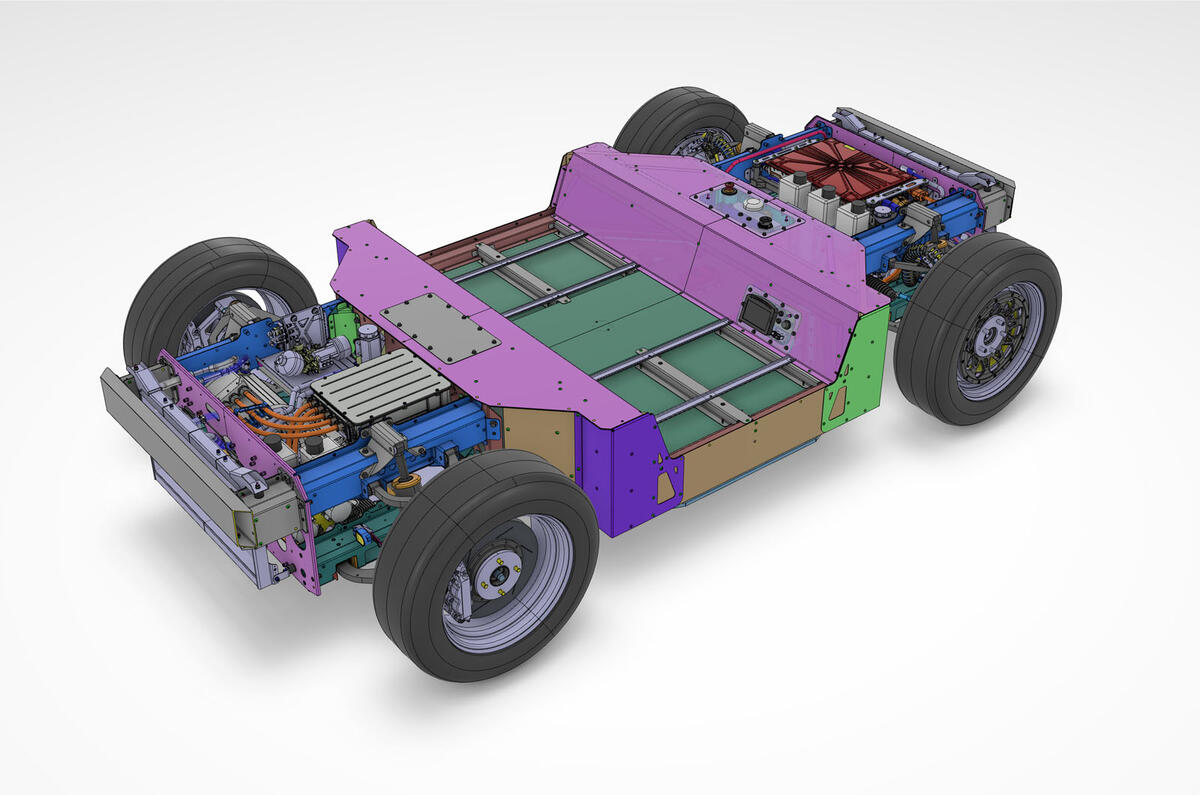

In the beginning – which is to say in September last year – Delta Motorsport’s highly flexible new S2 autonomous and electric car chassis, one of the star exhibits of this year’s LCV Show, was only going to appear as a notional prototype, born in a computer and destined to stay there forever.

Under the original plans, this all-aluminium, skateboard-style EV chassis design – which now sits proudly in three dimensions at the centre of a specially designed stand – wasn’t even due to show its screen-based face until this time next year.

Then everything changed. In a remarkable last-minute turnaround, Delta’s two founders – engineering director Nick Carpenter and operations director Simon Dowson – decided their S2 project would be more timely and have a far bigger impact if shown this year as a live concept. As project leaders they hurriedly consulted partners in this Innovate UK-backed project – Titan (by-wire steering), Alcon (by-wire brakes), Warwick Manufacturing Group, Potenza Technology (digital safety know-how), Cranfield University (limit handling studies) – and, with everyone’s enthusiastic approval, and working alongside GCE (structure design) and Tecosim (CAE specialists), they set to work at top speed.

The chassis you see here was completed just days before the show opened. It was a true feat of execution, although Carpenter, Dowson and partners seem entirely unfazed by their achievement. It goes with the territory in their high-pressure world of technical creativity. “Being part of a small organisation with a limited budget is a really positive thing,” Carpenter explains. “The bigger you are, the more prone you are to paralysis by analysis. There’s huge pressure to find exact answers when there may not be any. In a small company, you just don’t have time.”

Join the debate

Add your comment

3, 2, 1...

Here comes outrage from the below the fold reactionaries...

It’s alright boys, you’ll still be able to play with your toys.