Although alternatively fuelled vehicles (AFVs) seem modern, the technology they employ is, in fact, ancient.

‘The death of the internal combustion engine’ is a topic that has been discussed within the automotive industry since its very inception, but, until very recently, that discussion may as well have been held in an echo chamber.

Now, nearly every major manufacturer is being proactive with replacing petrol and diesel, and significant sales growth is coming in.

But it has taken a while. If you were to order AFVs by their current likelihood of becoming the future of mainstream personal transport, I would argue the resulting list would go something like this: Electric batteries, hydrogen fuel cells, hybrids, plug-in hybrids (PHEVs), biofuel, compressed natural gas (CNG).

However:

CNG has been used to fuel vehicles since as early as the 1930s; the first ethanol (biofuel) engine was built in 1824, and the Ford Model T (1908) could use it, gasoline, or a mixture of both; Porsche built the Mixte PHEV in 1899; The Armstrong Phaeton of 1896 had a petrol engine connected to a dynamo flywheel, which charged a battery; one of the world’s first internal combustion engines, the de Rivaz of 1807, was hydrogen-powered, and that was applied to a car a year later; and experimentation with electric cars dates back to the early 1800s, with experimental electric cars appearing as early as 1867.

Back on 15 June 1967, we here at Autocar were having the very same thoughts about the future of automotive propulsion, although at a time when AFVs were markedly less prevalent, and we envisaged Wankel petrol engines, gas turbines or steam engines to be future possibilities.

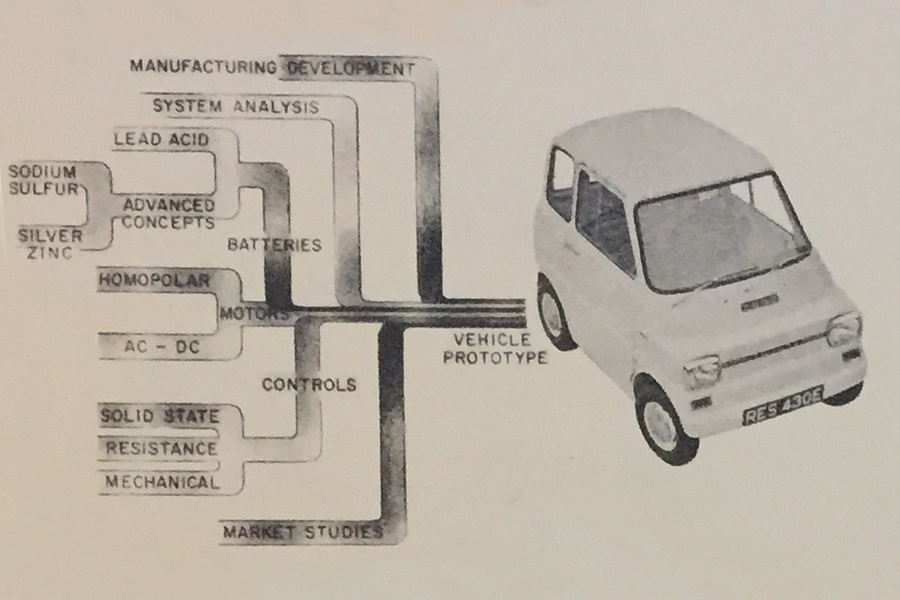

“The car engine of the 1990s may not yet have been conceived,” we said. Well, it’s 2017, and we’re still waiting for something else, so it looks (for now) like electricity will be the one – as it did back then, as we took a view on Ford’s tiny electric Comuta prototype, “a practical vehicle of limited performance, designed for restricted use in cities, rather as electric golf buggies are used around a particular golf course”.

A box on wheels little bigger just half the size of a Ford Cortina, yet in which four people could just about squeeze, the Comuta was powered by four 12v 18amp lead batteries, which gave a range of 37 miles and a top speed of 37mph. Just like a milk float (of which there were nearly 50,000 in the UK by 1970).

Add your comment