There is no consensus as to what a supercar even is, let alone when the first one appeared.

Recently, I found the term in a test of a V12 Lagonda printed in a 1938 issue of The Autocar, but some reckon it’s older even than that. Others, however, claim that its use in the sense we understand today is far more recent, becoming part of common speech only in the 1970s and referring only to cars built from the mid-1960s.

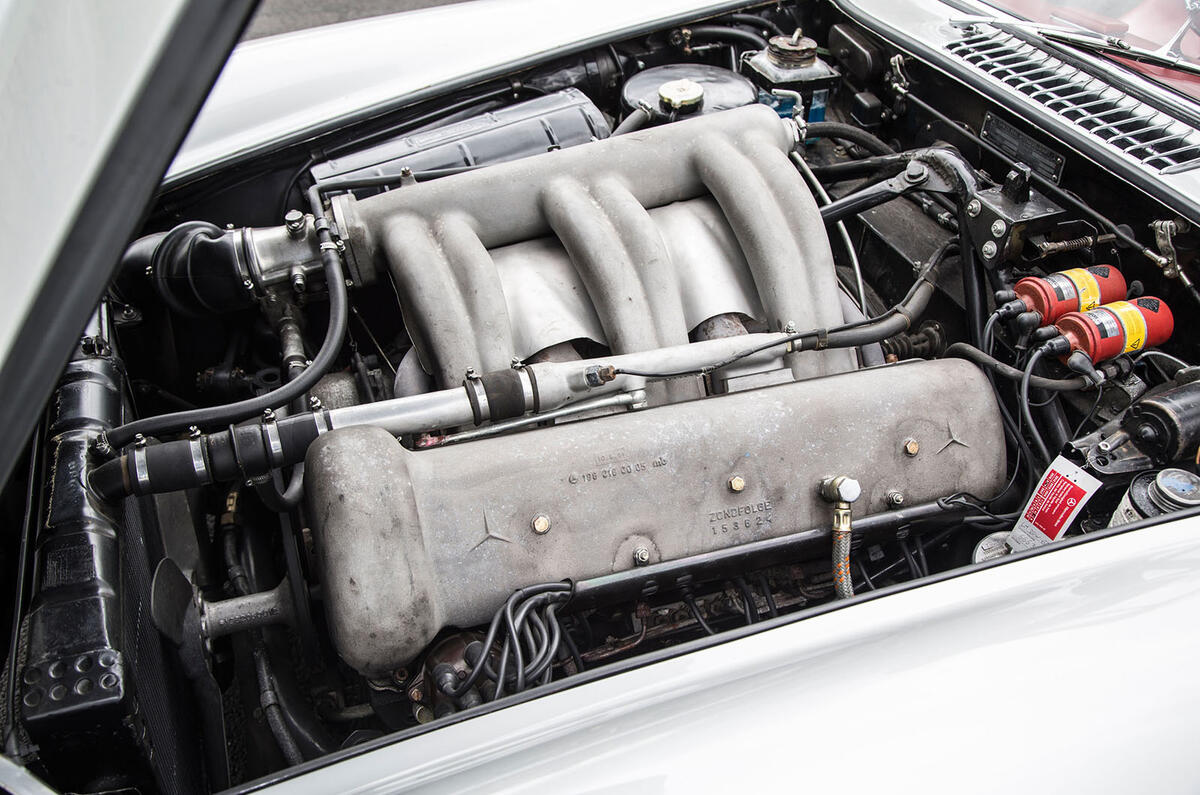

But my sense is that the car with the best claim to being the first true supercar is Mercedes-Benz’s 300SL ‘Gullwing’, an immaculate example of which you see photographed in company with its latest offering to the breed – the 63-years-younger Mercedes-AMG GT R.

So far as I am aware, the SL was the first to reset our understanding of what a road car could do. Even in 1954, there were some that could live with its performance, but these were racing cars capable of being driven on the road only thanks to regulations that required that ability. But although it did race, that was not the Gullwing’s purpose.

Indeed, being fundamentally designed for street use is as key a strand of supercar DNA as genuinely extraordinary performance for the standards of the day. Other top priorities include an appearance as arresting as it is exotic, an unaffordable price and the provision of pure driving pleasure. There are saloon cars, estates and even SUVs that have had supercar performance bestowed upon them, but this does not make them supercars any more than painting stripes on donkeys makes them tigers.

The GT R has more in common with the Gullwing than its frontengined, rear-drive, two-seat configuration and a three-pointed star on its nose. It has the correct supercar approach, too. Neither car is particularly practical, but nor are they so impractical as to be mere short-distance recreations, because that would tip them more towards being sports cars unless countered by simply unbelievable performance and presence. Both are cars you’d relish driving all day long. Both are sufficiently civilised on the motorway to make the journey to the mountains actually enjoyable rather than merely tolerable and both offer outstanding levels of entertainment when you finally arrive. Neither is intended or will be used primarily as a track car, but both – by the standards of their era – are entirely at home in that environment.

Join the debate

Add your comment

So Andrew thinks he should go

The title of the article

Not sure when the trend for wider and wider supercars began, maybe around the time of the Testarossa and Countach. It cant be Italians with their scenic narrow roads who prefer bigger and bigger supercars, their size must appeal to America and Middle East markets.

The World's Greatest Investment Cars - The Alternative Headline

Sad to read!

And this is the saddest thing about all of these super/hypercars - For far too many owners, it's more about the investment potential rather than owning and actually using an incredible car.

Most of the cars are bought and then spend almost their entire lives sitting in storage somewhere, rarely ever turning a wheel, especially the later super/hypercars like the P1, 918 and LaFerrari.

Too many owners daren't put any mileage on their cars due to the effect it would have on their re-sale value, and some owners buy the cars and never even register them so that their value remains as high as possible.

Considering how incredible these cars are said to be to drive (sadly, I doubt I'll ever have the opportunity to find out if they are great or not for Myself), that strikes Me as being a sad situation!