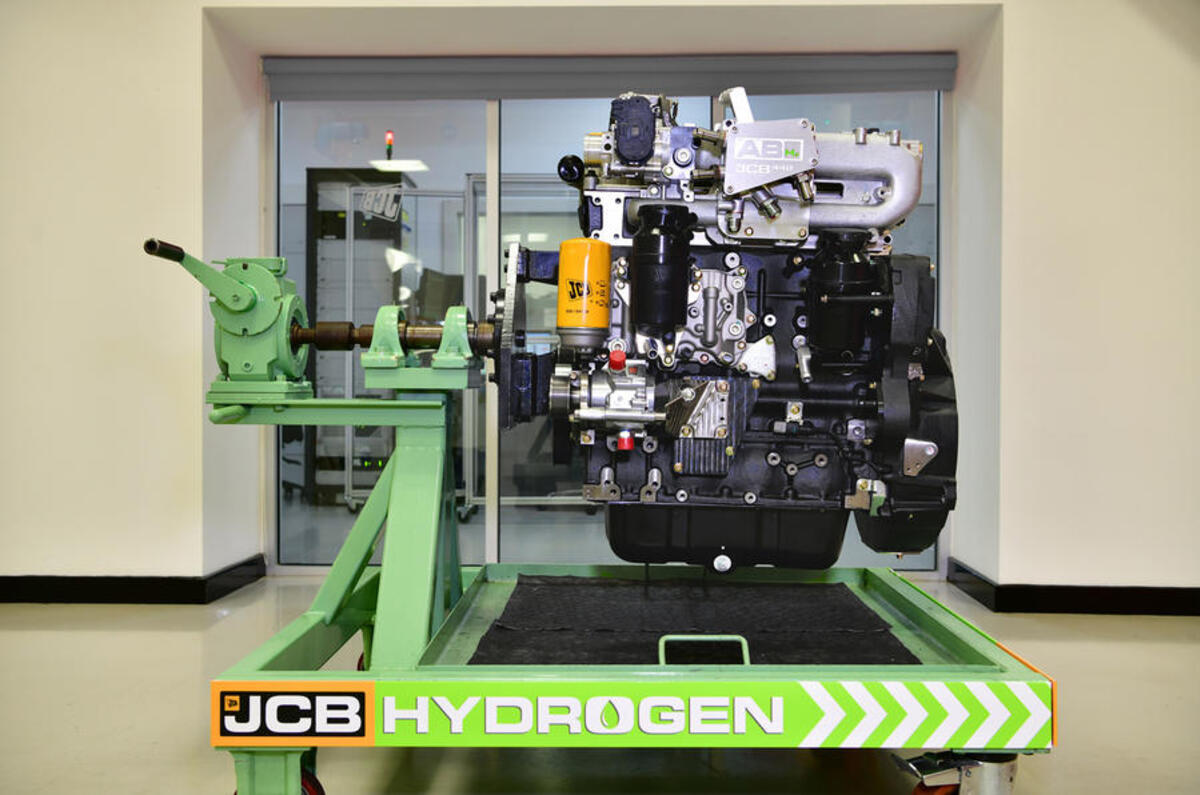

JCB has been awarded one of the RAC’s most prestigious awards for the development of its ABH2 hydrogen-fuelled engine.

The British company won the Dewar Trophy, which is presented in recognition of "an outstanding British technical achievement in the automotive field", for the third time.

