In a decade or two, we’ll all probably look back and laugh at the angst over EV battery size, weight and capacity, but for now, making improvements to all three is what everybody is hoping for. It’s beginning to look increasingly likely that those improvements won’t come from some massive breakthrough, such as a completely new type of so-far-undiscovered battery chemistry, but from an evolution of the lithium ion battery, which has taken more than 20 years to get from convincing prototypes to the stage it’s at now.

One aspect of lithium ion battery technology that arguably stands head and shoulders above the rest is weight. Reduce a vehicle’s weight and it needs less energy to take it a certain distance, whether it’s powered by electricity or conventional fuel. Make a battery lighter and the pressure comes off the chemistry and increasing energy capacity. But do both at the same time – increase capacity and reduce weight – and things are definitely looking up.

A research project by Stanford University and the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory has come up with a new cell design that is significantly lighter and less willing to catch fire and burn than existing technology. Reducing weight gives a twofold benefit. The energy density by weight is increased, so the size and weight of the battery can be reduced. That in turn reduces the overall weight of the car in a virtuous circle, so less energy is needed to move it.

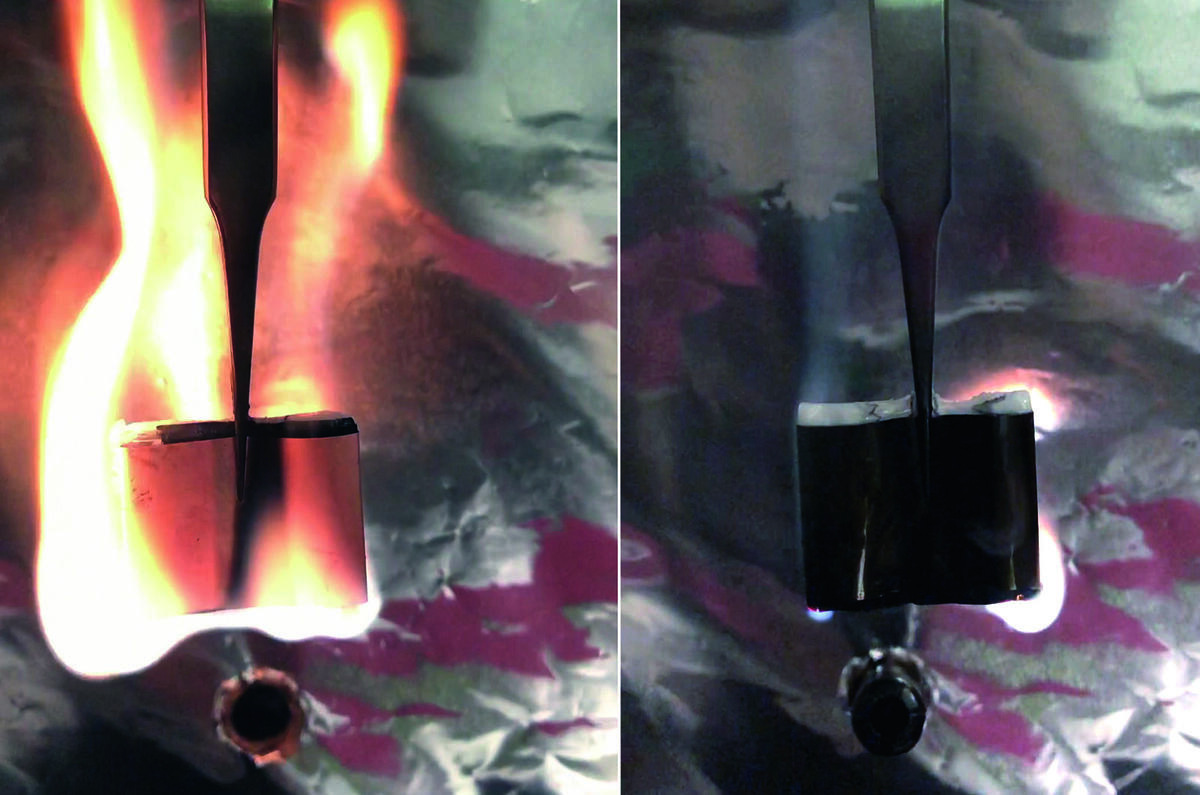

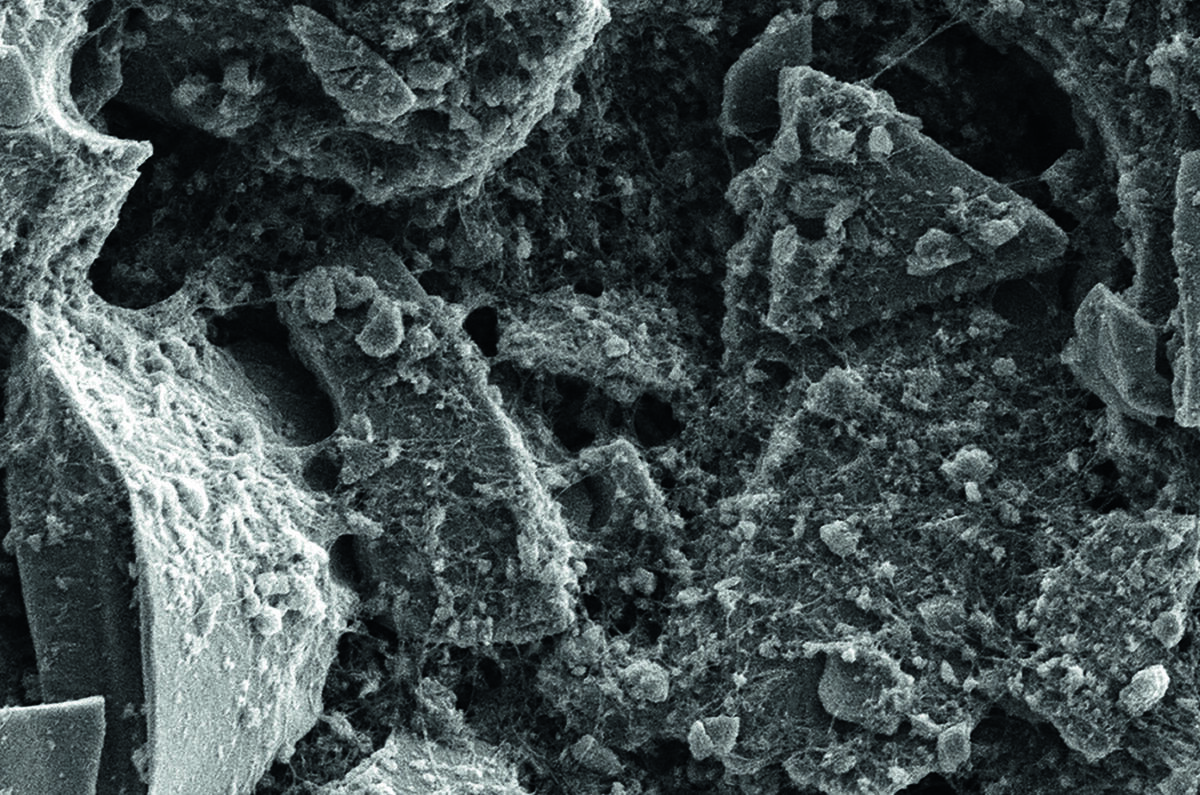

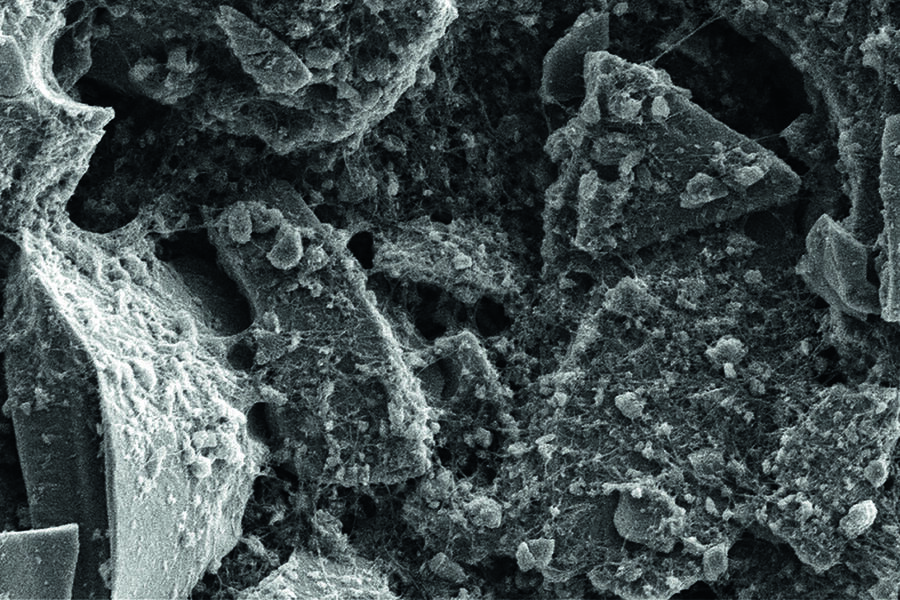

The secret lies in a new design of collector, a component of a lithium ion cell that carries the electricity to and from the electrodes (both the anode and cathode). Whatever the battery format, lithium ion cell collectors are made from copper foil and, although thin, are responsible for between 15% and 50% of the weight of a cell, depending on its size and thickness. Attempts in the industry to reduce the weight of collectors have so far been unsuccessful, but instead of solid copper the new collector is made from a polyimide, a polymer capable of withstanding high temperatures that has also been impregnated with a fire retardant.

