the Phaeton luxury saloon. It had to be capable of driving at a sustained 186mph in an ambient temperature of 50-degree Centigrade while maintaining a cool cabin. That’s a tall order, but the Phaeton achieved it thanks to a 6.0-litre W12 engine that was soon to be seen in the Bentley Continental GT.

As well as the motor, the Phaeton came with adjustable suspension, paddle shifters for the automatic gearbox and a centre console infotainment screen long before they were commonplace. This put the car light years ahead of the competition for its advanced tech, but buyers weren’t swayed and instead steered clear of luxury saloon with a ‘VW’ badge in favour of the usual premium brands.

Slide of

Slide of

Citroen C3 Pluriel (2003)

The idea of a coupé-cabriolet was well established by the time the Citroën C3 Pluriel tried to reinvent the concept. Why stick with a mere folding roof when you could remove it completely to create a full four-seat convertible or even a pick-up? That’s what the Pluriel offered thanks to its removeable roof rails.

This is also where the Pluriel’s problems set in. First off, removing those rails required a bit of might to lift them clear or reinstall them. Secondly, there was nowhere inside the car to keep them, so when it started to rain when you were out and about, you got wet.

Then there were build quality issues that made themselves known as rattles and leaks, which simply underlined the C3 Pluriel was an over-complex answer to a question that hadn’t been asked.

Slide of

Slide of

Bugatti Veyron (2005)

It’s hardly a surprise to learn the Bugatti Veyron is a hugely complex machine when its sole purpose what to hit a 253mph top speed. To do that, it used an 8.0-litre W16 engine with four turbochargers to produce as much as 1184bhp. It also came with a seven-speed dual-clutch gearbox, four-wheel drive and rear spoiler that doubled as an air brake.

As if all of that lot wasn’t enough to give Bugatti’s engineers some head scratching, the vast amount of heat generated required a forest of radiators and coolers. As a result, there were three radiators for the engine alone, plus others for the transmission and differential oil coolers and another for the engine oil. Little wonder a routine service rings the till at £14,000 (US$18,200).

Slide of

Slide of

Lexus LFA (2010)

The LFA was a wonderful rare moment of exuberance from Lexus and gifted the world one of the most exciting cars ever made. At its carbonfibre core was a 4.8-litre naturally-aspirated V10 producing 553bhp that was developed with help from Yamaha. This motor could rev so quickly that Lexus deemed a digital rev counter necessary as an analogue version couldn’t keep up with the motor.

Always intended as a halo car rather than a long-term production model, only 500 were made and Toyota stated the LFA was built to act as a reference for future sports models for the next 25 years. That explains details like the radiators mounted behind the rear wheels and turbine design of the wheels to draw hot air away from the brakes.

Ever been confused by what's sitting in your engine bay? Wait 'till you see these complex machines

Advertisement