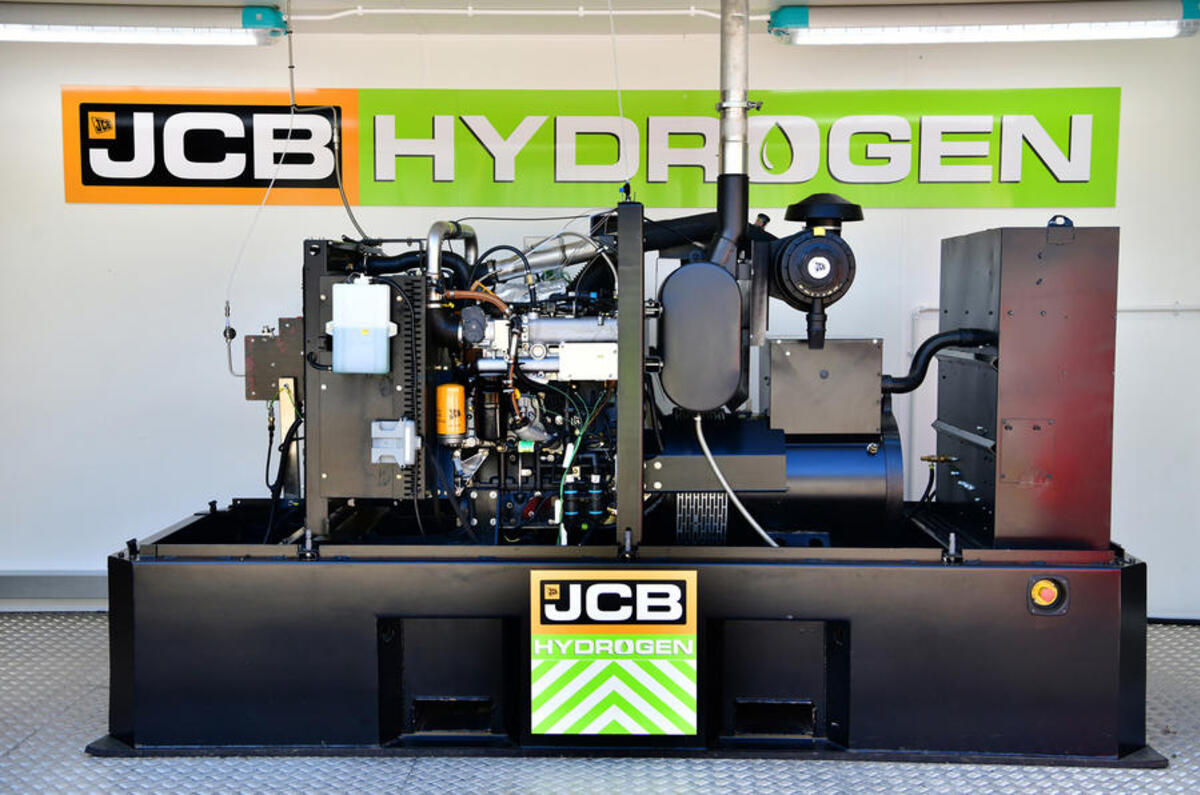

The hydrogen engine produces no CO2 emissions yet similar performance to the Dieselmax engine used in its existing machines. The only byproduct it produces is steam from a tailpipe.

"We’re extremely proud that the Royal Automobile Club has chosen to present JCB with the Dewar Trophy for the third time,” said JCB chairman Lord Bamford.

“We’ve invested heavily in alternatives to fossil fuels, including battery-electric and hydrogen fuel cells, but the fact that our hydrogen-fuelled piston engines can be put into production relatively quickly is something that’s vital in the current climate emergency.

"It’s an important and pioneering step towards a zero-carbon future and testament to the amazing abilities of our British engineers."

JCB revealed a prototype backhoe loader earlier this year equipped with an all-new induction system, with new pistons, lowered compression and port high-pressure common-rail fuelling. It produced less NOx emissions than a diesel, even after diesel aftertreatment that cut pollutants by 98%.

A newly updated prototype for a Loadall telescopic handler was presented in October 2021 in the company of UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson.

JCB looks set to invest £100 million into the project, with hopes of recruiting 50 extra engineers to deliver the first hydrogen-powered machines to customers by the end of 2022.

The company was first awarded the Dewar Trophy back in 2007 for achieving a diesel-powered land-speed record, hitting 350.092mph at the Bonneville Salt Flats, and won it again in 2019 for the development and introduction of its 19C-1E electric mini excavator.

Join the debate

Add your comment

Gagaga is absolutely right in his criticism. Using hydrogen in a fuel cell to generate electricity does at least produce no tailpipe emissions - the JCB approach will inevitably produce oxides of nitrogen, even if no CO2. But of course, the likelihood is the production of the hydrogen will generate CO2. The carbon emission is just moved from tailpipe to factory - which applies equally to fuel cells.

Yes, it is possible to produce green hydrogen (by electrolysis) but for road transport it's a very inefficient way of making use of electricity from renewable sources. For a very long time to come far better to use all the green hydrogen in such as industrial processes such as steel making.

It's also worth asking the question about how and where JCB envisage refuelling of all these vehicles? Diesel is pretty easy, and able to be done with very simple pumps - even pouring from a can for small scale use. Hydrogen? Storage realistically involves big and heavy pressure containers, whose weight is many times that of the fuel they contain, and "refuelling" involves a compressor operating at extremely high pressure. It's all *possible* of course, but foolish to gloss over the difficulties.

Likewise transport from manufacture to site. Like for like, many times (about 10-15) more tanker deliveries are needed for hydrogen versus diesel - it's all due to the ratio of pressure vessel versus fuel weight, and tanker total payload. The more you look into the subject of hydrogen for road vehicles, the more silly it gets. For cars, hydrogen (with fuel cells) was seen 20 years ago as the only alternative for cleaning emissions. What's changed there is the huge and fast progress in battery technology - energy density, charging speeds, and (most importantly) cost - and now hydrogen has simply been left behind in that field.

OK, batteries may be more problematic for typical JCB type uses, but as you ask "what would you suggest", I'd be inclined to look more towards biofuels and other synthetic (liquid) fuels where battery is not currently suitable. I'm afraid this suggestion from JCB smacks very heavily of greenwashing, especially if they're not even going the fuel cell route, and may be doomed to failure.

Zero emissions? Well, apart from those used to produce/transport/store the hydrogen, and (presumably) NOx and other stuff resulting from burning stuff in air at high temperature and pressure?