The polymer is coated on each side (making a plastic sandwich) with an ultra-thin film of copper, so the finished item is not only lighter (by 80% compared with a conventional cell) but, unlike the conventional design, is also reluctant to burn. Normally, lithium ion cells burn easily until all the electrolyte has gone. Reducing the expensive copper content will cut the cost as well as the weight and there are environmental benefits, too, because huge amounts of the metal are used in anything electrical. Weight, cost and sustainability are also reasons why EV motor developers are researching the use of aluminium to replace copper in motor windings.

So far, the new technology has only been tested at the laboratory level but the signs are encouraging. It’s not expected that scaling up for mass production should present any problems and a patent has been applied for.

Join the debate

Add your comment

Not really a story.

Not really a story.

Batteries get better storage density by around 5% per annum but progress is lumpy.

They will need to demonstrate that this can be reliably manufactured at scale, that it works better than other solutions being worked on which do the same things and that it isn't incompatible with other improvements or existing chemistries for other elements of the battery.

Finally it has to be demonstrated to be worth the investment in new tooling and also that its improvements in density, safety and cost of materials don't come at the cost of something else like charging or discharging performance. None of these atrributes being a stationary goal both in state of the art or customer preference.

Batteries are a lot more complex than ICE where a new technology such as variable valves or direct injection is broadly applicable.

It is madness to bring this

It is madness to bring this forward a whole decade! The industry is not prepared for full-EV ranges and has been relying on hybrid technology being the interim solution, which was still supposed to be 'allowed'. Come 2030, the choice of new cars will be limited to those over £25,000 (inflation incl) leaving the budget-car segment empty and family cars limited to either second-hand EVs or short-range new cars. The only way of making EVs practicable for regular use is to include high-speed charging on every one, and to build up a high-speed charging network very quickly. Otherwise, people will be buying vast numbers of budget petrol or hybrid cars in 2029 and hoping they last a decade or two...

Not now

Buying an electric car now is NUTS. Battery technology is evolving so quickly that current electric cars will be the 'Stanley Steamers' of their day. Electric Motor technology is great, but batteries will change significantly over the next five years.

You could have said that 5

It's the same for any new

It's the same for any new technology - the first offerings are usually for those (mad?) people who will buy the latest technology regardless of cost. New technology will always be improved and made cheaper, often very quickly after it has first been commercialised. It didn't take Renault long to improve the battery on the Zoe. I'm still excited about how much batteries will develop, albeit incrementally from now on, such as in this article, and what place hydrogen fuel cells will have. I think they will exist side by side eventually with the latter taking care of the heavy stuff such as lorries and buses. However there are still organisations out there such as Riversimple backing the fuel cell for small cars, if the infrastructure is ever put into place.

It's the same for any new

It's the same for any new technology - the first offerings are usually for those (mad?) people who will buy the latest technology regardless of cost. New technology will always be improved and made cheaper, often very quickly after it has first been commercialised. It didn't take Renault long to improve the battery on the Zoe. I'm still excited about how much batteries will develop, albeit incrementally from now on, such as in this article, and what place hydrogen fuel cells will have. I think they will exist side by side eventually with the latter taking care of the heavy stuff such as lorries and buses. However there are still organisations out there such as Riversimple backing the fuel cell for small cars, if the infrastructure is ever put into place.

It's the same for any new

It's the same for any new technology - the first offerings are usually for those (mad?) people who will buy the latest technology regardless of cost. New technology will always be improved and made cheaper, often very quickly after it has first been commercialised. It didn't take Renault long to improve the battery on the Zoe. I'm still excited about how much batteries will develop, albeit incrementally from now on, such as in this article, and what place hydrogen fuel cells will have. I think they will exist side by side eventually with the latter taking care of the heavy stuff such as lorries and buses. However there are still organisations out there such as Riversimple backing the fuel cell for small cars, if the infrastructure is ever put into place.

Sorry about the x3 - I'm sure

Sorry about the x3 - I'm sure it's this website!